[Review] It Follows

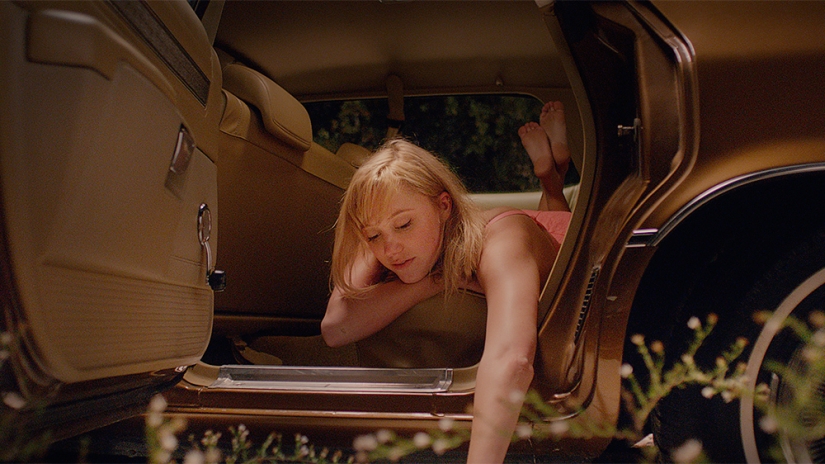

It Follows belongs in the pantheon of great suburban horror films like Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street. It's an impeccably crafted movie that haunts as much as it unnerves. What lingers isn't just the paranoia established from the outset or the constant sense that our heroes' lives are in danger, but something far more thoughtful.

Writer/director David Robert Mitchell uses 1980s genre tropes to examine teenagers as the cusp of adulthood. Many of the characters are obsessed with becoming adults or at least appearing mature, and yet they're also afraid to leave the comforts of youth and suburbia. To dig deeper into this material, Mitchell does advanced math with one of the most simple horror movie equations: "sex = death".

[youtube id="9tyMi1Hn32I"]

It Follows

Director: David Robert Mitchell

Rating: R

Release Date: March 13, 2015

Jay (Maika Monroe) hooks up with a guy named Hugh (Jake Weary), which wasn't such a good idea since he's the latest link in a chain of doomed sex partners. After having sex, the most recent partner becomes stalked by a supernatural presence that shambles mutely forward. Think a zombie or Michael Myers from Halloween. If the presence catches up with you, you die, and the previous sex partner is stalked next. All you can do is pass it on; sex is a kind of transmittable death sentence.

It sounds silly on the surface, and this sort of set-up might lead to exploitation territory in other hands, but Mitchell focuses on the characters and how the immanent threat of dying enters their sheltered lives. Like Jennifer Kent's The Babadook, It Follows is concerned with emotional stakes rather than just cheap scares, which is thanks to both the screenplay and the cast. By getting the audience to invest in this group of teenage friends and care about Jay's well-being, the horror is more palpable.

In slasher movies, sex usually signified a sin that needs to be punished or the horrible repercussions of pleasure, but there's more to sex in It Follows. Sex is both a rite of passage into adulthood and a kind of memento mori. In this film, "sex = death" is not a puritanical equation about the virtues or pragmatism of teenage virginity, but rather an acknowledgment about the inevitability of both sex and death in everyone's lives. Sex, like death and like the presence that's after Jay, is an unstoppable force.

All the rich metaphorical material would be mere garnish if Mitchell hadn't made a film that's so well put together. It Follows is shot with care, augmented by its original synthesizer score (a la classic John Carpenter) and the menacing sound design. In the opening shot of the film, we're given an extended take from a fixed spot on the street of a suburban neighborhood, panning to catch someone helpless and possibly insane. Something's not right in the world we've entered, which defies being pinned to a specific era, and we never exit this timeless, dreamlike state. That opening shot creates a space to deal with the idea of teenagehood, and it also lets the audience know that the adults can't help their children anymore. This confrontation with death is something their kids have to handle on their own.

So many of the images in It Follows are beautiful to look at given the way cinematographer Mike Gioulakis plays with color, movement, and negative space to emphasize the underlying emotions of each scene. Clayton Perry, Christian Dwiggins, and Lauren Robinson of the sound department also deserve high praise, foregrounding the dread even before the film's first shot. It Follows is a great reminder of how effective the most basic formal elements of a movie can be when every choice has a clear sense of purpose.

A bunch of horror and science fiction films of the last decade have tried to get by as successful pastiche and nothing more, as if recreating the past is sufficient. It's usually not. Most people can restate what's already been said, but what gives a work a life of its own is when someone says something original or reconsiders what's been said from different angles. It Follows is brimming with that sense of vitality, which makes everything it says about dying surprisingly potent.

[Review] My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn

"Art is hard." That's the underlying thesis of most documentaries about making movies. The truism is present throughout My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, a one-hour documentary shot by Refn's wife, Liv Corfixen, while he was making Only God Forgives. Refn seems perpetually distraught as he's writing and directing his follow-up to Drive. He spends multiple scenes in his lavish 42nd-floor Bangkok hotel room sulking on the couch, depressed in bed, or pensively looking out the window at the world below. What's on screen is just a snippet of the woe. Cofixen complains behind the camera that Refn doesn't allow her to film when a major crisis occurs.

There seem to be two other threads running through the documentary that are intertwined with the idea that art is hard: "success is damning" and "failure is inevitable." My Life Directed by Nicolas Windin Refn is about how artists interpret failure and the sense that they're failing. How fascinating you find the film depends on how closely you follow Refn's work and your patience for the banal.

[iframe id="https://www.youtube.com/embed/6Rz9SAZQrH0" align="center" mode="normal" autoplay="no" maxwidth="825"]

My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn

Director: Liv Corfixen

Rating: PG-13

Release Date: February 27, 2015

My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn is only kind-of about the making of Only God Forgives. The primary focus is Refn's artistic struggle in mundane settings—hotel rooms, cabs, before screenings—rather than on set. The film opens with Refn so anxious about making a new movie that he asks his hero and friend, legendary cult filmmaker Alejandro Jodorwosky, to do a tarot card reading for him. Maybe the narrative symbolism of the cards will ease Refn's superstitious mind. Candor thrives in these unassuming places. Refn's no longer forced to play leader for a crew and can let his guard down, or at least maintain a haggard-yet-guarded front for Corfixen's camera. When a camera's involved, intimate disclosures only go so far, even if you're married.

Ryan Gosling appears in a few of these off-set sequences. The eye gravitates toward him—star power in action. These scenes with Gosling have a sly, jokey, almost mockumentary feel, which makes them especially entertaining. While Refn explains his ideas about the similarities between violence and sex, Gosling smirks at the camera like Jim from The Office. I wouldn't mind a mini-series starring Refn and Gosling together on the road, sort of like Michael Winterbottom's The Trip with Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon.

Despite a few enjoyable scenes, My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn is only semi-interesting. Even at just an hour long, the material is thin and superficial, less a crafted non-fiction narrative and more a home movie. At worst, it's a glorified featurette for the Only God Forgives Blu-ray. Even fans of Refn might shrug the documentary off. If you aren't familiar with Refn's work or Only God Forgives, you might wonder why that man in a beautiful hotel is so depressed.

Refn comes across too worried and too self-absorbed for the film to be self-congratulatory, and so the documentary avoids becoming a complete vanity project. Yet there's a sense of self-importance that's unwarranted. Only God Forgives may have been low-budget, but apart from the usual on-set challenges, nothing seemed especially noteworthy. Sure, it's Refn's big critical and commercial failure, but he bounces back from it unscathed.

Toward the end, Refn complains that he's wasted six months of his family's life. Consider the Herculean struggles in other documentaries about making movies, such asThe Burden of Dreams, Hearts of Darkness, or Lost in La Mancha. By comparison, Refn's problems, while legitimate and disheartening, seem like temporary frustrations rather than existential struggles for authenticity or the difference between subsistence and going hungry. As the documentary shows, Refn's problems are nothing that a good sulk won't fix.

Jon Stewart Is Leaving The Daily Show After Changing Late Night In the 21st Century

As a kid I sometimes stayed up late to watch the first 15 minutes of Johnny Carson even though I was too young to get the jokes. When Carson left The Tonight Show, I remember adults expressing fondness for him, but Carson as a cultural phenomenon was something I was too young to feel attached to. David Letterman, whose last show is in May, I'm more on board with, but even still, there's a sense of a generational divide, like I missed that train by a decade.

That's not the case with Jon Stewart. We go way back. I was at least aware of Stewart as a TV personality in the early 90s thanks to the short-lived MTV show You Wrote It, You Watch It (the phrase "fish butt" still makes me giggle) and the more successful Jon Stewart Show. As for The Daily Show, I've watched it pretty regularly it since the Craig Kilborn days (which introduced me to the cult masterpiece Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky), but it was Stewart who gave the program a political edge and a moral imperative. That sense of purpose transformed The Daily Show into its own vital late-night entity, one that's as been as important and influential as Late Night with David Letterman and the revamped Saturday Night Live of the late 80s.

With Letterman and Stewart leaving their shows this year, the whole face of late-night programming will change for Boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials. But we knew Letterman's exit was coming for a while. Stewart's unexpected announcement yesterday made me especially wistful when it came to my formative late-night memories.

[iframe id="http://media.mtvnservices.com/embed/mgid:arc:video:thedailyshow.com:2595200c-c1a0-4549-9c18-bf98644bac18" align="center" mode="normal" autoplay="no" maxwidth="825"]

Stewart isn't retiring from the public eye as far as anyone knows, but the collective shock was enough to render Brian Williams' half-year suspension from NBC an also-ran headline. It's a testament to how much The Daily Show has become a comedy institution that's also more trusted than news itself. Comparisons to Letterman and SNL are warranted. The Daily Show is its own irreverent beast, and it's catapulted multiple careers while changing what late night could be for the the 21st century.

Yet The Daily Show is synonymous with Stewart, which is common when a host puts a stamp on a show. Even as correspondents left to start their own careers—Stephen Colbert, fittingly, to carry the torch from Letterman; John Oliver, also fittingly, to carry The Daily Show's torch in the form of Last Week Tonight—Stewart remained the program's lovably impish center. Viewers could count on him to be honest whether expressing heartbreak, moral outrage, mocking incredulity, or even just confused resignation. Seeing his face so often in the same late-night slot consistently calling out lies and misinformation is what led to Stewart, as much as he hated it, becoming the most trusted name in news. (Walter Cronkite by way of Ernie Kovacs.)

There was speculation that NBC had courted Stewart to host Meet the Press. Nevermind that Stewart's style is too combative for Meet the Press, a program that, like other Sunday morning political shows, functions as a safe zone for politicians to deliver talking points without actually being held accountable—this was true even when Tim Russert was moderator, let's not kid ourselves.

And yet Stewart moderating a political show sort of made sense. Following Russert's death in 2008, Senator Joe Lieberman called Russert the "Explainer in Chief of our political life." For many Gen Xers and Millennials, Jon Stewart was their Explainer in Chief.

The television I loved and that proved so influential to me had that "Explainer In Chief" quality. My understanding of adult life has been molded by or linked to late-night comedy. (This is something I'll probably need to explain to a therapist someday.)

One of the first non-kid books I remember buying was a collection of Letterman top 10 lists. Re-runs of early Letterman were on the E! channel, and SNL's 80s Renaissance was ongoing and also being re-run on Comedy Central (for a while, the original cast in truncated form could also be seen on Nick at Night). Throughout high school, I'd stay up to watch Conan O'Brien. On the verge of being canceled for months, Conan's show in those wild and woolly days featured dancing/farting hot dogs, a 1950s robot dressed as a 1970s pimp, and staring contests chock full of dadaist sight gags. The Daily Show became political when I turned 18, and while I was at least semi-aware of political conversations via Bill Maher's Politically Incorrect, the kinds of concerns and forms of critique and discourse on The Daily Show would prove more influential to my political views as an adult.

In some ways, I grew up on Late Night with Conan O'Brien, but I came of age with The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.

Growing up and getting older with someone on TV is such a strange thing. Even though Stewart's still hosting and the show will continue without him, I caught myself thinking of The Daily Show in the past tense a few times while writing this piece, like an era had already ended simply because I knew it was going to end.

There's going to be a long goodbye to Stewart in the coming months and loads more writing about The Daily Show's place in the late-night canon, not to mention its influence on a new generation of comedians, satirists, media critics, and journalists. There's the odd excitement (tinged with fear) of change and how the new host of The Daily Show will put his or her stamp on the program. The guest list should get more interesting, and I sense Stewart's impending departure may even prompt Senator John McCain to return to The Daily Show for the first time since 2008.

And there are all those questions about why Stewart's going and what's next. Maybe more filmmaking, maybe a political run (like late-night comedy alumnus Al Franken?), maybe a new show with a different format. Maybe, as he alluded to on last night's show, Jon Stewart just wants to watch his own children grow up and become adults.

I miss him already.

[Review] Amira & Sam

There might be a more interesting film in Amira & Sam, the feature-film debut from writer/director Sean Mullin. I say that because there's the set-up for a fine misfit love story here. Sam (Martin Starr) is an Iraq war vet awkwardly trying to assimilate back into civilian life, Amira (Dina Shihabi) hocks bootleg DVDs of romcoms and has to go into hiding to dodge the law. And, of course, the couple hate each other at first.

Amira & Sam

Director: Sean Mullin

Rating: N/A

Release Date: January 30, 2015

In the best misfit love stories (e.g., Minnie and Moskowitz, Harold and Maude, Punch-Drunk Love), there's a sense that we're watching two oddballs against a world that wants them to conform, and Sam and Amira make a fine pair of misfits. They're economic, social, cultural, and political outsiders, two lost souls in New York living in the outer boroughs; for Sam, it's outermost Staten Island. During one scene in which the pair try to figure out who's sleeping on the floor and who's taking the bed, Starr and Shihabi share such a flirty warmth and natural charm. The apartment's too small to put up the Walls of Jericho a la It Happened One Night, so the awkward situation forces closeness, and both Sam and Amira counteract the awkwardness by giving in to their proximity.

Yet despite the kookiness of the misfits, Amira & Sam can't overcome its writing, which forces our heroes and their lives into narrative conformity. The film feels pressed into the mold of other formulaic romcoms, with the story beats, the cliches, and the obviousness conquering the film's more unique charms. The misfits are demisfitted.

Mullin includes some potent (albeit heavy handed) political material regarding veterans in civilian life. While Sam hasn't suffered any physical or psychological trauma, he seems alienated, which may have more to do with Starr's deadpan performance. Sam's cousin, Charlie (Paul Wesley), runs a hedge fund and thinks of Sam's service more like a resume item and a way to lure in investors rather than an actual experience with existential repercussions. Income inequality plays into this part of the story, with Sam having to make choices that may compromise his character despite the financial advantages. It's the haves exploiting the have-nots and the have-nots sacrificing their lives so that the haves can be unrepentant douchebags. Perhaps anachronistically (the film takes place in 2008, three years before Occupy), Mullin includes mentions of the 1% in his screenplay to hammer the points even further.

While Sam's outsiderness is given a kind of roundness through bland aspirations and an upstanding moral code, Amira feels thin as a character. The film is more Sam's and he has more agency, and I can easily recount his internal life. But beyond a kind of spunkiness, rebellion, and general listlessness, I couldn't really grasp the hopes and dreams that Amira might have, or what she might have wanted, or how these aspirations became waylaid, or even why she finds such a connection to romcoms. It's nothing against Shihabi since she has an ease on screen, but more about Amira seeming like an accessory to Sam's story who's along for the ride rather than a character fully considered. There's the hint of fascinating cultural contradiction about her since she wears a revealing outfit with a hijab, and yet it's never explored beyond off-hand remarks by side characters.

At one point of Amira & Sam, the couple sits by the Verrazano Bridge, like a callback to Woody Allen and Diane Keaton at the Queensboro Bridge in Manhattan. Maybe Amira recognizes the film reference, but she didn't say anything. Maybe she recognized that from that point on, their lives were starting to become a less interesting sort of romance. I wish she'd said something and done something about it.

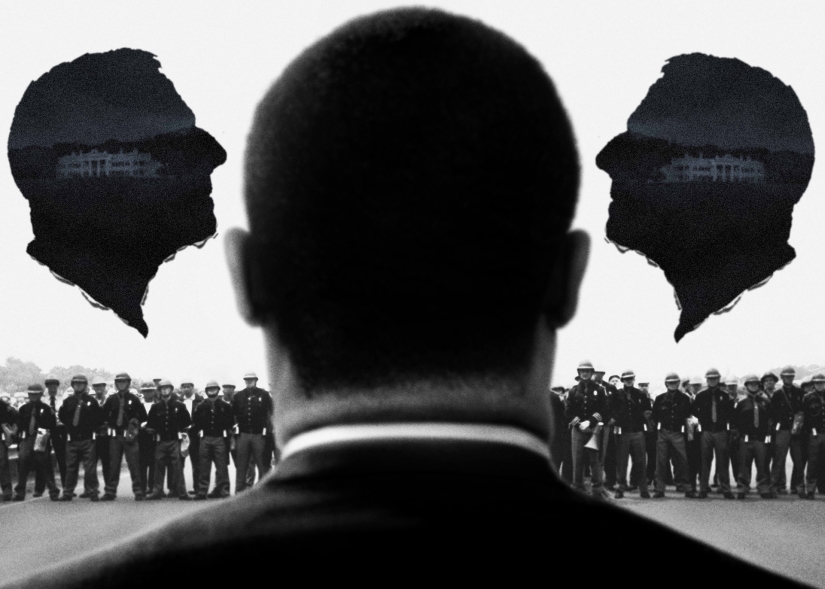

Selma's Oscar Snub: Why Awards Strategies and Hollywood Politics Are a More Likely Factor Than Gender and Race

As with every year, the big story following the announcement of the Academy Awards nominations is who got snubbed. This year, the most glaring omission was Selma.

The critically acclaimed film about the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches snagged two Oscar nominations: Best Picture and Best Original Song ("Glory" by John Legend and Common). But nothing for Selma's director Ava DuVernay, or its star David Oyelowo, or cinematographer Roger Deakins, or screenwriter Paul Webb.

The optics of the snub are bad. As The Hollywood Reporter noted yesterday, the field of nominees for the major awards is predominantly white (and exclusively white in the acting categories). It's left a number of people wondering if racism and/or sexism was involved with Selma's snub, or if the controversies involving Selma's depiction of President Lyndon Johnson were also a factor.

After exchanging emails with my friend Steve Kopian who runs Unseen Films, I think there's something else going on even though race and gender are important to consider. It seems like the main reason Selma was snubbed had to do with its late release and poor awards season campaign, because in the end, the Academy Awards are a PR battle.

Selma was delivered to Paramount on November 26, which left limited time to get a robust award's season strategy in motion. Given that, the main factors that led to the Selma snubs are probably the following:

- DVD screeners for Selma were only sent to Oscar and BAFTA voters; none were sent to voters of the Directors Guild of America (DGA), the Screen Actors Guild (SGA), the Producers Guild of America (PGA)

- Selma didn't have a world premiere at one of the major year-end film festivals (i.e., the Toronto International Film Festival, the Telluride Film Festival, the New York Film Festival)

- Selma's limited Christmas release in select markets came too late to build the necessary Academy voter buzz

Earlier this week, Variety had a good rundown of the importance that DVD screeners played in all this. There's the possibility that major industry players didn't get their eyes on the film in time, or that they saw the film too late to change their minds about other films they saw earlier.

Production of official watermarked DVD screeners takes a while. Since the film was delivered late in November, the screener DVDs weren't even ready to go to voters until December 18. By then, SAG's voting period had passed and the PGA voting period was in full swing. Buzz and chatter back and forth between different groups of voters just wasn't there, so no chance for little suggestions of award buzz being transferred from one set of industry voters to the next.

Sadly, despite the gambit, Selma wasn't nominated for any BAFTAs.

Had Selma been completed earlier, some of this industry buzz could have been generated sooner at one of the major last-quarter film festivals. A movie can be elevated in the eyes of the industry simply by a major debut at a film festival, and it can help a movie in a unique way that a high-90s Tomatometer score can't.

Since Selma was completed in late November, there was no chance that a satisfying version of the movie would be ready to play at Telluride or Toronto (both take place in September) or at the New York Film Festival (which takes place in October).

A working version of Selma played at the AFI Fest on November 11, two weeks before the final version of the movie was delivered. While the early buzz at AFI Fest was positive, again, it may have been too late to knock out earlier award season frontrunners, like Richard Linklater's Boyhood (which debuted at Sundance), Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel (which debuted at the Berlin International Film Festival), Bennett Miller's Foxcatcher (which debuted at Cannes), Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's Birdman (which debuted at the Venice International Film Festival), and Morten Tyldum's The Imitation Game (which debuted at the Telluride Film Festival).

Of course, Clint Eastwood's American Sniper also played at AFI Fest, and despite the controversies around that film's factual errors, it garnered six Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Adapted Screenplay. So what gives there? In terms of award season, I think there's a unique case of Eastwood's clout making a big difference, because clout goes a long way in the Oscar PR battle.

Eastwood's an esteemed fixture in Hollywood given the longevity of his career. A late release by Eastwood has a better chance of crashing the awards season than a late release by someone new in the eyes of Hollywood like DuVernay. Had Selma been released by The Weinstein Company rather than Paramount, perhaps Harvey Weinstein would have glad-handed it into the major awards somehow. That's the power of clout.

But after the behind-the-scenes industry stuff, we're left with the nominations themselves and a look at how they reflect or are interpreted through the lens of real-world politics regarding race and gender. And I can't deny it looks bad.

The Selma snub seems especially egregious since this year's nominees play into a particular and persistent narrative about the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS): they are a bunch of out-of-touch old white men. In fact, the Academy voters are 93% white, 76% male, and their average age is 63. (These stats come from a report by NPR from February last year.) Current AMPAS President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, an African-American woman, is pushing for diversity in AMPAS membership, but the push will take time.

The disappointment in this year's Selma snub—maybe in most awards snubs, regardless of the medium—comes back to a narrative of blandness and the taste of the status quo getting reaffirmed, namely that the safest and least challenging works tend to be the ones that win; or in large groups of voters, it's the consensus winner that gets the award even though voters felt more passionate about another set of works. (First is the worst, second's the best, third is the nerd with the hairy chest, but fourth gets the award this year because it's all right enough probably I guess.)

I don't know if blandness is necessarily the case this year, though, given the strength of several of the movies that have been nominated for Oscars. But it's weird to think that a movie like Selma might have fared much better at next year's Academy Awards, given a whole 12 months to roll out a well-planned campaign rather than just one rushed and chaotic month. If Selma debuted at the Sundance Film Festival later this month or at Berlin in February, and if it rode that acclaim through 2015... but even then, who's to say?

Based on a True Story: Foxcatcher, Selma, and the Controversy of Adapting Real Life

Last week, Olympic wrestler Mark Schultz took to Twitter and Facebook to lash out at filmmaker Bennett Miller. Schultz is one of the subjects portrayed in Miller's latest film, Foxcatcher, which stars Channing Tatum, Steve Carell, and Mark Ruffalo. Adam B. Vary at Buzzfeed has cached Schultz's posts, which have been deleted from his social media accounts. "YOU THINK I'M GOING TO SIT BACK AND WATCH YOU DESTROY MY NAME AND REPUTATION I SWEAT BLOOD FOR," one tweet reads. "YOU AINT' SEEN NOTHING YET DUDE."

Foxcatcher focuses on the relationship that multi-millionaire John du Pont (played by Carell) developed with Schultz (played by Tatum) when establishing a wrestling training camp on the du Pont estate. Though never stated overtly, it's implied that du Pont is sexually attracted to Schultz. Miller—whose previous films, Moneyball and Capote, were also based on true stories—plays with the imagery and cliches associated with this awkward sexual dynamic. Hunky house guest Tatum is down on the mat with the effete yet maybe-too-enthusiastic Carell. In one sequence, Du Pont gets Schultz hooked on coke, and Schultz neglects training in a haze. Time passes off camera, the audience fills in the blanks. The next scene we see Schultz's character, he's upset and coked out and drunk, his hair bleached a cute California-dude blond.

On Facebook, Schultz called this implication of sexual relationship "a sickening and insulting lie" that jeopardized his legacy.

The Foxcatcher flare up and ongoing controversy surrounding the depiction of President Lyndon Johnson in Ava DuVernay's Selma got me thinking about the challenges that go into turning real life events into films. When fiction is based on a true story, the notion of true may have less to do with the facts and more to do with a contour of history and a shape of narrative. The phrase to emphasize is sometimes "based on" rather than "true story," though "true" is tricky too.

[youtube id="x6t7vVTxaic" align="center" mode="normal" autoplay="no" maxwidth="829"]

For Selma, the controversy stemmed from two guest columns by stewards of President Johnson's legacy. The first was "What Selma Gets Wrong" by Mark K. Updegrove on Politico, published just days before Selma's limited Christmas release. Updegrove is director of the L.B.J. Presidential Library and Museum and author of a book on the late president called Indomitable Will. The primary focus of Updegrove's piece is the portrayal of Johnson (played by Tom Wilkinson) as an impediment to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (played by David Oyelowo) rather than a clear partner in the Civil Rights Movement. Updegrove presents Johnson's political priorities in terms of pragmatism, and that the later passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 as a strategic delayed move that allowed the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Updegrove writes, "At a time when racial tension is once again high, from Ferguson to Brooklyn, it does no good to bastardize one of the most hallowed chapters in the Civil Rights Movement by suggesting that the President himself stood in the way of progress."

Published the day after Christmas, Joseph A. Califano, Jr.'s piece in The Washington Post, "The Movie Selma Has a Glaring Flaw," added to the scrutiny. Califano was President Johnson's top assistant for domestic affairs from 1965 to 1969, and the crux of his piece, like Updegrove's, is that Johnson and King were partners rather than uneasy allies. It should be noted that Califano's own flaw in his chain of argument comes early when he writes that the Selma march was Johnson's idea all along. Regardless, he raises interesting points about the disjunction between the history he feels intimately familiar with and the way certain events are depicted in the film.

"All this material was publicly available to the producers, the writer of the screenplay, and the director of this film," Califano writes. "Why didn’t they use it? Did they feel no obligation to check the facts? Did they consider themselves free to fill the screen with falsehoods, immune from any responsibility to the dead, just because they thought it made for a better story?"

Maybe. But it's also more complicated than that.

[youtube id="8361stZ8n0w" align="center" mode="normal" autoplay="no" maxwidth="829"]

There's a large question of legacy in these separate grievances against Foxcatcher and Selma. Legacy can trump the messiness of real life and complexities of history because legacy refers to an enduring notion that supplants the facts of an individual life. Legacy is no longer concerned with "This is what I experienced" so much as "This is how I will be remembered," and that distinction is important—it's the difference between the actual person and the idea of the person.

In the case of Schultz, there's a potentially harmful stigma that may be attached to him because of Foxcatcher. (Schultz's beef is entirely with Miller and not with Tatum, whose performance he's continued to praise.) Sure, Schultz's name's out there again, but contrary to the cliche, there is such a thing as bad publicity. The troubled, underachieving, and self-destructive side of his character in the film can be potentially damaging to his future earnings as a public speaker and life coach. When Schultz detailed the differences between his life and the Foxcatcher's depiction of it, part of it seemed like clarification and part of it a CV.

With world leaders, the question of legacy is even greater, and Updegrove and Califano's stewardship of Johnson's legacy is to be expected. Califano's overreach attributing the Selma march to Johnson may be part of that narrative-making and myth-making nature of legacy, and it's something that stewards of a political figure do. People are more complicated than their legacies, obviously, and there are some quotations (albeit some of dubious attribution and) from Johnson that are tinged with the casual racism of his era. Johnson's a product of his time, and each era may have ceilings for progressive sentiments for segments of the population. If the enduring legacy for Johnson is The Great Society, the Johnson seen in Selma may cause audiences to question the president's commitment to his idea. The stewards want to make sure the man and the legacy are viewed as commensurate rather than separate.

For the filmmakers, notions of history and legacy are often secondary to concerns of narrative, and if there's one certainty, it's that lived-life generally doesn't have the arc of narrative-life.

Lived-lives are messy, lumpy, not-so-neat things, and to try to condense the events of a life down into a story that satisfies is difficult if not impossible. Even individual events in a life aren't so neatly compartmentalized to prove satisfying. There's a whole chain of cause and effect to consider, and complicated interactions, and seemingly insignificant moments that are charged with actual significance, and, of course, all the boring bits. The facts of lived-life become condensed, merged, filtered, omitted, and transformed when adapted to a retelling as part of this challenge of crafting narrative-life from lived-life. (The problem with most biopics is that they're usually just sketches or caricatures of their subject with gestures, some subtle and others overwrought, at an overarching story.)

In other words, like David Byrne sang: "Facts are simple and facts are straight / Facts are lazy and facts are late / Facts all come with points of view / Facts don't do what I want them to."

Filmmakers also have a certain distance from the events themselves and the historical players in the events, which leads to different takes on what unfolded. In Miller's case, he had access and cooperation from Schultz during the making of Foxcatcher, but since he wasn't a participant in the actual events, he comes at the material from a different point of view. For DuVernay and Selma, there's a generational distance to consider in her approach to the material, a component of race as well, and even a distance from one legacy (Johnson's) in order to focus on humanizing another legacy (King).

But in addition to facts and distance, there's also a question of individual concerns and point of view. Miller found certain aspects of Schultz's and du Pont's story interesting and chose to explore them in a way that appealed to his sensibilities, and DuVernay similarly found her own interests in the Selma march and tried to explore them. These unique concerns from Miller and DuVernay play roles in their depiction of actual people, actual events, and even the fictional elements that play with actual events. Creation and invention become necessary as part of making story-life. Even when the film is ostensibly about real life, it's at best an approximation, though hopefully the inventions are as carefully considered as the facts. (Inventions and omissions make their own difficulties in based-on-true-story stories. Take the Jimi Hendrix domestic abuse allegations in John Ridley's Jimi: All Is By My Side and the glossing over Alan Turing's persecution for being gay in Morten Tyldum's The Imitation Game.)

The ultimate difficulty of adapting real life to the screen is this parallax view of history. Different players in the actual events and different participants in the recreation and evaluation of these events will necessarily see something different or know something more or interpret a moment in a way someone else hasn't. It's the messy tangle when legacy narratives and historical narratives and the demands of narrative per se weave with the interests and obsessions of filmmakers.

The mess is unavoidable. But maybe it's also a necessary process, not just of filmmaking and adaptation but of how we revisit and reevaluate news and history. Consider Angelina Jolie's Unbroken, a biopic about Jack O'Connell, which was met with mixed reviews for being too neat and one note, perhaps too obsessed with the legacy rather than the actual man.

There's rarely a single definitive text about history, or a single narrative about what happened in an event. While potentially problematic, these films based on true stories can add an additional dimension to what's occurred, another shift in the angle of observation. The distance from an event allows for a potentially valuable perspective—not necessarily better or worse but just worthwhile.

Maybe the closest we can get is something true enough in general, even if moments in a film are disputed as acts of truthiness or outright fabrications. From there, we can then parse out the fictions and the intentions of the creators and consider how story-life and lived-life play into the overarching narrative of the film and the overarching scope of history.

It's a cop out of an answer, sure, but it's pretty honest.

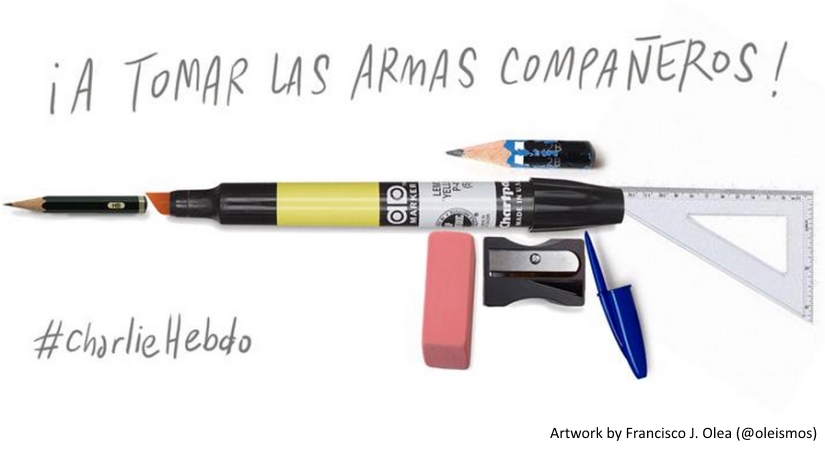

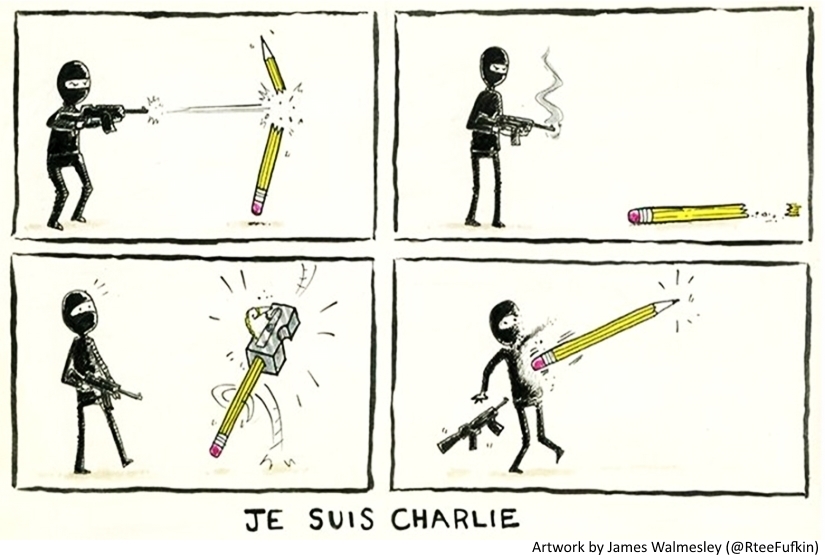

Nous Sommes Charlie Hebdo: Terrorism's Losing Battle Against Satire and Artistic Expression

Yesterday, France experienced its worst terrorist attack in more than five decades. At least two gunmen, brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi, entered the Paris headquarters of the weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo armed with assault rifles. The terrorists killed 12 people, including Charlie Hebdo editor and lead cartoonist Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier, several other members of the staff, and two police officers. As of this writing, both of the Kouachis remain at large, though a third suspect, Hamyd Mourad, reportedly turned himself in to French authorities last night.

The attack was prompted by Charlie Hebdo's anarchic satire—a particularly cheeky "nothing's sacred" approach the French call "gouaille"—which mocked the Prophet Muhammad as well as pretty much everyone else. Weeks after the September 11 attacks, the cover of Charlie Hebdo featured Osama bin Laden saying, "No hands," as in a kid on a bike shouting, "Look, Mom: No hands!" Another cover featured Pope Benedict XVI sneakily instructing a pedophile bishop to get into the movie business to keep safe just like Roman Polanski. This brand of satire led to a 2011 firebombing of the Charlie Hebdo offices. As Arthur Goldhammer wrote yesterday in Al Jazeera America, "The whole point of Charlie's satire was to be tasteless and obscene, to respect no proprieties, to make its point by being untameable and incorrigible and therefore unpublishable anywhere else."

Yet symbolically, Charlie Hebdo has come to mean more than what it was. In a sign of solidarity, many in mourning across the world have taken up the slogan "Je Suis Charlie" ("I am Charlie"; this article's headline "Nous Sommes Charlie" means "We Are Charlie"). Because of the audacity of the attack, the terrorists haven't destroyed Charlie Hebdo. Instead they have given a financially shaky magazine with a weekly circulation of 50,000 all the eyes of the world.

Fundamentalism and extremism of various stripes tends to involve a lack of self-awareness and a lack of self-reflection, though mostly fundamentalists and extremists lack a sense of humor. Anyone who takes themselves or their ideology so seriously that they resort to murder or threat of violence after feeling offended is, frankly, an asshole.

I'm not saying that I'm an arbiter of what people should or should not be offended by—your right to be offended is wholly your own—but what I am saying is that there are better and more constructive ways to express your feelings than harming others or threatening to harm others, and if you harm others or threaten to harm others simply because you are offended, you are an asshole. This goes for the people who carried out these attacks, the hackers at Guardians of Peace trying to stop the release of The Interview, the belligerent Gamer Gaters who put commentators and developers in their crosshairs, the person or people who bombed the NAACP office in Colorado Springs, the man who murdered Theo van Gogh, and so on. It takes a special kind of ignorance and cowardice to justify one's violent intentions using religion, country, or some other ideology.

The Charlie Hebdo gunmen reportedly screamed that Muhammad had been avenged after their act of murder, as if Muhammad had nothing better to do than read a French weekly magazine.

Assholes.

What these attacks and threats of violence ultimately do is set back the ideology that carried them out by creating a solid opposition against said ideology. It's the sociopolitical version the Streisand effect, in an odd way. In rallies throughout Europe and in posts online, there are "Je Suis Charlie" signs and #charliehebdo. If Charlie Hebdo was mostly known in France before the attack, it is now an international symbol.

Jon Stewart opened last night's The Daily Show expressing his condolences for the staff of Charlie Hebdo. "I know very few people go into comedy as an act of courage, mainly because it shouldn't have to be that," Stewart said. "It shouldn't be an act of courage, it should be taken as established law. But those guys at Hebdo had it and they were killed for their cartoons." (On The Daily Show's website, "Je Suis Charlie.") The Onion also had a finely neutered and somber take on the tragedy with the headline "It Sadly Unclear Whether This Article Will Put Lives At Risk." It's worth reading in full. Hell, Louis CK even wore a makeshift Charlie Hebdo t-shirt when he performed at Madison Square Garden last night.

The chant at protests in which an especially horrific action has occurred is "The whole world is watching." For a while, out of anger and out of sadness, the whole world is Charlie. George Packer in The New Yorker yesterday concluded his piece with line "We must all try to be Charlie, not just today but every day."

To harm an artist is to fight a hydra.

[iframe id="http://media.mtvnservices.com/embed/mgid:arc:video:thedailyshow.com:09f585e8-8f8f-4727-81d1-0eb972cc325d" align="center" autoplay="no" maxwidth="825"]

Of course, one of the major fears is that the Charlie Hebdo shooting will foment an already ugly right-wing anti-Islamic sentiment that's been building throughout Europe. The terrorists have not just set back their own cause, but they have made things worse for Muslims who are far from radical and simply want to live normal, peaceful lives. On American TV, Bill Maher didn't help matters. Maher claimed on Jimmy Kimmel Live that hundreds of millions of Muslims supported an attack like the one on Charlie Hebdo.

While Maher's "hundreds of millions" claim is probably way off—it's supremely facile to assume the actions of a handful of people speak for hundreds of millions of people—there's at least some precedent behind the claim. Salman Rushdie made a particularly bold statement yesterday in condemnation of the Charlie Hebdo shooting, and he knows firsthand about the horrors of religious extremism. In 1989, the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Rushdie for writing The Satanic Verses. This led to threats of violence against Rushdie, the murder of the novel's Japanese translator, and assassination attempts against other individuals around the world associated with the release or translation of the book.

Rushdie's statement regarding Charlie Hebdo reads as follows:

Religion, a medieval form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. This religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today. I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity. ‘Respect for religion’ has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.

Some of the best responses to the murder of Charb and his fellow cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo have come from artists around the world. Time, The Daily Beast, Reuters, Comics Alliance, and numerous other outlets have run galleries of art in tribute to those who died. Though many are touching, most have a kind of anarchic revenge about them, with an emphasis on art as way of overcoming ideological repression. James Walmesley tweeted one of my favorite cartoons about Charlie Hebdo, and Francisco J. Olea tweeted out his call to arms to the artists of all nations. In the face of this act of terrorist negation, here is an overwhelming counterattack of creativity. Don't expect it to end.

Charb and his fellow writers and cartoonists have become heroes. Numerous new outlets have cited a 2012 interview with Charb at Le Monde with a line that speaks to the courage of a good satirist: "I am not afraid of retaliation. I have no kids, no wife, no car, no mortgage. It surely is a bit dramatic, but I'd rather die on my feet than live on my knees."

As for Charlie Hebdo, the next issue will come out on Wednesday with 1 million copies in print. Further, Charlie Hebdo will continue to be published. Patrick Pelloux, a contributor to the magazine, said in an interview with iTele, "Charlie Hebdo will continue because [the terrorists] haven't won. [The victims] didn't die for nothing. There is no hatred to have against Muslims and everyone, each one of us, in front his home, every day must keep the values of the French Republic alive."

Take that, assholes.

These large outpourings of compassion and creativity remind me of George Saunders' Manifesto: A Press Release from People Reluctant To Kill for an Abstraction (PRKA), a short satirical (though ultimately sincere) essay I read whenever the world seems senseless and humanity doomed. It's a fictional press release from an organization comprised of regular people trying to live without harming others and who want to find some modicum of joy and dignity in an existence that seems hellbent against such simple things.

Saunders' piece closes with these words:

To those who would oppose us, I would simply say: We are many. We are worldwide. We, in fact, outnumber you. Though you are louder, though you create a momentary ripple on the water of life, we will endure, and prevail.

Join us.

Resistance is futile.

The flesh may be vulnerable, but people united not quite so, and the pen is mightier still.

The Uncanceled Interview: Obama Weighs In, Sony Backtracks, and Everything Gets Even Weirder

What a difference a few days make.

On December 17th, Sony canceled the Christmas release of The Interview, fearing further damage and information leaks from hackers. At that time, Sony implied that they had no plans to release the film at all, including on DVD, Blu-ray, or VOD. Even symbolic screenings of Team America: World Police were canceled by Paramount out of fear of retaliation by hackers.

Numerous commentators weighed in about Sony's decision, suggesting cowardice was the reason that they bowed to the demands of the hackers reportedly linked to North Korea. The hackers made an additional request that Sony erase all traces of The Interview's existence, which includes the official website, all online videos, and preventing the leak of pirated copies online.

President Obama weighed in on the matter during a year-end press conference on December 19th, saying he felt that Sony had made a mistake in canceling The Interview's release. "We cannot have a society in which some dictator some place can start imposing censorship here in the United States," Obama said. "Because if someone is able to intimidate folks out of releasing a satirical movie, imagine what they start doing when they see a documentary they don't like, or news reports don't like. Or even worse, imagine if producers and distributors and others start engaging in self-censorship because they don't want to offend the sensibilities of somebody whose sensibilities probably need to be offended."

And then, after some waffling and dithering, Sony decided to uncancel The Interview, releasing it in select theaters as well as various online platforms.

The Interview played on just 331 screens across the United States. Two other high-profile Christmas new releases, Into the Woods and Unbroken, played on 2,440 and 3,131 screens, respectively; the critically acclaimed Selma opened on just 19 select screens. According to Box Office Mojo, The Interview made $2.8 million in theaters during the long weekend.

The Interview fared much better online. Deadline reported that The Interview made $15 million through online rentals and sales. Sony estimated that there were 2 million rentals or purchases made through YouTube, Google Play, Xbox Live, and the website SeeTheInterview.com. Of course, The Interview was also illegally downloaded 750,000 times on Christmas Day alone. One assumes the number of legal and illegal watches online have to be about the same by now.

While reviews of the film continue to be mixed—the symbolic 10/10 user rating on IMDB just a week and a half ago has since dipped down to 7.7/10 following the film's release—the impact of this cultural moment is still so strangely resonant. There was no 9/11-style violence in any of the 331 theaters that screened the film, unless singing Lee Greenwood's "Proud to Be an American" is considered an act of terrorism. And while the money made so far doesn't cover half of the film's budget, there is a potential for further day-and-date digital releases of certain films in the future. Maybe those films can get some free publicity from North Korea.

While the North Korean government still denies involvement with the Sony hack, they are extremely upset with the film's release. (Earlier in the year, they declared The Interview an act of terrorism and and act of war, after all.) There have recently been country-wide internet outages, which North Korea blames on the United States, and they may not be wrong since Obama suggested there'd be some form of measured response to the hacking. On December 27th, North Korea's National Defense Commission issued a statement calling President Obama "the chief culprit" behind the The Interview's eventual release. The statement continued with the following not-so-veiled racist remark: "Obama always goes reckless in words and deeds like a monkey in a tropical forest."

In an odd example of the Streisand effect in full effect, however, the North Korean government's months of outrage over The Interview has made its own oppressed citizens hungry for the film. Screen Rant ran a piece stating that North Koreans are currently paying as much as $50 on the DVD black market for pirated copies of The Interview. For perspective, most pirated DVDs in North Korea run about 50 cents. Foreign media has increasingly become problematic for the North Korean regime, as films and television shows from abroad are showing its citizens greater prosperity and different ways to live (i.e., not abject poverty in a totalitarian dictatorship).

But maybe the most fascinating part of this post-release phase of The Interview are the doubts about the official story of the Sony hack. Whether these suspicions are warranted or a kind of foil-hat-trutherism, a number of internet security experts feel that North Korea might not have been responsible for the hack. Even before The Interview was canceled, I recall seeing a security expert on the news suggest that an angry Sony employee was the more likely culprit. A long-term inside job makes sense simply given the amount of information released and the nature of the hack. Much of the focus from those who doubt the FBI's story is now on someone identified as "Lena," who worked for Sony in Los Angeles for 10 years and is associated with the Guardians of Peace.

Everything continues to become curioser, and all because of a dick-joke movie. Again, the real-world happenings around The Interview prove to be far more fascinating than the events depicted in The Interview. I can't wait for the documentary.