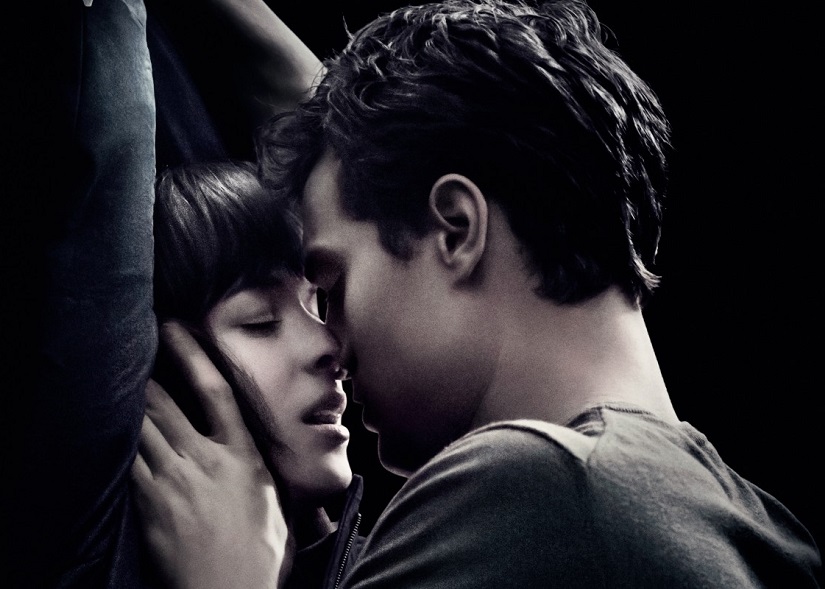

[Review] Fifty Shades of Grey

I knew very little about Fifty Shades Of Grey going into the movie, other than it being about BDSM and that the book's prose was the subject of widespread derision. The latter point always seemed an odd one to me: reading erotica for the prose sounds a bit like watching porn for the art direction. It exemplifies an attitude of snobbishness which continues to permeate criticism of the arts in all media. By most accounts, plenty of women found the book an entirely pleasurable experience. It must have been doing something right.

As you've probably worked out by now, that kind of introduction is only heading in one direction, so I'll just out and say it: look past the upturned noses and Fifty Shades Of Grey is not only a perfectly decent movie, but wittier and more subversive than many would have anticipated.

[youtube id="SfZWFDs0LxA"]

Fifty Shades Of Grey

Director: Sam Taylor-Johnson

Rating: R

Release Date: February 14, 2015

Were you expecting a bodice-ripping, dick-swinging, ass-pounding, ball-squeezing, face-sitting, vaginal-fisting extravangza, Fifty Shades is not it. The fact the movie made it to cinemas should have told you that much, and besides, in the event of disappointment, there's always YouPorn. Though there's a cursory amount of whipping, some tied hands and quite a bit of moaning, director Sam Taylor-Johnson consciously shifts away from anything resembling exploitation. It is best described as a sex-themed character drama, more concerned with subverting screen representations of male and female sexuality, when they exist at all, than utilising them for blunt titillation. There's a reasonable amount of sex, but artfully shot and with one eye clearly aimed at meeting the requirements of the R rating. Only Anastasia shows anything provocative, though given how close a few of cuts are to Christian's crotch, the feeling pervades that this is more the result of institutional sexism at the certification boards rather than willing self-censorship.

Even so, the flashes of pubic hair from both lead characters feels satisfyingly liberated compared to the sterility afflicting your average blockbuster. The imbalance in what the movie is allowed to show does have the side-effect of slightly shifting the movie's gaze towards Anastasia rather than Christian, where it should be, but this is nevertheless the rare movie which emphasizes female pleasure first and foremost. True, it's mostly through bitten lips and sensual gasps, but remains a heck of a lot better than anything else Hollywood has provided in recent decades. Fears about Anastasia's position as the submissive in the relationship are also ill-founded: consent is not only a key concern for Christian, but to such an extent that it almost circles around to satirising the challenges of tackling that topic in real-life. Ana's distaste for the consent contract which Christian is desperate for her to sign can't help but nudge, if accidentally, towards the inherent hypocrises of 'yes means yes' laws.

The fact Fifty Shades is the rare Hollywood movie where the entire creative team is female makes its even-handed treatment of gender and sexual expectations all the more poignant. This is a movie where a woman inhibited by her sexual shame meets a man imprisoned by his and through pushing the limits of their sexual and emotional horizons, begin unearthing each other's buried humanity. Dakota Johnson is a revelation as the meek but quietly intelligent Ana, bringing considerable pathos and underlying strength to the role as the character gradually learns to assert herself in bringing her relationship with Christian onto her terms even while acting as his submissive. The movie may offer the tamest possible representation of BDSM, but understands the seemingly contradictory principles at its core (pleasure through pain, liberation through abandonment of control) and neatly weaves them into its character arcs. It may not be particularly subtle, but it works.

As Christian, Jamie Dornan struggles to make much of an impact beyond, to judge by the panting admiration of the girls sitting behind me, the not inconsiderable appeal of his toned body. Christian is tormented by his obsession with control and how Ana challenges his refusal to engage with women on anything other than the terms of a contractually defined relationship. Dornan is a little too baby-faced and young to authentically sell the character's depth of sadness and anger, leading to his brooding seeming a little too practiced and pouting to make his inner turmoil completely believable. Were the movie more geared towards the mostly implied eroticism, his aesthetic appeal would be more than enough. With emphasis instead placed on the character drama, his struggles make Christian more frustrating than enigmatic and restrain - and not in the fun way - his chemistry with Dakota Johnson.

Also frustrating is the movie's status as the first entry in a planned trilogy. After a lively opening, the pace drags considerably during the middle act with a few too many repeated 'why don't you let me in' conversations and family drama which emphasizes Ana's homespun nature but gets mighty tedious while doing so. The cliffhanger that concludes the movie, while an important moment for Ana, feels like it should have arrived at roughly the halfway or three-quarter point rather than being spun out into an entirely unsatisfactory ending (reaction of the girls behind me: "What? Is that it?"). It's even more of a shame because the movie cuts off just as both characters seem on the verge of a breakthrough without having quite crossed the threshold. A dinner-slash-business meeting between Ana and Christian, wonderfully lit in lurid orange, marks the beginning of the final act and is a noteworthy highlight for finding the perfect balance between tension, humour and engaging character work.

That the movie never quite finds that level of cohension again is a shame, because its individual elements are played with unexpected consideration and, occasionally, tenderness. It's easy to see why the story has connected so strongly with such a large audience, bringing together as it does the essential clichés of arguably the two most widely beloved female-appealing stories - Cinderella's prince and the ingenue dynamic, plus Pride & Prejudice's reserved, Byronic love interest - and twisting them into something at once dark but modern, open-minded and gently empowering. Sure, you can criticise the unmemorable dialogue (sadly, only one 'holy cow!' and not a single 'oh jeez!'), the repetition of several narrative beats, cheesy use of soundtrack and a meandering middle act, but submit yourself without inhibitions and you may be surprised how much you enjoy the experience.

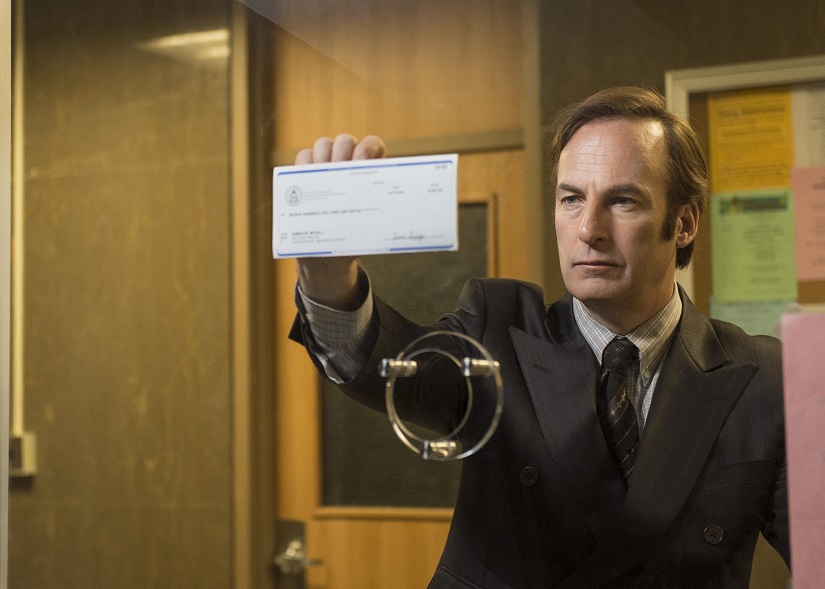

[This Week In TV] Better Call Saul, Law & Order SVU, Constantine, Wheel Of Time

This Week in TV is a new weekly feature reviewing the best, worst and most interesting episodes of television from the past seven days. The plan is to cover a wide variety of shows, but not always the same ones each week, so let us know in the comments which ones you’d particularly like to read about. This week takes in the two episodes marking Better Call Saul's series debut, Law & Order SVU's take on the Gamergate controversy, Constantine's season finale and a Wheel Of Time pilot made and released under inauspicious circumstances and starring Billy Zane, as though things weren't bad enough already.

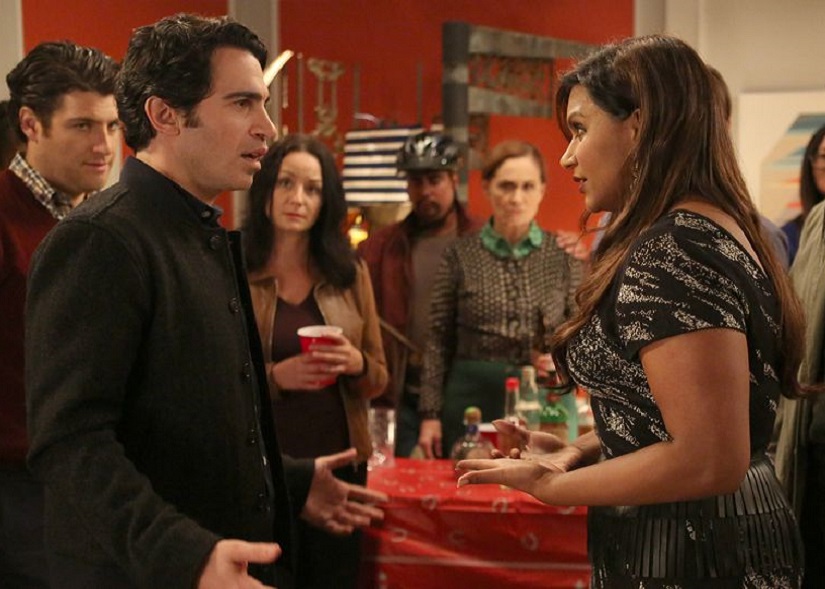

[This Week In TV] Jane The Virgin, Broad City, New Girl, The Mindy Project

This Week in TV is a new weekly feature reviewing the best, worst and most interesting episodes of television from the past seven days. The plan is to cover a wide variety of shows, but not always the same ones each week, so let us know in the comments which ones you’d particularly like to read about. This week takes a look at the ladies in television, starting with a big reveal on Jane The Virgin, a strap-on standoff in Broad City, Jess trying to save a disastrous business pitch in New Girl and big moves in The Mindy Project.

Jane The Virgin - "Chapter Twelve". Jane The Virgin has been this season's critical darling since its debut last October, another triumph for the CW in its expanding library of strong genre programming. Jane's near perfectly balanced blend of melodrama, comedy and pathos came out of the gate fully formed and making an instant star of lead actress Gina Rodriguez, whose performances have infused the sharp writing with soul and sweetness. Twelve episodes in and there's no signs of slowing down: Rodriguez's Jane remains far and away the most huggable person on television, while each episode somehow manages to pack in moments of sincere, heartfelt sweetness alongside a cavalcade of increasingly loopy plot developments. The news last week that Jane was to become a writer for a telenovela threatened to be a little too cute for its own good, but worked perfectly in the context of this episode: she's delighted to be offered the chance to write an episode of her own, but less so when it is revealed she was only chosen because no-one else was willing to write a death scene for diva-ish star Rogelio, who is also Jane's father.

Jane's struggles to write Rogelio's big death scene at the end of her episode meant a fun little jaunt through the series' main themes. Having her take inspiration from a moving act of forgiveness from her grandmother was a perfect resolution for a show which has always put family and empathy front and centre, but the realisation that making the scene sing meant embracing the spirit of the telenovela was no less important. That spirit is what has given Jane its identity and the acknowledgment felt like the writers giving a nod to the fact they know exactly what their show's strengths are and how to play to them. That decision also informed the big reveal of Sin Rostro's identity, which played out in the most deliciously ludicrous manner as Rose drowned Emilio in cement - a pretty nasty way to go, all things considered, but finding just the right application of camp to stay on the right side of nastiness. The same was true of the fantastic pre-commercial scene of Milos seemingly slitting Petra's throat, a twist so shocking it went full circle into hilariousness, only to be revealed as a ruse to prove Magda was faking her disability.

While I still feel that Jane's hyper-condensed plotting can get a little exhausting over a full hour - two half-hours per week might be a better fit - the show continues to demonstrate such a masterful command of tone and momentum, not to mention a cast impossibly adept at making the comedy and drama work in tandem without cancelling each other out, that it is rarely anything less than a delight.

Broad City - "Knockoffs". Broad City boggles the mind in the best possible way, because even at a time when Archer and Rick & Morty exist, it still manages to go places you could never in a million years imagine a television show - a live-action one, no less - getting away with, especially when committing to its filthiness with such unrestrained delight. A comparison between the doe-eyed Jane The Virgin and a show as bawdy as this may seem a tad misguided on the surface considering the, erm, contrasting nature of the material, but there's a definite similarity in what allows the two shows to get away with what they do: in Jane's world, the craziness of the plotting; in Broad City, being able to dedicate an episode's main plotline to strap-on sex and one man's devotion to his personalised, ethically sourced green dildo.

Both shows, at their heart, are about family and friendship. Ilana and Abbi may be trashier, louder and more clumsily hopeless at everyday existence than Jane's open-hearted clan, but it's their unconditional support and affection for each other which keeps Broad City charming. Take, for instance, the strap-on plotline. A lesser show would likely make fun of Jeremy for his kinks or Abbi for her discomfort, but Broad City actively celebrates that weirdness, a spirit hysterically embodied by Ilana's dance of joy at discovering Abbi's situation. Make no mistake, it's very, very funny stuff, especially the For Your Eyes Only-riffing shot between Abbi's legs of the dildo dangling down over a delighted Jeremy, but there's a sincere sense of love at the idea of two people pushing the boundaries of their sexuality. That positivity is what fuels and humanises the comedy, appreciating the fact people can be into to some pretty unexpected stuff, but that's OK because it's what makes them who they are. The argument which broke Abbi and Jeremy up may have seen Jeremy act like a bit of a dick (I know, I know) over the specifics of his kink, but there's no sense of finger-pointing because it had already been established how important it was to him.

Meanwhile, Ilana and her mother's B-plot was pretty much just a series of ridiculous events - from collecting knock-off handbags in a sewer to being arrested en-route to a funeral - but punctuated with some great gags, from the pair's inherited similarities - vigorously shaking the nail polish in unison - to Bob Balaban's flustered turn as Ilana's dad. It's a terrific sequence that may not have much substance behind it, but worked as a hilarious insight into a day out with a particularly eccentric family.

New Girl - "Swuit". 'Swuit' isn't an especially funny episode of New Girl, but does demonstrate that after a disappointing third season in which overcomplicated plotting and tedious romantic complications weighed heavily on the show's lightness of touch, showrunner Elizabeth Meriweather has managed to get things back on track by returning to the simple comic formula of the first two seasons even if the jokes don't always land as precisely as they should. The show's greatest strength is in bouncing the loft's four utterly ridiculous personalities off each other under increasingly fraught circumstances. Pairing them up resulted in those personalities being shackled by having to work as part of a credible couple, particularly as the cast's comedic straight men have been provided almost exclusively by supporting characters such as the ever-incredulous Cece - huge shout-out here to Hannah Simone for what must be one of the funniest range of aghast expressions on television. It's the fact that the five main characters are so completely useless at working together, but try so hard anyway, that has been at the heart of many of New Girl's funniest episodes.

In that respect, 'Swuit' should've been onto a winner in focusing on Nick and Schmidt's attempts to come up with a business plan together under the pressure of an impending deadline pitch. For all that it's possible to analyse everything down to the most minute detail, the simple truth is that sometimes the jokes just don't quite hit even when they probably read fantastically well on paper. Nick and Schmidt shouting lovely things at Jess was never much more than mildly amusing, despite being an appropriate reaction on a character level for two furious people who nevertheless appreciate their friend's good intentions. The stammering pitch to Lori Greiner started well, but faded once the joke's single dimension wore thin. Winston and Coach investing in Cece's future up until discovering that future would be built on an arts degree was pretty funny - especially the course professor's resigned despair at his lot in life - but never quite found the spark to really take off. Regardless, that 'Swuit' proved one of the weaker episode in recent weeks is testament to how well New Girl has stabilised itself after last season's near-collapse.

The Mindy Project - "No More Mr. Noishe Guy". All cards on the table, I'd never watched The Mindy Project before this week, but with all of this article's shows having a somewhat feminine bias, thought I'd fully commit to the idea by taking a look at a show which seems to have grown in popularity and appreciation over the past few seasons. As a first time viewer, it's easy to pick out the elements which likely inspired that creative revival: Mindy Kaling is a perfectly likeable presence at the centre of the show, with a similar set of core characteristics - professional competence masking a scatterbrained personal life, devotion to food, lack of appreciation from her colleagues - to the late, great Liz Lemon. The overall tenor of the show is more low-key in its zaniness than 30 Rock or Parks & Recreation, but shares an appreciation for offhand silliness, whether delivered via a quick-one liner or a visual gag like a rat-infested brownstone.

The problem is that while low-key is fine, it here led to everything feeling strangely subdued. On the evidence of 'No More Mr. Noishe Guy', the more outlandish quips felt somewhat at odds with a mood that would seem better suited to more dry, subtle humour than Mindy being mistaken for Malala Yousafzai - which, admittedly, is supposedly based something Kaling experienced in real life - or getting all her medical treatments done at once. The quirks of Mindy the character also seem a little too indebted to Liz Lemon, but struggled to integrate as well in a character played relatively straight. The show broadly felt more geared towards its dramatic elements, which included an effectively played thoroughfare about having to adapt to life taking major turns out of the blue, than its comedic ones, which tended to come in fits and starts. Obviously as someone coming in at what is a major turning point of the season, with one character leaving the show and a pregnancy revelation throwing Mindy's life into further disarray, there are undoubtedly plenty of nuances which will have passed me by - hopefully the personalities of the non-Mindy characters feel more distinct with the benefit of long-term viewing, for instance. The show seems perfectly agreeable, but with Broad City, New Girl and Parks & Rec leading the line and 30 Rock still fresh in memory, a distinctly disposable entry in the resurgent field of female-led comedy.

[Review] Kingsman: The Secret Service

Director Matthew Vaughn and screenwriter Jane Goldman's working relationship has to date produced four movies, three based on comic books, all of which have offered a similar set of strengths and flaws. Kingsman: The Secret Service is the latest off the production line and the most succinct review I can offer is that if you enjoyed Kick-Ass and X-Men: First Class, you'll almost certainly enjoy this as well. Kingsman shares Kick-Ass' genre-spoofing premise, this time taking on superspies rather than superheroes, and throws in First Class' training-montage-at-a-country-manor middle act for good measure. In fact, it might even be the same manor.

Like Kick-Ass, Kingsman is based on a Mark Millar comic and while his characteristically flippant rape scenes are mercifully absent, the same formula of ultraviolence, adolescent humour and non-stop referencing of beloved pop cultural artefacts applies. Here, a streetwise London kid named Eggsy (Taron Egerton) is recruited by superspy Harry Hart (Colin Firth) to join an undercover black ops organisation known as Kingsman, who pride themselves as much on their bespoke suits and impeccable manners as their efficiency in the field. After proving his worth in training, Eggsy finds himself embroiled in an international plot by lisping industrialist Richmond Valentine (Samuel L. Jackson) to exterminate the human race with smartphones. Really.

[youtube id="ijXYed0_kzA"]

Kingsman: The Secret Service

Director: Matthew Vaughn

Rating: R

Release Date: February 13th, 2015

The idea of a working class superspy is a fascinating one on paper, because the genre has for so long worshipfully adhered to the James Bond formula of a hero saving the world through judicious application of imperialist white privilege - even if non-Bond movies have rarely been as self-aware about their hero's faintly appalling nature. Whilst generally aiming for Bond throughout, the movie's first act ends up more closely mimicking The Avengers, the '60s British TV show rather than the Marvel comics. This isn't just down to Harry Hart's Steed-esque umbrella and immaculate tailoring, but the combination of an experienced and slightly rebellious old-school pro with an unconventional if talented partner. Firth is a delight as Hart, offering just enough of a twinkle in his eye above the stiff upper lip to bring out the character's humour without compromising his integrity or turning him into a caricature. Newcomer Taron Egerton makes a worthy foil, having enormous fun with Eggsy's council estate [Americans, read: projects] accent and incredulousness at the snooty entitlement of his fellow Kingsmen.

The early scenes in which Hart and Eggsy team up are the most enjoyable courtesy of the two stars bouncing off each other so well. Once they go their separate ways in the latter stages and Eggsy takes the lead, the movie loses track of itself and falls back too heavily on replicating the Bond formula without offering much personality of its own. Part of the reason the movie ultimately fails when it goes for the full Bond spoof is that Bond himself is so completely rooted in the imperial hero tradition that the only way Eggsy can only embody such a character is by abandoning much of the attitude which makes him unique. In the end, he's reduced to just another action hero in a suit shooting his way through identikit corridors - no majestic Ken Adam-esque sets here - with his success down to embracing the methods and mindset of his aristocratic peers rather than his own urban upbringing.

Like Kick-Ass, the movie mistakes referencing other material for subverting it. Hart is a cocktail of visual references, from Bond's suits to Steed's tricked out umbrella and Harry Palmer's glasses, with a throwaway quip about Maxwell Smart's shoe phone for fun. Taking a sophisticated spy down to a rough local pub is a fun spin on the exotic locales trope, but genuine wit tends to be the exception rather than the rule. A scene in which supervillain Valentine dines Hart with McDonalds is another, functioning both as a good joke on another overfamiliar genre scene and, perhaps unintentionally, the role of high-end product placement in such movies, but the lack of focus in its satire means even the best gags only really work in isolation.

Take Valentine, for instance: Sam Jackson has an absolute ball playing him, but for a movie supposedly parodying the genre's typical stuffiness and class assumptions, it's a little rich for the central villain to not only be a stereotypically boorish American, but a black man with a disability and a firm belief in the power of technology and the dangers of climate change. Despite Jackson's best efforts, the character never evolves beyond his tics and is played so firmly as a figure of fun that he never feels especially threatening or memorable. The opposite is true of his sidekick, Gazelle, a beautiful henchwoman with razor-sharp blades for legs and a penchant for deadly breakdancing. She may be an unreformed Bondian villainess, a killing machine with a fabulously outré weapon, but Sofia Boutella gives her a hint of personality in her sneering attitude and relationship to Valentine that allows her to become that much more fun and engaging. She certainly fares better than the only other noteworthy female character in the movie, fellow Kingsman recruit Roxanne, whose sole purpose for existing seems to be filling the role of sympathetic female and doesn't even get to kiss the hero.

The movie works better as an actioner than a comedy, moving at a decent clip throughout and with an extraordinarily staged fight in a church as its centrepiece, albeit one almost ruined by Vaughn's decision to give his action sequences the air of a judderingly overedited music video by messing with the camera shutter speeds. It's nevertheless a consistently fun watch, even if that inability to form a coherent tone prevents it from making the most of its strengths. It's not funny enough as a comedy, but too frivolous and bloodless to fully sell its stakes as an action movie. It's consistently fun, but so lightweight you'll have a hard time remembering anything about it afterwards bar the overfamiliar references. In other words, it's exactly what you'd expect from a Jane Goldman screenplay.

It certainly has its charms, from Mark Strong being a perfect choice as the Q figure, Michael Caine doing his Michael Caine thing - though he's an odd choice for the head of the upper-crust Kingsman, given that famous South London accent - to an enjoyable Mark Hammill cameo. Its final gag won't sit at all well with feminists, but is appropriately and amusingly vulgar for Eggsy's character and a good joke at the expense of the endings of Roger Moore Bond movies. The Savile Row suits are exquisite, the highlight of the movie if you like that sort of thing, and one area where the movie gets a leg up on Bond (steady) and his recent, ill-advised fling with Tom Ford's unseemly excuse for tailoring. It's probably the lesser entry in the Vaughn-Goldman quartet, though they're so broadly uniform in quality that the differences are largely negligible. In other words, it all comes back to that succinct review from the introductory paragraph: if you liked Kick-Ass, you'll probably like this too.

[This Week In TV] Fortitude, The Big Bang Theory, The Americans, The Simpsons

This Week in TV is a new weekly feature reviewing the best, worst and most interesting episodes of television from the past seven days. The plan is to cover a wide variety of shows, but not always the same ones each week, so let us know in the comments which ones you’d particularly like to read about. This week sees icy whodunnit Fortitude debut with a feature-length episode, the first episode of The Big Bang Theory of 2015, The Americans kicking off its third season in timely fashion and Elon Musk taking over The Simpsons.

Fortitude - "Episode 1". Fortitude, a $25 million series from British channel Sky Atlantic, marks a fairly transparent attempt at edging in on the popularity of the Scandinavian crime thriller. The show follows various key members of the community of a small town in the Arctic where the old mining industries are dying out and the mayor is pushing to commence construction on a hotel to boost local tourism. As we are reminded quite regularly, Fortitude is a town where people only come to work, so everyone has a job and therefore there is no poverty and no crime. It is, the governor says, the safest place on earth, which doesn't exactly explain why it has such a large and well-funded police force. It also neglects the strong possibility of polar bear attack, which means every citizen must be armed with a hunting rifle at all times.

Fortitude has such a large and starry cast that even over its two-hour premiere it struggles to give many of them enough time to establish themselves. Sheriff Dan Andersson (Richard Dormer), governor Hildur Odegard (Sofie Gråbøl) and the Sutter family are given a solid amount of screentime, but everyone else is forced to make do with a handful of scenes at most. Luke Treadaway's young scientist Vincent at first appears to be the audience surrogate, as we see him being shown around Fortitude by Christopher Eccleston's more experienced Professor Stoddard, but both characters soon vanish into the mix, as does Michael Gambon's tortured photographer, who appears in the first scene before largely vanishing. While life in the town is beautifully established on a visual level, with countless sweeping shots of icy tundras, its lack of attention to large swathes of its cast means it fails to establish why we should care about any of them on an emotional level. Each has a relevant point in their backstory which gets revealed, but there's little time to find the personality quirks or the humour to cement them as interesting individuals.

This means that when the murder finally occurs, the moment relies on the audience being shocked because of who the actor is rather than through any affiliation to the character. Only Stanley Tucci's DCI stands out in terms of personality, but that's more down to Tucci's naturally wry eccentricity than anything in the writing. It's also worth noting that he doesn't appear in the first hour at all and only midway through the second, at which point he effectively takes over the show completely. It's an untidy switch, but one which at least gives the show some focus. There are stuble hints of supernatural weirdness, such as the appearance of a pig in a hyperbaric chamber and a defrosting woolly mammoth carcass which may or may not have brought something to the surface with it, but these are restricted to enigmatic suggestions rather than made a key parts of the established mysteries. Fortitude has all the elements of a compelling mystery, but while its technical excellence cannot be denied, it could do with thawing out its personality a little more.

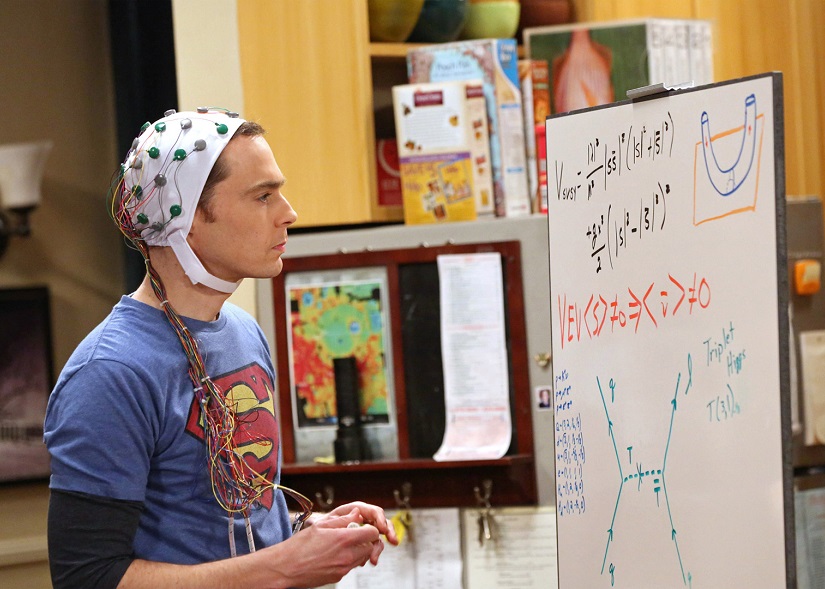

The Big Bang Theory - "The Anxiety Optimization". Big Bang attracts a lot of snobbery not only due to being an old-fashioned multi-camera sitcom with a laugh track, but an immensely succcessful one which was previously programmed against internet favourite Community. The truth is that while the show may too often go for the lazy gag or sometimes misjudge its tone, it is nevertheless an excellent example of the form which has worked hard over the past few years to meaningfully develop its central cast and iron out the more tedious habits from its early years. The addition of Amy Farrah Fowler (Mayim Bialik) and Bernadette (Melissa Rauch) to the cast in season four in particular forced the characters to emotionally mature beyond the one-dimensional stereotypes they initially were, leading to something of a creative renaissance over its three most recent seasons.

Unfortunately, that golden run has juddered to a halt in the show's eighth season, which has struggled to find anything meaningful to do with the latest round of character evolutions - Penny getting a stable job, Raj finding a girlfriend - and too often slipped into the old habit of laughing at its characters rather than with them. Howard and Bernadette's relationship seems to have particularly suffered: while Bernadette's characterisation as something of a nascent supervillain has been plentifully entertaining over the years, her stubbornness has recently edged into meanness in preying on her husband's insecurities. Similarly, Sheldon has always existed on the razor's edge between obliviousness and obnoxiousness, yet his treatment of pseudo-girlfriend Amy has this season felt uncomfortably one-sided and manipulative. The show is at its best when the cast feel like friends you'd want to hang out with for the evening, but affectionate mockery has tended this season to slip into unpleasant nastiness.

'The Anxiety Optimization' just about stays on the right side of the line with Howard's creation of the game 'Emily or Cinammon', which involves guessing whether a quote from Raj was said to or about his girlfriend or his dog. While it clearly frustrates Raj, there's no sense of malice to the teasing and embraces what makes the character unique rather than targeting it, thus providing a solid well of laughs even if the conclusion - with a rare appearance by the real Emily! - is weak. In the main plot, Sheldon struggles to get to grips with his new field of study and puts into practice a theory that anxiety makes people more productive, meaning his friends get the opportunity to rile him up a little bit. While not especially funny, the plotline is rooted in another recent character development for Sheldon - his uncertainty over changing his career path - which gives it enough emotional resonance to work. It also allows Leonard, Raj and Howard to make fun of him without undermining the revelation earlier in the season of Sheldon being fully aware of how difficult he can be as a roommate, but also struggling with how much the others make fun of him because of it. With half a season still to go, hopefully 'The Anxiety Optimization' marks a turning point back towards the affectionate, character-based humour which has been the bedrock of the show's best years.

(Also, Sheldon's a Swiftie now, so there's that.)

The Americans - "EST Men". The Americans evolved from a gripping if overly stoic show in its first season to one of the most sophisticated and compelling shows on television in its second. Much of that success was down to a greater balance being found between the two sides of the Jennings' lives, presenting the face of a typical happy American family on the surface while concealing their real identities as undercover Soviet agents. The show's dramatic stakes have increased in line with Philip and Elizabeth's inability to prevent one life from bleeding into the other, forcing them to scramble just to maintain their cover rather than, as is often the case in spy dramas, being shown as flawless experts in their field. Rather than emphasizing the characters' strengths, we have seen them steadily become more isolated and fearful over time, struggling with dictats from superiors ever more out of touch with reality on the ground and their own conflicting desires between keeping their children safe and indoctrinating them in an ideology which even they have begun to doubt.

'EST Men' sees the Centre solidifying its threats to force Philip and Elizabeth to begin the process which will ultimately see their secret identities revealed to their daughter, Paige, with the aim of bringing her into the fold as a second generation spy. The dinner over which these orders are relayed is an excellent demonstration of how effectively the show balances its family drama and spy thriller elements. The Jennings' relationship with their former handler, Gabriel (played by the great Frank Langella, sharing the screen for the first time with Matthew Rhys and Keri Russell), is warm and affectionate, right down to him playfully slapping away Philip's hand from trying to get an early taste of the main course. That affection is quickly revealed to be as dishonest and manipulative as the Jennings' friendship with their neighbour and FBI agent, Stan, whose home life is falling apart even as his department seems to be edging ever closer to identifying the Jennings' secret identities - particularly since Elizabeth just gave his supervisor a good look at her face before knocking him out with his own gun.

'EST Man' mostly comprises table-setting for drama to come, but there's no shortage of powerful moments that make it an engaging hour in its own right. The aforementioned dinner scene with Gabriel is outstanding, lending great symbolism to the earlier flashback to Elizabeth teaching Paige how to swim by throwing her into the deep-end of a pool. We also see how Elizabeth remains devoted to the party cause, having already laid the path for Paige's indoctrination ("We're getting her ready to find out who we really are") even while Philip remains profoundly opposed. Philip sacrificing Annelise is a nasty reminder of how people are reduced to nothing but pawns in the larger political game, making it all the more terrifying that he is now expected to bring his daughter into this life. The parallels between the Soviets' struggle in Afghanistan and the Americans' more recent conflict in the region is played a little too obviously, but 'EST Men' is an excellent start for The Americans' third season and an inauspicious hint for the Jennings that the screws are only going to get tighter from here on out.

The Simpsons - "The Musk That Fell To Earth". At this point, writing about how far The Simpsons has fallen from grace since its glory years feels like whipping the proverbial dead horse, or perhaps beating up the proverbial Krusty burglar. "The Musk That Fell To Earth", while utterly mediocre rather than offensively terrible, nevertheless provides a snapshot of where the series has gone so badly wrong in recent times - assuming 'recent' is a broad enough term to encompass a full fifteen years of creative collapse.

The episode sees the eponymous entrepreneur arrive in Springfield in a space shuttle following a pointless cold open in which the Simpsons attempt to trap a bald eagle which has been preying on their recently installed birdhouse. You'd think the omission of the traditional couch gag would be a positive sign that the story ahead was too tightly written to be cut down any further than absolutely necessary, but alas, such meandering continues throughout an episode whose sole aim seems to be indulging its guest star in the most shameless way possible. The best episodes of The Simpsons did not need especially deep or complex plotting to succeed, but were structured intelligently enough to build an escalating sense of comic momentum through cause and effect. Here, Musk turns up in his space shuttle, momentarily finds inspiration in Homer's dim-witted observations, teams up with Burns to turn Springfield into a futuristic, energy-efficient city (complete with Futurama tube-travel), is rejected after his ideas cost too much, then leaves. Each segment of the narrative is only loosely connected, often swapping character viewpoints to jarring effect, which prevents the gags from building on each other or feeling any more substantial than a series of non-sequiturs.

Considering the whole episode is devoted to Musk, he's such tedious presence that the show feels the need to call him out on it even while grovelling to his genius at every opportunity. The most memorable guest stars were those which used the actor's persona to offer a unique perspective on the characters and the world they live in. Here, as in most other cases where a guest has played themselves, the episode is requisitioned to promoting the its star's legend (and ego) rather than the other way around. The few gentle jibes directed at Musk are quickly qualified - yes, his ideas are insanely expensive and impractical in the short term, but that's society's fault for not being ready for his revolutionary brilliance! - and the episode's few laughs ("Oh god, it attracts women as well!") come from jokes which have little to do with the main 'plotline', to use an exceedingly generous term. "The Musk That Fell To Earth" may not deface the characters in the way the worst episodes have over the years, but its relentless pandering to its guest star is symptomatic of a show which has long since sold out its once thrillingly nonconformist identity.

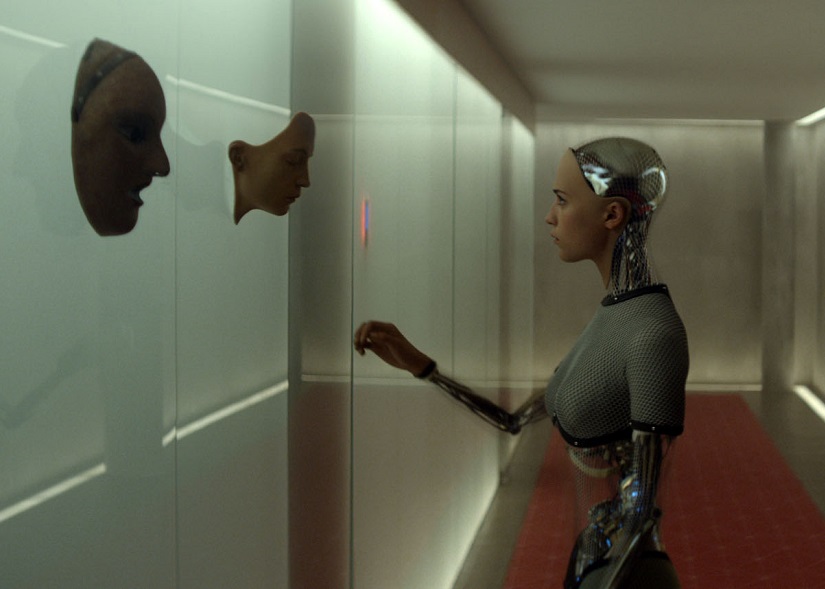

[Review] Ex Machina

Ever since Fritz Lang's Metropolis, female androids - or gynoids, to use the correct term - have been presented in cinematic science-fiction as a means of exploring man's conflicted relationship with female sexuality. Where Lang's 1927 opus dissected the impact of male fears on a religious and social level, Alex Garland's Ex Machina updates the story to a modern age where the fight for control over women's bodies has gone digital. The unsettling atmosphere which builds from the first meeting between Domhnall Gleeson's jittery tech nerd Caleb and the robotic Ava, constructed by Oscar Isaac's unstable Steve Jobs-alike Nathan, is as much down to the imbalance in control that the two men exert over Ava's existence as Garland's taut control of pace and tone.

Caleb is brought in by the reclusive Nathan to administer the Turing Test to Ava. However, since Caleb is aware of Ava being an AI from the start, Nathan posits that the real success will be if Caleb starts to regard her as a real person irrespective of that foreknowledge. Much of the drama unfolds through a series of conversations where Caleb increasingly feels as though it is he who is being tested, caught in the middle of a battle of wits between Nathan and his creation.

[youtube id="EoQuVnKhxaM"]

Ex Machina

Director: Alex Garland

Rating: R

Release Date: January 21, 2015 (UK)

As an effective three-hander - one other character features semi-regularly, but remains silent - the movie hinges on the performance of its leads to make the conversations as engaging as they need to be to sustain the drama. Of the three, it's Alicia Vikander's Ava who steals the show. It's hardly the first time we've seen this kind of performance in playing an AI - wide-eyed inquisitiveness, slightly inhuman movement, innocent demeanour - but Vikander ever so gently uses the body politics of the piece against its audience, using her character's awareness of her enforced passivity to inflect sadness and fear even while not playing them directly.

Ava's relationship with Caleb takes place entirely on either side of a glass screen and Vikander, with microscopic subtlety, evokes a sex worker talking to her client through a webcam, expressing desires and affections that can never quite be alluring enough to obscure the artifice of the performance. When she chooses to show Caleb what she would wear for him on a date, affecting a wig and a dress to conceal her transparent robotics, the scene carries a lingering sense of sadness that is reinforced with the sight later on of her undressing again, alone in the dark. Caleb later challenges Nathan over whether Ava was programmed to flirt with him, showing himself unable to distinguish between his outward anger at feeling manipulated and his inner frustration at being unable to indulge his fantasy that the object on the other side of the screen could be capable of sincere human intimacy. A late reveal about the parameters Nathan used in designing Ava only increases the underlying ugliness of the metaphor.

Oscar Isaac certainly gives Vikander a good run for her money. His Nathan is fearsome and mercurial, wracked by a genius-level intellect at once fuelling a self-image of a man on the verge of crossing the threshold into divinity, while stoking a barely suppressed paranoia about being destroyed by his creations, an internal psychological conflict he attempts to control through drink and violent exercise. Ava is his parallel: calm and controlled, intellectually curious but welcoming and engaging towards Caleb in lieu of Nathan's domineering idea of friendship. Domhnall Gleeson too is as captivating a screen presence as ever, hiding a calculating cunning behind Caleb's nebbish exterior.

Beyond its characters, the movie takes place exclusively in a single location, Nathan's uber-modern hideaway in the stunning Norwegian wilderness. Garland slowly transforms the idyllic locale into an automated prison, contrasting the natural but sombre light of the house's upper levels, where the boys eat and play with nature all around them, if once again behind protective screens, with the windowless lower floors, where Nathan's research takes place under the sterile, unwavering glow of man-made light. The only misstep is the suffocating red lighting which accompanies the system-wide shutdowns occasionally forcing the house to reboot itself, a rather too obvious choice for a rather too obvious motif for the creator's inability to fully understand and control his creation. That said, Garland deploys the same lighting trick to enormously creepy effect during a dance scene set to Get Down Saturday Night, more effectively playing into Caleb's sense of being overwhelmed by his feelings of totally losing control of himself to Nathan's manipulations.

Despite Garland reaching the director's chair following a celebrated career as a novelist and screenwriter, his command of storytelling through visual language and the performances of his actors surprisingly proves more effective than his on-the-page plotting, which while commendably low-key and never losing sight of its subject matter, is a little predictable in its twists and occasionally blunt in its dialogue exchanges. There is never any doubt that Garland knows his audience is questioning everything shown and told to them, frequently doubling back on itself to maintain the same pervasive uncertainty which dogs Caleb throughout. Even with all the twists and turns, however, it's disappointing when more than once the obvious first guess turns out to be correct.

These are, however, minor quibbles in what proves something of a sister piece to Spike Jonze's Her. Where Jonze's movie played up the sadness of a time when many of humanity's most committed and honest relationships are to their machines and devices, Garland is more outwardly confrontational in condemning technology's role in reducing others, particularly women, to nothing more than an image on a screen to be observed, shared and manipulated at the user's whim. It makes a compelling case for the difference between attraction and objectification, with one a means of connection and the other a method of control. When Caleb asks Nathan why Ava was given sexuality at all, Nathan responds with what seems a considered response to humankind's compulsion to act and interact, before sneeringly pulling an about-turn by suggesting that what Caleb wants to know is whether or not he can fuck her, with the answer being yes. The worrying thing is that for all the philosophical grace of the first answer, one suspects that Nathan is correct in assuming the second is what Caleb really wanted to hear.

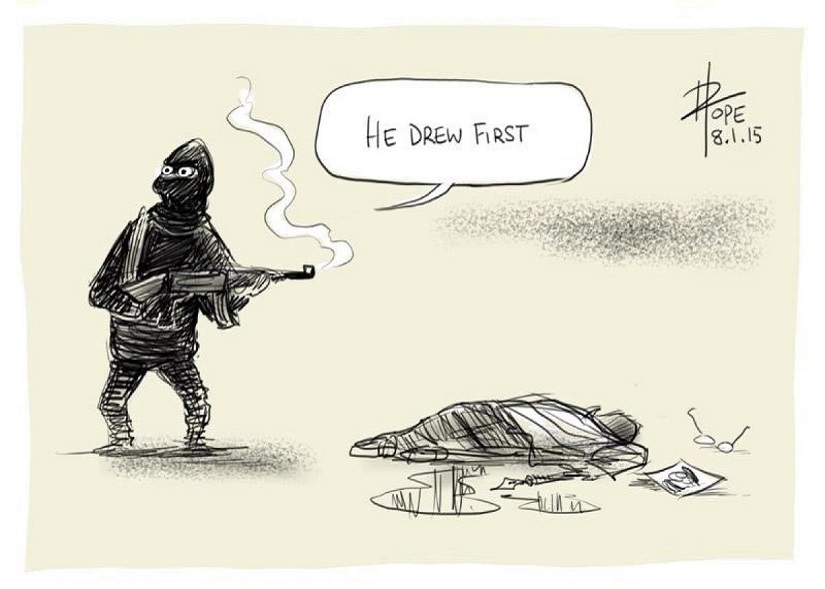

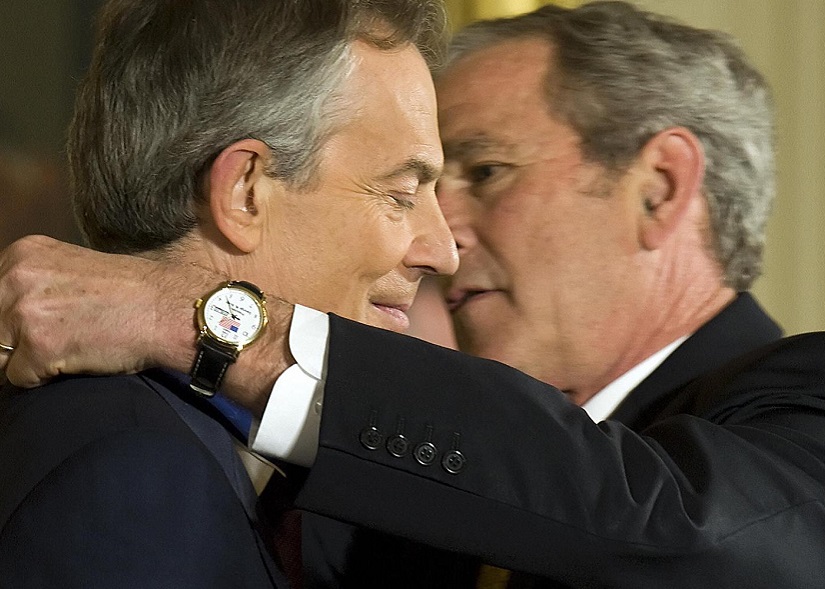

Is The Media Apologising For Terrorism In The Wake Of Charlie Hebdo?

It's been just over two weeks since the horrific attacks on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris, long enough for the initial surges of sadness and anger to die down and be replaced by something resembling more considered reflection. There's been considerable rumination on what the attacks mean for free speech and artistic expression, including by Ruby Hornet's own Hubert Vigilla, questions which eventually spawned a mini-debate of their own over whether Hebdo's representation of Muslims could be classed as racist. Elsewhere, many commentators haved raised the West's perceived responsibility in helping cultivate radicalisation as a result of mismanaged military incursions into the Middle East, notably the 2003 Iraq War.

More recently though, in addition to questions about why the Hebdo murders attracted so much more media attention than the slaughter of two thousand people by Boko Haram in Nigeria, another debate seems to have been gaining traction. This argues that, by the media so consistently using the attacks to raise questions about the West's actions elsewhere or to questions about the morality of the Hebdo covers at the root of the attacks, a process is taking place whereby the attackers themselves are having the responsibility for the murders lifted from their hands and transplanted into the laps of the culture and society which was attacked.

Despite being linked to recent events, the notion of the media being apologists for terrorist atrocities is not new. Its advocates have recently been linking to this blog post by (now deceased) political theorist Norman Geras, written in response to the London bombings in July 2005, a period when the Iraq War was still in its infancy and the world was still trying to make sense of the political and military landscape created in the aftermath of 9/11.

Geras argues that the pervasive culture in response to the bombings has been one of 'I told you so', where every mention of the tragedy of the bombings has to be suffixed with a reminder that it was our actions in the Middle East which must acknowledged as responsible for bringing these horrors to our doorstep. He goes on to mirror such reactions to the shaming of a rape victim rather than the rapist. In his words:

Bob, an occasional but serial rapist, is drawn to women dressed in some particular way. One morning Elaine dresses in that particular way and she crosses Bob's path in circumstances he judges not too risky. He rapes her. Elaine's mode of dress is part of the causal chain which leads to her rape. But she is not at all to blame for being raped.

The fact that something someone else does contributes causally to a crime or atrocity, doesn't show that they, as well as the direct agent(s), are morally responsible for that crime or atrocity, if what they have contributed causally is not itself wrong and doesn't serve to justify it. Furthemore, even when what someone else has contributed causally to the occurrence of the criminal or atrocious act is wrong, this won't necessarily show they bear any of the blame for it.

Others have argued that by using the terrorists' stated motives - blasphemy against the Prophet Muhamed - as a basis for condemning our own behaviour, we are perpetuating what this article by Yasmin Baruchi calls an 'us versus them' narrative, playing into the hands of extremist clerics using division as a tool of radicalisation. By debating whether Charlie Hebdo is racist against Muslims and accepting as a starting point that the cover in question was an act of blasphemy, Baruchi argues that rather than healing wounds, it has opened new ones by encouraging the perception that Muslims are mistreated, targeted and disrespected in Western society.

As author Jeremy Duns so succinctly tweeted on January 10th of this year:

Any fascist can murder cartoonists and simply say they were motivated by Abu Ghraib and somehow Bush and Blair share the blame. Brilliant.

There's a great deal in these arguments I disagree with. As was my response to Mr. Duns at the time, the danger of adopting these attitudes is that it risks encouraging the view that the West is nothing but a blameless victim, existing outside a cause-and-effect universe where events such as the occupation of a sovereign nation and power vacuum left behind can be given a free pass for possible consequences further down the line - even if those consequences involve our society subsequently becoming victims.

That, too, is where my issue with Mr. Geras' rape analogy arises. In this instance, the Charlie Hebdo attacks were undeniably a horrific attack on our culture and our society, yet Geras' metaphor (albeit for a different tragedy) neglects to take into account that such attacks are not isolated incidents but the latest in a long line, as tragic and shameful as the loss of life always is, but also inexorably linked to one another. Before these attacks, there were the myriad atrocities of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as drone warfare in Pakistan. Before that, there was 9/11. Before that, there was the first Gulf War, and so on. This chain goes back a very, very long way, leaving scars inflicted by both sides as far back as history records. A more appropriate metaphor might be gang warfare, where both sides alternate between being the victims and perpetrators of violence.

Geras, Baruchi and Duns are correct in calling out commentators who use these tragedies as a means of gaining backdoor support for their political views in much the same way that extremist clerics do to radicalise their followers. Just as there must be a time for self-reflection, it is equally important to honour the victims with a period of apolitical mourning, when we acknowledge the sadness of more needless death without turning it into propaganda. Considering the long and violent history of conflict between Western and Islamic cultures and ideologies, the media's readiness to lay the threat of terrorism solely at the door of the Iraq War is undeniably short-sighted: as Salman Rushdie would attest, Islamic extremism is hardly an invention of the 21st century.

I am, however, far from convinced that to make such a case involves morally absolving the Hebdo killers of the entirety of the blame for their crimes. Myopic and politically motivated, perhaps, but reflecting on how a murderer's background might have led to their crimes is not the same as letting them go free or diminishing their sentence. It is searching for clues as to what led an atrocity to occur and what it might be possible to do to stop it happening again. Perhaps, in the case of preventing terrorism, that means recognising mistakes we might have made in the past. Perhaps it means accepting that sometimes evil exists simply because it can, using outside circumstances as an excuse to justify itself. Humanity's need to find order in chaos can often be misguided or misappropriated, but if by hook or by crook it ends with one fewer instance of bloodshed on either side, I'd say it's worth persevering with.

[This Week In TV] Gotham, Archer, The Flash, Arrow

This Week in TV is a new weekly feature reviewing the best, worst and most interesting episodes of television from the past seven days. The plan is to cover a wide variety of shows, but not always the same ones each week, so let us know in the comments which ones you’d particularly like to read about. This week sees CW superhero staples Arrow and The Flash return after mid-season breaks, Gotham's mob war start to escalate and Archer... wait... goddamn it, I swear to god I had something for this.

Gotham - "What The Little Bird Told Him": Gotham is a show which has consistently struggled to find a coherent voice, too often allowing its most engaging elements to be drowned out by a lack of direction in their execution. The premise, taking in Commissioner Gordon's early days at the Gotham City Police Department prior to Batman turned up on the crimefighting scene, has plenty to potentially recommend it as a study of a city gradually sliding into chaos. Unfortunately, that potential has been, if not quite squandered, certainly restricted by a need to shoehorn every rogue from Batman's gallery into the series from the start - of the major players, only the Joker has been held back as a big reveal later down the line - while undermining attempts to create serious drama with an seemingly endless procession of ham-fisted winks to its audience.

The mob war storyline has consistently been the most engaging element because Robin Lord Taylor's Penguin is already effectively the character from the comics - albeit younger and slimmer - meaning the tedious in-jokes were abandoned after the first few episodes. Jada Pinkett-Smith's Fish Mooney is a new character, meaning the focus has been on establishing her character through actions rather than referencing. While Pinkett-Smith plays the part larger than life, Mooney is sly rather than spectacular, allowing her cold war with the straightlaced Dons Falcone and Marroni to build palpable tension and drama. Thanks to that comparative restraint, this episode's pay-off - wherein Fish's plan to induce Falcone's retirement and take over the family was ultimately foiled - succeeded thanks to the strong groundwork established through the steadily paced plotting and character development leading up to it. Sure, Penguin blurting out his allegiance to Falcone in a concussed stupour felt like a waste of a potentially strong dramatic pivot, but everything else, from the sympathetic nature of Fish's plan to Falcone's reactions, felt honest to the characters in a way the show too rarely takes the time to do.

The flip side of the coin (Harvey Dent reference, wink wink!) is Gordon getting himself back on the force by catching Jack Gruber, who escaped from Arkham under his supervision. The opening shot of Gruber, aka The Electrocutioner, walking the streets was a great way of anchoring an outlandish character in the real world, only for it to go to waste once Christopher Heyerdahl broke out his insufferable Hopkins-as-Lecter impersonation. Gruber's paper-thin motivation of killing Don Marroni came out of nowhere and allowed Gordon to take the credit for doing essentially nothing but throwing a glass of water at a fizzing box, played for a joke which never sparked into life (hey-yo!) because far too many of the series' villain-of-the-week plotlines have already had a tendency to fizzle out (OK, that's enough). Similarly, Morena Baccarrin's attractive doctor - if you can find any more depth to her character than that, I'd be glad to hear it - eventually got the kiss from Gordon she'd been chasing for whatever reason, and Barbara discovered her parents were just as sick of her as the audience is.

Archer - "The Archer Sanction": After last season's near-disastrous Archer Vice experiment, which stranded the characters in a plot arc that went nowhere and produced few to no laughs along the way, creator Adam Reed took the series back to basics with what was termed a 'de-boot' for its fifth year. Good thing too, because sometimes it's wise to be able to recognise when a successful formula is chugging along without the need for a shake-up, and last night's Archer made that point as effectively as any from the series' prime.

There was no danger of 'The Archer Sanction' springing a surprise of any sort, falling back on the safest of Archer episode structures - Archer, Lana and Ray go on a mission while Pam, Cheryl and Cyril create havoc in the office - and with a plot twist in the mission storyline which was obvious from the moment Crash McKerrin was introduced, despite an attempt at misleading the audience through the 'Axis power' hint. Incidentally, Archer's mistaking Ireland for an Axis power was an easier one to make than he was given credit for: the Irish sent condolences to Germany upon Hitler's death and the IRA were known to have shared intelligence with the Abwehr during the war itself. Given Archer's outstanding closing summary of Romania's involvement in WW2, perhaps he deserves a little more credit just this once.

Anyway, historical tidbits aside, the episode started magnificently with an inspired spin on the recurring voicemail gag, a well to which it returned a couple of times ("Sploosh!"; "You're not my supervisor!") to increasingly strong effect. Cheryl got the best obscure reference of the night, somehow oblivious to the inside of a watermelon being red despite knowing who watermelon breeder Charles Frederick Andrus was - something even Wikipedia can't claim. From Jessica Walter's exquisite delivery of "What fresh hell is this?" near the episode's end to the delightful visual gag of Archer snuggling up to Ray in a sleeping bag, 'The Archer Sanction' may not have offered much by way of twists, but was a welcome relief to see the show back doing what it knows and does best.

The Flash - "Revenge Of The Rogues": The Flash, like Gotham, has a bit of a consistency problem. When on form, there are few more outright entertaining shows on television right now. Its unapologetic joy in celebrating the tropes of the comic book superhero narrative are a blessed relief in the face of the urban grittiness and darkness which seems to have taken root in every other form of the genre, but it needs to start establishing some rules in terms of how far it is willing to stretch logic and narrative credibility whilst embracing that inherent silliness. Don't get me wrong, I understand that enjoying The Flash requires a certain suspension of disbelief in terms of, for instance, how fast Barry can actually move - that joke of him returning to his flat, clearing the place out and bringing his stuff back to the West household in less than a second, for instance - but there's a point at which an enjoyable stretching of the rules breaks into outright stupidity, which is where the climactic showdown in 'Revenge Of The Rogues' unfortunately ended up.

It's a shame, because everything until then was plenty entertaining. Wentworth Miller and Dominic Purcell's performances took the material by the scruff of the neck, with both clearly having a great time in bouncing Miller's calm and calculating Captain Cold off against Purcell's never-not-livid Heat Wave. Is it wrong that I was hoping that Miller would get the chance to throw out at least a couple of ice puns? Probably, but Purcell's furious delivery of his "I'm the heat!" line just about made up for it. On the side of the angels, Grant Gustin continues to give one of the most charming performances going, even if he's better suited to his character's moments of glee than angst. The latter is not an emotion which suits this show well - and yes, I do know it's on the CW - which explains why Candice Patton's Iris so often finds herself trapped in the show's most tedious material. Her purpose remains unclear outside whomever she's having a relationship with and having her turn up in a panic at a superhero showdown for no good reason further undermines efforts to portray her as intelligent and independent.

That showdown was problematic for much bigger reasons though, first among which was the fact that no explanation was given as to why Barry couldn't simply have used his speed to disarm both Cold and Heat Wave in a fraction of a second; why he couldn't have knocked them out before they'd finished their first sentence (although the "Scarlet Speedster" nod will have warmed the hearts of many a comic fan); why the police couldn't have simply shot or tazed them from afar - as stated in-ep, they aren't bullet-resistant metahumans - and what the point of establishing a cordon was if they weren't going to actually do anything. There are leaps in logic that are forgiveably fun ("Absolute hot") and those which just make everyone involved look foolish, which became an increasingly prominent issue as the episode went on. Barry and Joe's adorable chill-out session at the close brought everything back to the series' biggest strengths, but Flash will have to keep an eye on exactly how far it wants its comic book logic to stretch if it wants to keep its villains as engaging as its heroes.

Arrow - "Left Behind": Despite being the star of the show, it never hit home for me quite how much Arrow centred around Stephen Amell's Oliver Queen until 'Left Behind' took him out of the picture. Roy and Diggle fill in on the crime fighting front, but without our Ollie there to provide a centre of gravity for the other characters to orbit around, the episode's main plotline felt weightless and discordant despite providing much of the usual Arrow fare. Amell's tortured seriousness can be awfully one-note at times, but as the old saying goes, you only know how much you miss something when it's gone. Whether intentionally or not in an episode very much about ramming home the absence of the Arrow crew's presumed dead leader, 'Left Behind' struggled to find anyone among the series' extensive supporting cast to fill that Ollie-shaped hole (phrasing).

Part of the reason might be because, for all the cast's talent, Ollie has been the one hogging all the character work for some time now. Diggle's admission that he still thinks of himself as a bodyguard was an accidental reminder of how little he's shifted from that original remit, while Roy's early potential as a street-savy superhero has gone completely neglected in his transformation into Arrow-lite. Even Felicity, beloved Felicity, has been reduced to an Iris-esque state of being defined by her sex life rather than her abilities. Her fear of losing more friends never quite rung true beyond despair at the death of her unrequited love interest and as entertaining as Brandon Routh is as Ray Palmer, his character is not yet well enough developed for him to be an effective emotional foil.

It was left to the villains to carry the piece, which is fortunately never going to be a problem Vinnie Jones and John Barrowman are at hand. Brick would seem to be the series' first villain with a non-Mirakuru supernatural ability, an interesting turn somewhat lost amid the moping elsewhere even as Jones played the part to its cockney hilt. Barrowman never stops being good value as Malcolm Merlyn and his habit of turning up unannounced in the Arrow cave made for the episode's two strongest scenes. The Hong Kong flashbacks felt somewhat rote, required more to remind us of certain characters before the final reveal and to inject a by-the-book action sequence into proceedings, so hopefully it won't be long before Oliver Queen returns to Starling City to take his rightful place back at the centre of the Arrow universe.