[Review] Terminator: Genisys

Terminator: Genisys didn't have the easiest start in life, having been revealed in a series of cast photos for Entertainment Now so ridiculously posed and doctored that they looked more like a deliberate parody of overwrought movie marketing than serious promotional material. The first trailer, seen below, didn't inspire much greater enthusiasm, relying heavily on callbacks to James Cameron's original movie and trying to sell a decidely girlish-looking Emilia Clarke as the hard-ass Sarah Connor. That's without even mentioning the name, its spelling as ridiculous and '90s inane now as it was when first revealed.

Everything leading up to the movie seemed to hint at a storm brewing on the horizon, a disaster lingering in the near future whose inevitability grew ever more unstoppable as the time drew nearer. I don't know whether it's therefore a relief to report that Genisys appears to have changed its fate for the better when all it means is, much like the Sisyphean battles Sarah Connor seems unable to extricate herself from fighting, the apocalypse may have been averted, but that doesn't mean what's left in its place is an especially good time.

[youtube id="62E4FJTwSuc"]

Terminator: Genisys

Director: Alan Taylor

Rating: PG-13

Release Date: July 1st, 2015

James Cameron's name has been plastered all over the movie's recent advertising and one can only assume he looked at two possible futures - one where Genisys is a success and he presumably gets to wallow in an avalanche of royalties, and another where Genisys is the box-office bomb it's looking to be and suddenly he's got to put on hold that order for another deep sea submersible - and decided he liked the first one just a little more. Why else he would willingly attach his name, even peripherally, to a movie so profoundly mediocre rather defies comprehension - although let's not forget that he also spoke favourably of Terminator 3: Rise Of The Machines around the time of its release as well.

Genisys, on balance, is better than the third and fourth movie in this series increasingly desperate for any sense of creative direction, though that's not saying much. Rise Of The Machines was a tamer, lamer rehash of T2 with a surfeit of insufferably camp humour, while the most memorable thing about McG's Terminator Salvation was Christian Bale's on-set meltdown at the lighting crew. To its credit, Genisys tries something new, messing with the series chronology to perform a semi-reboot in the style of J.J. Abrams' 2009 Star Trek. Sarah Connor has now been raised since childhood by Schwarzenegger's T-800, Judgment Day has been pushed back to coincide with the release of a global operating system called (you guessed it) Genisys, and someone or something seems to be producing surgery on the timelines they are hopping between.

The novelty value of the movie screwing with its own history keeps it afloat for longer than it deserves. While the plot, again, amounts to nothing more than Sarah and her cohorts having to stop Skynet before a literal countdown reaches zero, there are some interesting if largely unexplored ideas introduced as a result of all the temporal upheaval, with a couple of the character relationships sent in potentially interesting new directions. One of the movie's major twists was revealed in the second trailer and is at the epicentre for much of this, but in the off-chance you haven't been spoilt already, I won't do so here. Though these elements don't add a great deal to Genisys itself, but at least lay the groundwork for better movies in the future. That's hardly a great magnitude of praise, especially with Marvel having long since worn out the welcome of movies-which-are-actually-adverts-for-later-movies, but is perhaps the most interesting thing about an action blockbuster which otherwise seems content to plod through the formulaic motions.

Though hardly the disaster many would understandably have been expecting, Genisys makes a series of lousy choices which holds it back from leaving any sort of positive impression. Most damagingly, both Emilia Clarke and Jai Courtney are severely miscast. While Clarke simply cannot pull off the warrior woman act convincingly despite her best efforts - the recoil of the Desert Eagle she fires in her big introduction would realistically tear her hand off at the dainty wrist - Courtney gives a non-performance as Kyle Reese that is among the flattest I can ever recall seeing. Reese is a man who has lived his entire life being hunted in an apocalyptic wasteland before time travelling back to the past and discovering history is changing around him, yet the only emotion he even comes close to expressing is mild disinterest. Yes, the script is weak, but the character has enough context and precedence that even a mediocre actor could dig up a slither of the pain and sadness and fear that Michael Biehn originated in the role. Courtney is a black hole at the movie's heart, leeching away interest with every second of his extensive screentime. At least Sam Worthington and the Hemsworths, his predecessors as pre-fab Australian hunks, had the self-respect to stick with inert blandness.

On the plus side, Schwarzenegger seems to have rediscovered the fun in his signature role, despite being lumbered once again with a tedious line in character-breaking campy humour. The difference between his performance in Genisys, when even his deliberately mechanical line recitals have some gusto behind them, and his bored meandering through Rise Of The Machines could not be more apparent, even if it ultimately amounts to little more than small inflections and gestures. An engaged Arnie is a fun Arnie and while he can't fully compensate for Courtney's dead-eyed charisma vampiricism, he at least provides some successfully nostalgic pleasures amid the otherwise mixed bag of series callbacks. Among these, the weightless CGI sinks any pleasure that might have been had from the appearance of a 'young' T-800 Arnie (itself a repeat of a trick pulled in Salvation) and generally undermines the major action scenes with a visibly jarring disregard for even the most basic laws of physical motion and mass.

Considering the value that the Terminator series places on the importance of humanity's survival in face of mechanised extinction, most of the present day world in which Genisys takes place seems to have been rendered by computer. Cameron's movies were rough, dirty epics that were as scary as they were cool and as brashly emotional as they were exciting. Genisys hints at interesting plot convolutions but doesn't get around to showing them, while its inert casting kills any humanity in the central relationship and hollow CGI creates action sequences that are easy to sit through but impossible to engage with. There's some pleasure to be had in a Schwarzenegger back on form, the refrains of that iconic theme, or JK Simmons almost making a character out of a cardboard cut-out, even if he really should have been playing Dr. Silberman, if only to keep series tradition alive. Every ambition the movie has was already achieved to greater effect in the underrated TV series, The Sarah Connor Chronicles, while the rest seems trapped between rehashing the pleasures of the past and promising better things in the future, all while delivering little in the here and now.

RIP Patrick Macnee, Star of The Avengers TV Show & Role Model For Boys Everywhere

Patrick Macnee, best known for starring as John Steed in the '60s British television phenomenon, The Avengers, died of natural causes yesterday, aged 93, at his home in California.

Some of you may have read the article I posted last month about the impact The Avengers had in pioneering powerful female characters on television. For those who still remember the show, often the first thing that comes to mind is Diana Rigg's Emma Peel, the show's karate-chopping, catsuited co-lead between 1965-1967 who became an immediate fashion and feminist icon of her time. While the show's array of brilliant and beautiful female characters may live most vividly in the popular memory for their impact on culture and beyond, it was Macnee's John Steed who was its constant anchor, lasting its entire run from 1961-1969 before returning for two more years between 1976-1977 with the New Avengers revival.

My article focused on the show's positive impact for women, but it should never been forgotten how important Macnee's role as Steed was in providing a role model for young boys to look up as well. On the surface, Steed is often interpreted as representing the good in old-fashioned values where his female partners represented modernity and youth. While that is all true, it overlooks what a nuanced, progressive character Steed actually was. He embodied all the wonderful aspects of the traditional English gentleman, always gracious in manner, quick of wit and exquisite - barring a few questionable casual shirts in the Tara King era - of dress, showing how a masculine role model could evolve to work alongside women as equals.

He was cheeky and flirtatious, instantly loveable thanks to Macnee's avuncular charm, but never patronising or domineering. He respected his female partners as effortlessly as they respected him. Just as Honor Blackman's Cathy Gale, Diana Rigg's Emma Peel, Linda Thorson's Tara King and Joanna Lumley's Purdey gave women figures to strive towards, so too was Patrick Macnee's Steed an exemplar for all good men to aspire to. Diana Rigg, in particular, has credited Macnee for his support during a difficult time towards the end of her tenure on the show when she discovered that, despite being the star, she was being paid less than the cameraman.

Looking back at Macnee's unconventional childhood, one can perhaps find the roots of the positive values he brought to the show and his character. Like Steed, Macnee had something of the eccentric aristocrat about him from birth, with his mother Dorothea, socialite niece of the 13th Earl of Huntington, going into labour at a party and rumoured to have given birth to him in a carriage halfway down Bayswater Road. His parents divorced when his mother came out as a lesbian, and it was she and her partner Evelyn who raised the young Patrick and paid for his education at Summerfields, where he became acting acquaintances with Christopher Lee, and then Eton. His father was no less eccentric, a racehorse trainer nicknamed 'Shrimp' for his lack of height, who was sent home from India in disgrace after urinating from a balcony onto the Raj and his officials at a race meeting. It was his fondness for fine clothes that inspired the same quality in Steed. Patrick inherited his parents' knack for challenging social mores and was expelled from Eton for selling pornography and bookmaking for his fellow students. In other words, the friend we all wish we'd had.

After serving in the Motor Torpedo Boats during the Second World War, saved from D-Day thanks to a bout of bronchitis, he began his screen acting career in Powell and Pressberger's 1943 classic, The Life And Death Of Colonel Blimp. After seeking new opportunities in North America, he returned to England in 1960 and was cast in his defining role as Steed a year later. The part dominated the rest of his career, though he also made high-profile film appearances in This Is Spinal Tap and A View To A Kill (joining Blackman, Rigg and Lumley as Avengers alumni going on to star in Bond movies), along with television guest spots in Columbo and The Love Boat among others. He also popped up in the video for Oasis' seminal '90s Britpop hit, Don't Look Back In Anger.

It will nevertheless be as Steed that Macnee will undoubtedly be most fondly remembered by his many fans. As sad as it is to discover his passing, I am proud to have had him as a personal hero growing up, the inspiration for many ridiculous memories of putting on a bowler hat and grabbing an umbrella before running outside to recreate and invent various episodes of The Avengers in the garden. The tributes pouring in show such memories are shared just as fondly among many others across the world. Patrick Macnee, you always kept your bowler on in times of stress, you conquered every diabolical mastermind who crossed your path, and looked more worldly and debonair in a suit than any man has before or since. You were and are my hero, the original Avenger, and my bowler will forever be doffed to your memory.

R.I.P. Patrick Macnee, 1922-2015.

[Review] The Face Of An Angel

British director Michael Winterbottom may be many things, but consistent isn't one of them. Despite his prolific output, it's impossible to know which version of the director will show up: the dry, subtly effective helmer of The Trip miniseries; the bold revisionist who adapted Tess Of The D'Urbervilles in India for Trishna; the composed, naturalist eye behind Everyday; or, less encouragingly, the indulgent provocateur of 9 Songs and tonal blunderbuss who wasted a fine cast in The Look Of Love.

Unfortunately, the Winterbottom helming The Face Of The Angel is the same man behind the insufferable 9 Songs. Any veneer of artistic boldness is wiped away by insufferable indulgence, demonstrating little genuine purpose beyond attracting attention through provocation and needless visual gimmickry and turning a potentially fascinating real-life murder investigation into an excuse for narcissistic self-meditation. The movie may be dedicated to the memory of Meredith Kercher, but the only person its director seems genuinely interested in exploring is himself.

[youtube id="ag_I15RBl-0"]

The Face Of An Angel

Director: Michael Winterbottom

Rating: R

Release Date: June 19, 2015

The story is ostensibly a fictionalised examination of the Meredith Kercher murder through the eyes of an English film director as he slowly loses his mind while seeking inspiration for the most appropriate way of telling the story. The most oft-repeated theme is whether it is better for art to depict the literal truth or offer a fictionalised perspective through which truth can be interpreted, examined and perhaps eventually, clarified. The story does not attempt to untangle the Kercher case so much as look into the way it was reported and what it says about both those doing the reporting and those they were reporting to. Thomas, the director played by Goodbye Lenin's Daniel Brühl, is coming off the back of a flop and needs a hit to revitalise his career. A murder committed in the picturesque Tuscan city of Siena by an American student and her Italian boyfriend offers compelling material for his financiers, but he struggles to find an original take on a case around which most people seem to have already formed a version of the truth in their heads.

Turning a real-life murder into the story of a director's creative crisis feels a little tasteless, but such issues could be easily overlooked had the movie any original insights into the situation and what it says about the social circumstances in which it played out. The media's determination to spin their own versions of what happened is a potentially fertile source of inspiration, yet Winterbottom offers the idea little more than lip service. Supporting characters parrot on about the dividing line between truth and fiction, yet Thomas' mental state is the real centre of attention. That one character even comments on this, suggesting the story shouldn't be turned into that of a middle-aged director losing his way, highlights rather than mitigates that indulgence through commentary. Thomas isn't even interesting enough to hold attention. His meandering through the streets of Siena, pontificating about parallels between the case and the Inferno section of Dante's Divine Comedy (much to the bemusement of his backers), all the while hallucinating and doing copious quantities of drugs, is neither as deep or original as Winterbottom seems to think it is. There is none of the self-loathing or subversive humour which anchored Charlie Kaufman's Adaptation, the 2002 film to which Face Of An Angel owes a clear debt.

The cast is solid enough, though supporting characters struggle for definition in the wake of Winterbottom's focus on Thomas, whom even the usually dependable Daniel Brühl cannot salvage into anything other than a tiresome mope. Kate Beckinsale's Simone exists solely within the context of her relationship to him, while Genevieve Gaunt's Amanda Knox analogue, Jessica Fuller, is never explored beyond other characters telling us what a media-savvy star she is supposed to be. The Kercher figure, Elizabeth Pryce (Sai Bennett), is an afterthought at best. Surprisingly, the one who emerges from the film with far and away the most credit is first-timer Cara Delevingne, who takes a nothing role as a twenty-something art student, Melanie, and infuses it with a liveliness and warmth all her own. There's a valid argument that she is simply playing herself, but she manages to pack considerably more into her limited character than more experienced actors like Brühl and Beckinsale. The movie becomes more interesting and likeable every time she pops up, with none of it down to the staid writing and directing.

Outside Delevingne's inspired casting, Winterbottom struggles to find any sort of spark to bring the movie to life. He dallies with themes he has tackled more successfully in movies past, but just as Thomas finds himself wandering aimlessly through Siena's dark and foreboding streets, so too does Winterbottom repeatedly head down thematic and narrative blind alleys. The incessant meet-and-greets which take up so much of the movie's running time feel like filler while the director tries to make up his mind which undercooked gimmick to deploy next, whether demonic hallucinations or thriller-ish hints at the secret motivations of a morbidly philosophical local, all reliant on a blunt musical score to overemphasize moments of intended impact. However questionable the taste of tackling a murder case still fresh in the memory, the story is one so interwoven with juicy strands of social and cultural commentary that it's remarkable how little ends up being said. Entire movies could be built around the Kercher case's sexual dynamics, the media's depiction of women, or holistic connections to youthful hedonism in the modern age, yet the most interesting take Winterbottom can come up with is perfunctory, winking self-flagellation for his own lack of inspiration.

[Review] Inside Out

Inside Out is another movie this summer to be breaking box-office records, having achieved the biggest ever opening weekend for an original movie despite coming second to the behemoth that is Jurassic World. Considering Hollywood's laser-focus on sequels and franchises, that's something to be celebrated. That it's a return to original material for Pixar, whose phenomenal run of form has taken something of a dip in recent years with the likes of Cars 2 and Monsters University (some would include 2013's Brave, though I enjoyed that one), will also be welcomed by fans.

My personal affection for the studio varies, having found several of their movies to be outstanding (Ratatouille, Up, Toy Story 3, The Incredibles), others (both sets of Cars and Monsters movies) no better than the much-maligned output of animation rival Dreamworks, and in one case, borderline cynical (Wall-E) in its advertising to a young audience. Given the rave reviews Inside Out has been receiving, I was looking forward to rediscovering a re-energised Pixar at the top of its game. Unfortunately, Inside Out continues the recent trend of the studio struggling to find new things to say.

[youtube id="seMwpP0yeu4"]

Inside Out

Director: Pete Docter

Rating: PG

Release Date: June 19, 2015

The movie is a metaphorical journey through the emotional turmoil of Riley, a young girl on the verge of adolescence who moves away with her parents from a comfortable life in Minnesota to the uncertainty and challenges of a new start in San Francisco, where her father has taken a non-specified job. The emotions in Riley's head are anthropomorphised in the form of Joy (voiced by an ebullient Amy Poehler), Sadness, Disgust, Fear and Anger. It's an interesting enough idea, but one very much of a kind with Pixar's affinity for characters existing outside the perception of the human world and their commonly explored themes of growing up and moving on after difficult periods in life.

The problems begin at the very start - and no, I'm not talking about the animated short, Lava, which precedes the movie, although it too is disappointingly corny despite an appealingly oddball premise - with Joy opening the movie with a prolonged, exposition-heavy monologue explaining how memories work, the difference between standard memories and core memories, how they're organised, the role played by the five emotions in doing so... it's lumbering and overcomplicated, and possibly unnecessary. The visuals (of Riley being born, experiencing her first two emotions) tell an effective enough little story that the fundamental ideas are seeded without the need for oppressive wordiness. Considering the studio's history with exquisitely crafted silent storytelling, it's an uncharacteristic failing.

Unfortunately, it's one which Inside Out repeats over and over again, introducing a never-ending stream of concepts to be explained in-depth despite rarely being any more useful than one in a long line of contrived obstacles between getting the lost Joy and Sadness back to Riley's emotional headquarters (solid pun), all while overcomplicating and straining the credibility of her extensive inner world. It's a strange case of the broad strokes of that world feeling oversimplified and discordant, while the minutiae is overexplained to the point of clogging up the narrative engine. Among Riley's many internal mechanisms are long term memories stored in mazes, personality traits represented as islands, a production studio for dreams, a train of thought carrying interchangeable facts and opinions (zing) between various locations, a spatially-distorted area for abstract thought... there's an internal logic of sorts piecing it together, but it feels too scattershot and segmented to work in the moment, hence the endless explanations. It's not the richness of the ideas that's the problem, but the movie's inability to visualise or clarify them succinctly.

With so much exposition to get through, character development also draws short shrift. It doesn't initially matter that Riley is something of an everygirl, lacking strong identifying characteristics beyond an affinity for hockey, but until the very end of the movie, Joy is unchangingly defined by her eponymous emotional imperative, while Sadness' purpose is merely put in a slightly different and somewhat self-evident context. The remaining three emotions, left governing Riley's mental state in the interim, barely register despite solid voicework from the cast. The events of Riley's outer existence may be of decidedly secondary importance to what is motivating them, but enough time is spent in the human world that the copy + paste nature of her generic life becomes more and more of a drag as things progress in the entirely predictable direction.

The movie pulls together at the end, finding a slightly more poignant theme in its final moments than the 'sadness is important too!' idea which dominates 90% of proceedings and treated as if some grand revelation, despite being covered in greater depth in an episode of South Park a while back, not to mention Doctor Who. Amy Poehler's charming voicework is invaluable in pulling the movie through a middle section which has no particular relevance to the thematic outcome of the climax, and a small number of memorable jokes (particularly one about an earworm-y gum jingle) distract from the stark absence of laughs elsewhere. Phyllis Smith also does terrific things with Sadness, a very difficult character, making an engaging double act between her unwavering pessimism and Joy's absolute optimism.

Ultimately, even the movie's biggest strengths feel like they're retreading ground that Pixar has already extensively covered. A character, not featured in any advertising and therefore not to be spoiled here, turns up with the sole purpose of meeting a sad end, and it's hard to believe anyone who hasn't seen a movie before won't immediately see his fate coming or the contrived machinations required to get him there. The movie's two funniest jokes come during the end-credits, one involving cats and the other dogs, recalling director Pete Docter's vastly superior previous effort for the studio, Up!, whose structure and themes Inside Out attempts to replicate but with much of the grace and silliness (an inconsequential but amusing trip through abstract thought comes closest) lost in translation. There are some interesting moves in play, most notably the absence of any sort of villain, but for the reams of exposition which turn so much of the central narrative into a slog, the movie fails to give those details any meaningful substance in Riley's emotional development, while her human existence feels rote at best. Mixed feelings for all of us, then.

[Review] Burying The Ex

Joe Dante is one of those directors you wish would get more work. At a time when any semblance of identity or creativity in blockbuster filmmaking is being increasingly calculated, focus-tested and formula-driven out of existence, Dante at his best brings a spirit of gleeful, unpredictable anarchism, a joy at throwing away the rulebook that is both very much his own and the product of his mentorship at the hands of the great B-movie maestro, Roger Corman.

Burying The Ex sounds like ideal Dante material, concerning a young horror buff, Max, struggling in his relationship with a controlling girlfriend, Evelyn, only for her to be hit by a bus on the day he finally decides to break up with her, then come back from the dead in zombified form just as he moves on and meets a kindred spirit from a nearby ice cream parlour. Unfortunately, despite all the premise's potential for Dante's brand of gunk-splattered cartoon chaos, he struggles to bring any life to an uninspired, pedestrian script that feels more like the extended pilot for a middling network sitcom called So I Dated A Zombie than a comeback cinematic outing for a great genre director.

[youtube id="MYlDjF8-sb4"]

Burying The Ex

Directors: Joe Dante

Rating: R

Release Date: June 19th, 2015

The movie is rated R, specifically for sexual content, partial nudity, some horror violence, and language. All of that may be technically true - the 'nudity' is especially partial - but far from any degree that one might expect to trouble the censors were this a higher budget release, backed by a more influential major studio. There's plenty of blood, but mostly used to cover faces rather than douse the walls, while a brain-eating scene is edited in such a way that any real semblance of gore is restricted to quick flashes. Dante's affection for discharging large quantities of boldly coloured gloop is satisfied by the zombified Evelyn projectile-puking embalming fluid all over the terrified Max, but played strictly for laughs - none too effectively, it should be said, making a jarring tonal shift amid one of many lackadaisical, drawn out dialogue scenes that should be more fun and energetic considering the material being covered - and hardly the sort of thing to turn away from. It's one of the tamest R-rated movies for a long time and the feeling pervades that the rating gives the movie's horror bona fides more credibility than they deserve.

Part of that is surely a result of the low budget, which leads to a significant number of scenes taking place in Max's front room. Dante had great fun contrasting the safety of suburban decorum with the ravages of the supernatural in Gremlins, but Alan Trezza's script denies him the chance to really dig into what zombified havoc Evelyn is capable of unleashing on Max's slow-paced hipster existence beyond one bout of vomiting and a handful of demonstrations of super-strength. In fact, there's a real argument that she does more damage in redecorating his front room prior to her (first) demise than she ever does following her resurrection. What's left is a series of quickly wearisome back-and-forths in which Evelyn re-asserts her desire to covert Max to the undead so they can be together forever, followed by his expressions of disgust at that desire and her steadily decaying flesh.

The unadventurous script limits the strong cast, of which Anton Yelchin, playing the put-upon Max, feels most subdued. Yelchin is a charismatic actor who has made a good impression in minor roles in not-so-good movies, but he plays Max so sleepily and lacking any response beyond mild surprise and concern at what should be a terrifying situation that he's hard to have sympathy for when he himself barely seems concerned by what's happening. True, he's not supposed to be a character of any great assertiveness or courage, but Yelchin tips the balance too far until it drops into virtual indifference. His half-brother, Travis, is supposed to be the more ribald and confident of the two, but is such a tedious slobby womaniser stereotype that, rather than being an invigorating presence who pushes Max to stand up for himself, it's a relief whenever he exits a scene. It also speaks to the movie's disappointing safeness that he boasts of sleeping around not with centrefold models from Playboy, but FHM, a magazine, like the character, stuck in eye-rolling late-90s ideas of laddish masculinity.

Ashley Greene fares better as Evelyn, pushing back against the tame material to unearth a little of the sadness behind her character's anger and control-freakery. The obsessive, domineering ex-girlfriend is another tired cliché, but Greene's history with the Twilight franchise makes for savvy casting as she finds small traces of humanity in her zombified form. Perhaps one of the movie's most debilitating flaws is that it in fact makes the living Evelyn too likeable and sympathetic, justifying her controlling nature with a sad backstory and a genuine, if overbearing, desire to love and be loved. Her eco-conscious do-goodery (working for a firm called 'Live Green Or Blog Hard', one of a number of not-quite-funny-enough Simpsons-esque workplace names) may be pushy and annoying, but it's hard to deny she has a point when calling out Max for not showing any motivation to improve his lot despite constant complaining. She's the most fully rounded character in the movie, far moreso than Alexandra Daddario's dreamgirl sweet Olivia, entirely defined by liking all the same stuff as Max, a dating site approach to a romantic lead where compatibility is calculated exclusively by the number of shared interests.

What is the real stake through Burying The Dead's heart is that Shaun Of The Dead, an even more low-budget zom-com, did everything Dante's movie tries to do to much greater effect eleven years earlier. The movie skirts around the idea of relationship angst among geeky mid-twentysomethings, but Shaun committed more fully to the idea of the difficulty of youngish men finding a direction in life outside their nerdy and nostalgic preoccupations, all the while being significantly scarier, gorier, sweeter and funnier. Nick Frost's Ed, in particular, is a much more sharply observed depiction of what Travis should have been.

There are glimpses of the picture Dante might have made had his budget been bigger, the writing been sharper, and had he himself maybe been twenty years younger, but they are few and far between, in the end only growing the disappointment that what ended up on the screen is so consistently stuck in second gear and tepid in its execution of already underwhelming ideas. Ashley Greene in particular deserves better, while Alexandra Daddario continues her wait for a movie role which puts her natural affability to more lively use than the girlfriend role. A Dick Miller cameo and a handful of amusing sight gags provide the slim pickings for Dante's fans, but as welcome as it is to see him back in any sort of cinematic work, it's a shame the result shows few real signs of life.

[Review] Jurassic World

Many people expected Jurassic World to be a hit, though few would have predicted quite how big a hit it would turn out to be. In retrospect, it's easy to appreciate how complete the movie's formula actually is: dinosaurs will always be a major draw for children, especially when fighting other dinosaurs, while older viewers have the strong nostalgia factor of Steven Spielberg's 1993 adaptation of Michael Crichton's novel, Jurassic Park, to lure them in. Throw in one of Hollywood's fastest rising stars in the shape of Chris Pratt, and suddenly that record-breaking take doesn't seem quite so surprising.

Despite its big reputation, the original Jurassic Park never won me over as completely as those whose nostalgia is among the many reasons World is on its way to global domination. There's no question that Park was an extraordinary cinematic event, one of the few movies of the past thirty years to inspire a genuine sense of awe in its viewers, but whether it coheres as a great film in its entirety, rather than a handful of magnificent scenes and a cast which happened to be a perfect fit for the material and each other, is up for debate. Regardless, the moments when it really delivered are rightly celebrated among the finest moments of Spielberg's glittering career and few can deny its importance as a cultural phenomenon of its time. For all its astounding financial success, Jurassic World seems unlikely to be held in such high regard in twenty years' time.

[youtube id="RFinNxS5KN4"]

Jurassic World

Director: Colin Trevorrow

Rating: PG-13

Release Date: June 12th, 2015

That's not to suggest Jurassic World is a bad movie per se, but one which is best taken with strongly tempered expectations. It delivers all the dinosaur-on-dinosaur action that viewers will be expecting and is certainly the best of the three Jurassic Park sequels, though that's faint praise if ever there were such a thing. It's a movie which feels acutely aware of the likelihood that a strong percentage of its audience will be children and subsequently inhabits that PG-13 middle ground where no matter how great the carnage depicted on-screen, everything remains strangely and distractingly bloodless.

One of the most uncomfortable examples of this is a prolonged, grossly misjudged death of one of the supporting characters, who for a good thirty seconds is thrown through a procession of increasingly nasty torments before finally being put out of their misery, all without a single drop of blood being spilt. There are many reasons to object to this scene in particular, not least its discomforting delight at inflicting extended cruelty on a character who seems to be being punished for nothing more than absent-mindedness, but the movie's refusal to show the consequences of its depicted actions even while pushing so far into unpleasantness makes for an uncomfortable disconnect from reality and a sense of weightlessness which permates the rest of the movie.

Taken strictly on the level of spectacle, the movie hits its marks comfortably. Director Colin Trevorrow emphasizes the wonder and scale of the park, which has been rebuilt and reopened on the same island as the original in one of countless nods. The iconic John Williams score - is there any other kind? - is put to full, thrilling use and for a moment, Jurassic World recalls that feeling of awe which rooted the original so firmly in the collective cultural memory. It's when the movie has to get down to the nitty gritty of telling an actual story, with logic and characters and other such troublesome distractions, that it starts to go off the rails. Chris Pratt may be an immediately charming presence, but doesn't have the idiosyncratic charisma of a Jeff Goldblum, the gravitas of a Richard Attenborough, or the everyman authority of a Sam Neill. He's hamstrung by material which forces him to recite a series of leaden gags in lieu of developing an actual character, while his repeated assertions of manliness come off as juvenile posturing.

Speaking of which, the movie's antiquated representation of gender has been the subject of criticism ever since the first clip from the movie was released. Unfortunately, far from being taken out of context, as Trevorrow suggested, the female roles are arguably even more retrograde than first imagined. This doesn't appear to be down to anything more malicious than the same clichéd writing which also wedges a needless and shorthand-y divorce subplot between the two young brothers acting as audience surrogates in the first act, but even writing as someone who is generally reluctant to apply outside politics to any form of storytelling, World's female characters are punished and diminished in the presence of the male characters, themselves exclusively drawn from stereotypical masculine archetypes. Dallas Howard's Claire isn't much more than a stiff for Chris Pratt's self-identified 'alpha' to wear down, and the one time she asserts herself, it's to tell a nerdy male character to 'be a man and do something'. Meanwhile, Vincent D'Onofrio's Vic is so outwardly villainous and one-note that the only surprise is him not getting a chance to do his own Dr. Evil laugh. Oh, and did I mention that the person subject to the prolonged death described earlier was a working woman? Read into that as much or as little as you will.

Fortunately, the action is strong enough to offset the tedious emptiness of the movie's human characters. The absence of one well-developed character does rob the movie of any tension, with the bloodlessness only adding to the impression they're no more real than the CGI creations swirling around them, but that innate dinosaur appeal is a powerful thing indeed. Despite the movie's snarky in-jokes about audiences becoming increasingly blasé in their demands for bigger and better, there's still a childlike joy in watching raptors on the hunt, pterodactyls in mid-flight, or the lumbering beauty of a diplodocus grazing peacefully in a verdant savannah. The movie's respect for its creatures and concern over humans' treatment and commodification of animals, makes for one of its few poignant thematic successes, even if it all goes a bit wrong when it starts fully anthropomorphising them for the sake of a staggeringly stupid final act: this is a very dumb movie for the most part, even in a series where plot holes are a longstanding tradition, but the climax really takes the cake in throwing all semblance of reality and logical behaviour to the wind.

Jurassic World's faults are those that might be expected from a movie which has emerged from over a decade in development hell. It seems to be trying to tell three stories at once, of which only the spectacle truly delivers. The original sketched its characters just delicately enough to allow its magnetic cast to do the rest. World overburdens its characters with contrived histories delivered through hilariously inane anecdotes which just so happen to offer inspirational messages perfectly suited to each moment of peril ('Remember when we went on that date?'/'Remember when I had that dog?'/'Remember when...' [and I'm not even joking here] '...we saw that ghost?'). It delivers well enough on its core requirements as a summer blockbuster tentpole that few will come out feeling as though they haven't basically seen the dinosaur extravaganza they were promised, but the constant nods back to Jurassic Park only serve as a reminder of how much better rounded that movie was in the small details which gave its action meaning and heft and connection. Like World, Park for the most part worked better in individual scenes than as a complete picture, but it's those details which made Park's scenes so jaw-dropping and are conspicuously absent here. Financial success makes a fourth sequel an inevitability, but when Jurassic Galaxy rolls around in a few years' time, let's hope it remembers to bring back the soul so missing in World's impressive but hollow spectacle.

[Review] San Andreas

Before watching San Andreas, I was curious to know how long it has been since the last genuine, unabashed big-budget disaster movie. Naturally, this meant the first port of call was the filmography of Roland Emmerich, the German director behind Independence Day and The Day After Tomorrow, whose career is virtually name-associated with the genre. As it turns out, his last true disaster movie (not to be confused with disastrous movies, of which he's released a couple since) was 2012 in, weirdly, 2009.

That was one year after the release of Iron Man, the movie which turned Marvel and the superhero movie into the face of the modern blockbuster. Given the mind-boggling destruction which the average comic book movie trades in - see Avengers: Age Of Ultron, or if you haven't by this point, don't bother - it's no surprise that the disaster movie has since fallen by the wayside. San Andreas feels like a throwback in that respect, but also very much conscious of the changing tastes of the time.

[youtube id="hnJPHYAlid8"]

San Andreas

Director: Brad Peyton

Rating: PG-13

Release Date: May 28th, 2015

Dwayne Johnson, aka The Rock, as anyone who ever had a childhood will know him, plays a helicopter rescue pilot who sets out to reunite his family when the biggest earthquake in human history hits California as a result of the San Andreas fault starting to shift. There's approximately nothing more to the plot than that. That's far from a criticism, however, as simplicity is a much undervalued quality at a time when every new release seems to burden itself with increasingly convoluted world-building and sequel-seeding. San Andreas tells a straightforward story, going from A to B without any deviations along the way, then ends with an actual conclusion. It's one of the genre's strengths and, at the present time, a welcome relief from the norm.

If you've watched the trailer - see above - you know what to expect. Buildings collapse, people run and scream, the hero overcomes a personal trauma to save the day, and a fulsome female lead runs around in a wet vest. All boxes ticked. What makes the movie more distinct from its forebears is the presence of The Rock, who is quite unlike any disaster movie protagonist in living memory. The genre typically trades in everyman heroes, rising above their own shortcomings to survive, often with the assistance of a team, an onslaught by the overwhelming power of mother nature. One look at The Rock tells you that's not going to be the case here. Trying to pass off a 6'3 former wrestler as an everyman isn't going to work, and it's interesting how his physique alters the fundamental dynamic of the relationship between the genre and its protagonist.

Unlike disaster movies past, San Andreas' protagonist is never the one in danger. At worst, there are instances where he looks a mite concerned, but he exists almost entirely beyond the reach of the disaster itself. It's his daughter, played by Alexandra Daddario (required to do nothing but be sweet and look attractive, tasks she rises to meet triumphantly), who is the one caught in the chaos and finding herself, along with a bland English boyfriend-in-waiting and his sarcastic younger brother, perpetually trapped under collapsing buildings and rooms rapidly filling with water. His ex-wife, played by Carla Gugino, momentarily finds herself in similar trouble, but is soon rescued to join Mr. The Rock for some relationship therapy as the entire West Coast of the United States crumbles around them.

The Rock's essential invulnerability gives San Andreas something of the superhero movie vibe. Surprisingly, this works quite effectively. One of the genre's biggest obstacles is that it needs to go bigger each time in order to retain the level of awe-inspiring visual spectacle on which it overwhelmingly relies for its entertainment value, yet as the likes of Avengers proves, there's a point at which wanton destruction becomes so ludicrous that it's hard to care anymore. With Mr. The Rock (his 'character' has a name, but it's not important since he's basically The Rock in a differently coloured tight shirt) effectively watching the catastrophe unfold in the same way as the audience, he becomes one of the genre's more effective surrogate characters in recent memory. This also makes his family drama with Gugino's Ex-Mrs. The Rock slightly more relatable, helped by the two actors playing it with a unexpected amount of sincerity.

What also works is that the movie doesn't shy away from the human cost of such a massive disaster. There are a handful of shots whose sole function seems to be showing people being wantonly taken out by falling debris and collapsing structures, which is perhaps a little tasteless (although if that's your main concern, you're watching the wrong genre) but also gives the destruction a palpable sense of weight and loss. It's not enough to redeem the tiresomely uncanny valley-ish CGI depictions of cities being swallowed, enflamed and/or flooded, but that commitment to showing the arbitrary cruelty of its disaster demonstrates a rare and admirable strength of conviction.

Existing entirely outside The Rock's immediate vicinity is Paul Giamatti's seismologist, whose character's name also feels unimportant since he's basically the stock Voice Of Authority Played By A Respected Character Actor. It's nevertheless odd how tangential to the story he is, even by the genre's standards, not sharing a single scene or communication with the three leads. He gets to run away from one disaster - saving a little girl and watching his ethnic minority colleague be sacrificed in a scene which leaves no cliché unturned - shortly and with no small sense of irony after predicting the inevitability of such an event, after which he's stuck delivering grave warnings into a television camera. While such roles are part and parcel of the genre, the time spent in his character's company feels very much like time-wasting (other than, perhaps, to dispel the myth that the best course of action in an earthquake should be to hide in a doorway, when under a table is in fact the better course of action), an impressive feat for a movie coming in under 2hrs long. I should probably post an image of Mr. Giamatti at this point, but if we're honest, I think if we'd all rather see Alexandra Daddario, so let's go with her.

While Giamatti's scenes are strictly disposable, conveying information which could just as easily by offered through radio broadcasts or other background noise, it's to San Andreas' credit that it otherwise cuts to the chase when it comes to reaching the big events that audiences will be paying to see. There's approximately no time for such inconveniences as logic, but again, if that's your concern then the genre is most definitely not right for you. Stuff happens entirely to fulfil audience expectations rather than real world, or even internal logic, and that's not a bad way to go about approaching this kind of material. The Rock has a singular goal, to reunite his family, and despite being a rescue pilot who has commandeered a helicopter at a time when one would assume all airborne vehicles to be invaluable rescue resources, has absolutely no interest in helping anyone other than two specific women, who rather helpfully, are the only two people he really comes across anyway. In one amusing scene, his ex-wife (who has, inexplicably, been lunching with Kylie Minogue) happens to be the very first person he sees upon flying into Los Angeles.

It's lightweight, disposable fare, easy to mindlessly absorb with friends and laugh about afterwards. As a genre turn, it's a perfectly solid one, occasionally edging towards poignance with its willingness to engage ideas of loss on both personal and wider scales. Despite the big budget, it's nevertheless difficult not to see its self-aware campiness as having been undercut to a large extent by the likes of Sharknado, itself even more unrestrained in its audience-pleasing ridiculousness. The Rock proves he can do solid work without the safety net of irony, nicely underplaying a protagonist whom audiences are expected to take at least somewhat seriously despite the events surrounding him. Gugino and Daddario are entirely serviceable in their limited parts and Ioan Gruffudd is suitably slimy as Ex-Mrs. The Rock's new husband, whose evilness is defined by his riches in a movie produced, directed, written by and starring presumably very rich people. Make of that what you will. Regardless, San Andreas is decent enough multiplex filler, a throwback with just enough tweaks to keep it interesting, if never exactly engaging. It's not exactly good, per se, but far from a disaster.

[Review] Spy

After achieving stardom with her standout performance in Bridesmaids, Melissa McCarthy has become a divisive figure, at once a reliable box-office draw while being frequently accused of only being able to play one type of character and one style of comedy. Spy is her third collaboration with director Paul Feig, for whom she will also be headlining the female version of Ghostbusters in 2016. Her work with Feig has generally coincided with her best reviews, with the pair sharing a fondness for subversive, proto-feminist genre spoofs.

Those who have found McCarthy's schtick offputting in the past won't find much to win them round in Spy, an uneven but occasionally amusing bounce through the familiar stable of spy movie clichés. McCarthy's character, Susan Cooper, certainly fits comfortably into the actress' pantheon, exhibiting the expected reliance on pratfalls and foul-mouthed tirades that both fans and detractors have come to expect. What elevates Cooper above the likes of Tammy Banks, of the dreadful eponymous 2014 vehicle which deservedly earnt McCarthy many of her worst notices, is a willingness to allow McCarthy to explore a more outwardly vulnerable, yet secretly competent, side to her familiar persona.

[youtube id="mAqxH0IAPQI"]

Spy

Director: Paul Feig

Rating: R

Release Date: June 5th, 2015

As would appear to be the case with the upcoming Ghostbusters, and was to an extent also true of the previous Feig-McCarthy team-up, The Heat, Spy's most noteworthy trick of genre subversion is casting women in roles typically occupied by men. This idea drives the narrative more than might be expected. Cooper starts out as a highly skilled if unconfident CIA analyst, whose job is to support superspy Bradley Fine (Jude Law) via earpiece with all the information he needs to know to complete his missions, while she watches from the safety of her desk via camera and satellite feeds. When Fine and all the CIA's other agents are compromised, Cooper, the only agent unknown to the enemy, is sent out into the field by her boss (Allison Janney) to retrieve a nuclear weapon before Rayna Boyanov, daughter to a deceased supervillain, can sell it on the black market.

The idea of women taking over a traditionally male game is a rich one, but Spy doesn't offer as much of an original take on the genre as hoped. The movie ventures little towards exploring what unique approaches and challenges a woman, especially a 'plus-sized' woman, might face in the field - the only exception being Cooper having to fend off the advances of Peter Serafinowicz's lecherous Italian agent, which is never as funny as the movie seems to think it is and Peter Serafinowicz seems mildly embarrassed to involved. The female friendship angle is fun and affectionate, but has limited impact on the main plot beyond bringing hero and villain together. Instead, the same spy tropes which have provided easy fodder for spoofs since the James Bond phenomenon came into being in the mid-sixties are dusted off for another airing, even if most of them have long since been left behind in the genre's modern iterations and were already more effectively and lovingly sent up in the first Austin Powers movie. Cooper's competence is very welcome, encouraging viewers to laugh with rather than at, but has been an integral part of creating a likeable goofball spy ever since, to a less obvious extent, Get Smart.

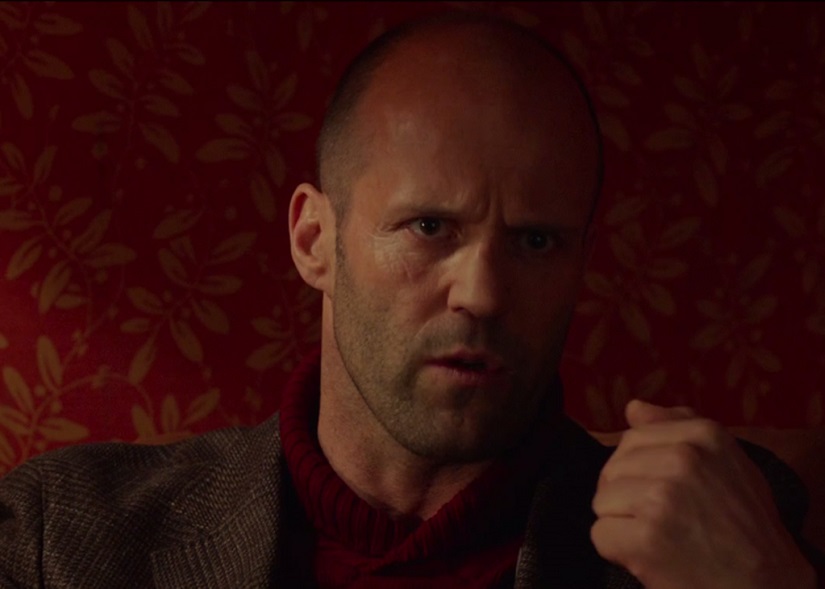

The presence of women in the lead roles does give the movie a novelty value on which it cruises for a while, albeit one which is more the result of the spy genre's near total absence of diversity in its leads than anything much this movie in particular has to say beyond noticing it. Like Kingsman: The Secret Service, the movie promises an anarchic, progressive spin on a typically very conservative enterprise, this time focusing on gender rather than class, but lacks the strength of its convictions to allow its non-traditional protagonist to display anything more unique to them than the standard heroic traits. In fact, it's Jason Statham's Rick Ford who offers the funniest, most determinedly radical spin on the action hero archetype. The character exaggerates Statham's persona by a factor of ten, resulting in a deranged, hyper-masculine doofus with total confidence in his own ridiculous abilities and contempt for anyone, especially women, barging in on his territory. Statham's performances have always carried an undercurrent of self-parody, so it's no surprise to see him shine when given his first chance to play unabashedly comedic material.

That's not to suggest the women fare at all badly: McCarthy is perfectly likeable as Cooper, whose lack of self-belief and frustration at being stuck behind a desk make it all the funnier and more engaging when she's finally allowed to break free of her shackles and start tearing things up. Where a previous McCarthy character threatening to chop a henchman's dick off and stick it to his head (thus making him, to quote, a 'limp-dick unicorn') would've relied on nothing but abrasiveness to get the laugh, here there's a palpable sense of relief as Cooper finally finds the freedom to fully express herself without reservation. Rose Byrne's clipped, arrogant Rayna makes a terrific foil, and her double act with McCarthy allows for some of the movie's most memorable, often seemingly improvised, exchanges. Miranda Hart, likely less familiar to US audiences than UK ones, also does solid work as Cooper's gawky co-worker and best friend, Nancy.

Feig directs with a sure enough hand and shows a reasonable aptitude for action, especially in a one-on-one knife fight in the final act, but there's never any sense of him stretching himself or going the extra distance to give the movie any sort of visual identity of its own. Perhaps symptomatically of the material, his work is functional and fit for purpose, but utterly unremarkable in all respects bar giving McCarthy the freedom to improvise some sparky one-liners into an otherwise drab script, and on the negative side, not immediately vetoing Jude Law's dismal attempt at an American accent, presumably put in place upon realising that three of the five main CIA characters were being played by Brits.

Spy doesn't break as much new ground as it thinks it does when it comes to spy spoofs, and the lack of substance behind its gender-swapping conceit doesn't bode especially well for Feig's Ghostbusters reboot. It is, however, sufficiently lightweight and amiable to be a serviceable diversion at a time when the quality of big screen comedy has taken a slide when compared to that on television. The nuances added to McCarthy's character allow the actress to bring some depth and pathos to her confrontational persona, even if it's Jason Statham's balls-out lunacy which ends up stealing the show as one of the few genuinely surprising and chaotic elements in an otherwise entirely forgettable affair.