So What's The Best J. Cole Album So Far?

The J. Cole hype couldn't be greater right now after the 4th major album release from J. Cole, For Your Eyez Only. Many are expecting it to be album of the year with only 2 songs released. They are also expecting it to be "another classic" [See Social Media] and it made us think. What is the best J. Cole album so far?

3 - Cole World: Sideline Story. Sideline Story is the hands down laziest album for me. When I heard Cole say he added songs from his mixtape to this album because he felt enough people didn't hear them, I immediately lost my interest in buying it. Emcee's shouldn't do that. Sorry. I toss this one to the bottom of Cole releases because I heard a lot of it before the wave got real.

It's interesting going back and listening to this album now. It's difficult to replicate the hunger you hear in the very young J. Cole's voice in nearly each song. This is often the case with many rappers when juxtaposing their early catalog over their more recent works. The effect this has is ultimately subjective, but for us it's clear young Simba was not yet the king.

[iframe id="https://www.youtube.com/embed/ZOrPNbKHQm8"]

2 - 2014 Forest Hills Drive. The Platinum with no features album. The album that inspired a bunch of jaded, misguided and misspelled memes for the last 2 years. It's not that this album is whack necessarily, it just doesn't move me. The middle of this album made me dose off. I'm not a fan of the singing efforts. Tracks like "St. Tropez" and "Hello" come of as somewhat forced and, as a result, slightly in-genuine.

What's more, tracks that were clearly intended to be in more of a pure hip hop vein, like "Fire Squad" turned out to be little more than filler. To be clear, Cole had hits on this project. "Wet Dreamz" and "Tale of 2 Citiez" are both catchy and have a well-rounded appeal. "January 28th" and "No Role Modelz" are anthems in their own right as well. To us, they were just too few and far between to justify ranking this album higher up. To the Cole Stans, we're sorry, but 2014 a little boring. We credit cole for giving us a bunch of new music though.

[iframe id="https://www.youtube.com/embed/ijy2GFWqeAs"]

1 - Born Sinner: This album was a hype beast dream. New Rappers, good features, Hit singles and was deemed a classic because everyone hated Yeezus and didn't pay attention to The Gifted by Wale. This album is the best of the 3 to me because it's the best representation of what Cole can do. Songs like "Land of the Snakes" serve as a verbal exhibition for Cole, with a concise, driven flow over an equally driven instrumental.

"Trouble" was a favorite off of the album, featuring a menacing instrumental with Cole's cocky humor at play on top of it. Born Sinner made it clear that he can make hits if he wants. He can really rap. He has the potential to be a great producer. The subject matter isn't that great or diverse, but I honestly feel the release of 2014 FHD builds the appreciation of Born Sinner. It's number 1 for me, but not cause it is "so much better" than the other releases around it.

[iframe id="https://www.youtube.com/embed/UCjl3xEdA_k"]

Check out more on Cole here.

Horror Movies: How Have They Changed?

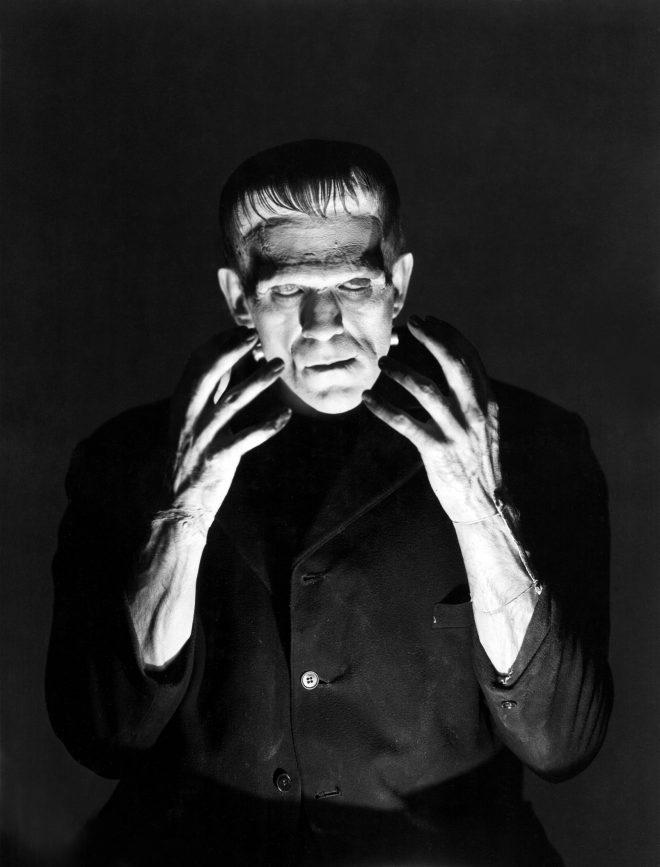

Since the early 1930s, after the release of the first talkies movie, monster movies became a major hit. Films like Dracula and Frankenstein set the president for horror films during this period.

Here’s a look back at a few of the original "monster” movies and how these supernatural creatures were portrayed during the 1930s/1940s in film:

- Dracula (1931) —> The film begins with local residents speaking about the legend of Count Dracula as a vampire, creatures that feeds on the blood of humans. Renfield, who plays a logical minded non-believer at the beginning states that it is a matter of business. Renfield says that he must go up to visit Count Dracula. The representation of vampires in Dracula is shown through the coffin in a dark, dirty basement with bugs and rodents. This image is not as glamorous as how vamps are portrayed in today’s movies and television. However, there are elements of vampire myths with strong ties to how they are viewed in television and movies today. Even the smallest amount of blood draws in a Vampire, which is still true in Vampire film and shows today. In Dracula, even the sight of a cross repels vampires. This mythical ideal has also been used in on-screen content such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Dracula’s appearance doesn’t appear in the mirror, which goes along with myth that vampires can’t show a reflection in mirrors.

- However, there are other elements, both mythical concepts of vampires as well as on-screen presentation and formatting, that has changed over the years. For example, the light that hits around Dracula's eyes, magnifies his eyes and leaves the rest of his face in shadows. Dracula’s lit up eyes seemingly draw in his victims, while mildly paralyzing them enough so that he can feed on them without a fight. This image of glowing eyes in vampires hasn’t changed completely, but has been altered in correlation with technological advancements. Dracula is able to enter into Lucy Westenra's room without an invitation inside, which goes against the famous myth that vampires need to be asked inside a person’s home; a concept that is often employed in vampire themed movies and television today. Renfield belongs to to his “Master,” Count Dracula. Renfield’s persona is different. It appears he has gone “crazy.” His new behavior is also shown in a newspaper story that states that was “a raving maniac; his craving to devour ants, flies, and other small living things to obtain their blood puzzles scientists. At present he is under observation in Doctor Seward’s Sanitarium near London.”

- Professor Van Helsing believes that Lucy death was the result of a vampire; but his associate Dr. Seward argues “Modern science does not admit to such a creature.” This theme of believe vs. non-believe and sane vs. insane appeared to be a very structured way of introducing the supernatural; we also see this concept in movies such as Frankenstein and Wolf Man.

- Frankenstein (1931) —> The film begins with the famous opening presentation of Frankenstein that warns the audience what they are about to see may “horrify you, and may even shock you”; a presentation that is often reused even today when introducing a Frankenstein-themed story line. The story opens up with Henry Frankenstein, a scientists who is creating new unusual experiments and attempting to creating life through science by his “own hands.” When those closest to Henry discover his disturbing experiments, Victor calls Henry crazy at the idea that Henry thinks he could create such a monster. Henry truly believes that his experiment will work, stating, “A minute ago you said I was crazy. But tomorrow, we’ll see about that." But it is important to note that even if Henry's invention works, doesn’t make him any less crazy. Maybe he is crazy for simply conjuring up the idea to create this inhuman creature in the first place, whether it works or not.

- Once Henry’s creation comes to life, he screams, “It’s alive! Now I know what it feels like to be God.” Henry doesn’t see the flaws in his creation plan or that it could be potentially dangerous, and that no human being has the power to play God. Henry refuses that it could be dangerous when Dr. Waldman addresses this issue with Henry. Henry seems to believe that dangerous and adventurous are synonymous. “You have created a monster and it will destroy you,” said the doctor. “Patience, I believe in this monster, as you call it,” Henry responds. After Henry experiences his creation's behaviors, he starts to realize that he created a monster. Henry and Dr. Waldman then attempt to try to kill the creature.

- The audience can see these “shocking” actions from the creature of Frankenstein coming. There is a visible lead up to Frankenstein’s attacks on Dr. Waldman and Elizabeth create a sense of build up and even intensity, to some extent, for audience members. Yet the build up and intensity differs from movies and tv shows today. On-screen horror content today is created by using pop-outs and sudden actions shock audiences. Every scene is pre-meditated, from the slow creation of Frankenstein to the crowd of people with lit torches chasing down Frankenstein. It is believed that Frankenstein, the creature, is finally dead and the town rejoices. However, the film Frankenstein’s Bride reveals that Frankenstein is still alive. This method of shocking the audience by bringing about a part 2 to the story is an example of when films and television first began; a method that still exists today.

- The Wolf Man (1941) —> The film opens up by providing a definition at the beginning; a method that rarely, if ever, that still lives on in films and television today. Lycanthropy (werewolfism) - a disease of the mind in which human beings imagine they are wolf-men. Larry Talbot, who is the lead role, portrays a kind gentleman with clear moral boundaries and standards. Yet, his morality is put into question after killing the fortune teller, who was a were-wolf. Although Larry thought he simply killed a wolf, the appearance of a dead man challenged everything he thought that he knew. Were-wolf myths in the film aren’t as common as in today’s on-screen were-wolf lore. For example, “A were-wolf is a human being who at certain times of the year turns into a wolf,” says Gwen Conliffe. “Every were-wolf is market with a pentagram, it sees it in the palm of his next victims hand,” she continues.

- Although there are no surprises, with completely expected scenes, audiences during the 1940s may have had different perceptions of shocking and unexpected occurrences in films. Maybe it is the telling of the lead character’s story, rather than unexpected plot twists, that entertained audiences during the 1930s and 1940s.

- Larry’s first kill as a were-wolf shows hesitation, briefly addressing his inner humanity and the morality of his human side. Yet, the animalistic primal urges lead Larry to ultimately kill. Larry is hated by the towns people as an animalistic murder for killing the psychic who he seemingly thought was a wolf. The doctor views Larry as sick when Larry asks the doctor if were-wolves exist; because he is mentally sick, the Dr. states that he should leave town as a result of his “sickness”; Sir John Talbot ties up his son, Larry. Sir John tells the doctor that Larry will realize this is all in his head after the hunt is over. However, the gypsie women’s words force Sir John to confront his thoughts/suspicions all along that maybe Larry really is a were-wolf. When the were-wolf Larry attacks Sir John, Sir John has no choice but to kill the animal, his son.

- As in movies such as Dracula and Frankenstein, Wolf Man presents a similar theme of these supernatural creatures in which you need to see to believe. However, seeing these creatures also brings these characters to question their own sanity.

- The Wizard of Oz (1939) —> This film differs from the typical image of scary movies involving a supernatural creature/s during the 1930s/1940s period; Yet, the Wizard of Oz was the first popular portrayal of witches in movies. The film doesn’t confine the image of witches as simply evil or wicked. The Wizard of Oz shows the good and beautiful witch, Glinda, who helps Dorothy; versus the Wicked Witch of the West, who sets out for destruction and the powerful Ruby slippers that Dorothy; possesses. This interesting plot line that brings an array of unique, un-human creatures into one story line. Most of the un-human creatures, such as the lion, the scarecrow and the tin man are all morally good; they all have good intentions, despite their self perceived flaws of lacking a heart, a brain, or courage. Movies and tv shows on the subject of witches didn’t become popular until the after the 1960s. The topic on witches expanded largely in the mid 1980s and into the 1990s with films like The Witches of Eastwick, Hocus Pocus, Practical Magic, The Blair Witch Project, etc.

In nearly 100 years, the portrayal of on-screen monster films and television has changed a lot. Movies and television have evolved a lot over a century. But one of its most prevalent examples is in the supernatural/horror genre. Today, horror movies have more intense scenes, more complex and heavily involved story lines, and technology that has majorly enhanced the appearance of these mythical supernatural creatures. Even the depiction of these monsters and their character arcs have become more involved over time. New or old, it is interesting to see the evolution of these legendary on-screen creatures. And of course the original on-screen depiction of the monsters that started it all.

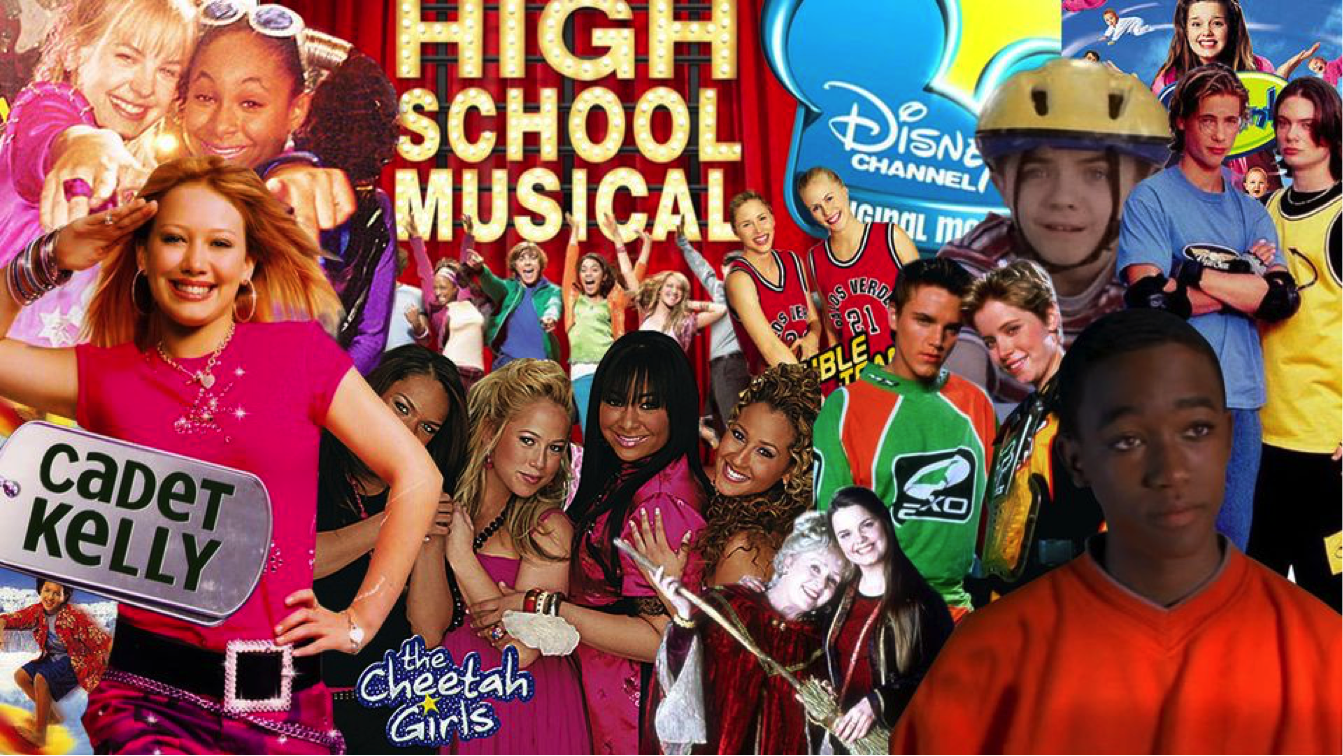

Disney Channel Original Movies: Have They Changed?

Being a kid in the 90s and watching disney channel at least 50% of the time, I also grew up loving disney channel original movies. So obviously, I started to binge watch as many dcoms as I could when I noticed they were on demand. Here’s a list of the top 6 Disney Channel Original Movies worth mentioning:

- Zenon (1999) (6.4 rating) —> A young girl takes on the task of saving her home and community in outer space with the help of her friends and family.

- The Color of Friendship (2000) (7.4 rating) —> This dcom discusses the impacts of environment, race and culture on relationships and how a child's sense of morality and friendship is not confined by where you come from or the color of your skin.

- Motocrossed (2001) (6.8 rating) —> This movie focuses on female strength and that a girl/woman can succeeding in anything they put their minds to, especially with the strength and support of friends and family.

- Tru Confessions (2002) (7.8 rating) —> This dcom highlights something much more important than a child with disabilities. Tru Confessions shows what the support of family really means and that disabilities don’t define you. To Tru and her parents, her brother Eddie is a brother, a son, and a friend first and foremost.

- Jumping Ship (2001) (6.3 rating) —> This movie shows how three individuals, despite their differences, can work together to survive and create strong friendships with one another. Although this movie contains a lower rating, this was my favorite dcom growing up as a kid.

- Double Teamed (2002) (6.2 rating)—> This movie shows the value of teamwork and sisterhood, and sportsmanship. It also highlights that everyone is an individual and everyone is different, even twins.

Imagine, for those who grew up with these movies, watching disney channel original movies for the first time as adults. Our admiration and loyalty for some of these disney films probably wouldn’t be as strong.

As a kid, these movies were pure entertainment. But the life lessons buried within these movies also helped to inform us. It provided us kids with strong examples of morality in family and friendship.

This brings into question whether disney channel original movies were better 20 years ago compared to today, which seem cheap or cheesy to me now. Somehow, dcoms today seem to pale in comparison; that they are not the same level of quality as dcoms of the late 90s/early 2000s. However, could this just be because as adults, we view these kids movies differently now; rather than our innocent, undeveloped child brain would.

According to IMDB the majority of dcoms, both new and old, contain ratings ranging between a 5.5 and a 7.5; this would be deemed on the lower side of average. But again, this system of rating by adults goes back to the same concept. Watching these movies as adults takes on a completely different perspective of Disney Channel Original Movies compared to the child adoration of these movies. Watching dcoms at a young age impacts both the kid watching these films; as well as a nostalgic adult remembering the young fondness for Disney Channel Original Movies.

Series Recap - Mission: Impossible - Ghost Protocol (2011)

After Mission: Impossible 3's straight-faced, character-driven approach made a messy attempt at returning the series to the first movie's cereberal roots, Ghost Protocol seems a natural companion piece to Mission: Impossible II. For one thing, Ethan's hair has grown long again, while the movie adopts the same all bombast, all the time style which John Woo made so intolerable through endless empty flourishes and Robert Towne's lousy screenplay. If M:I3 was a lesser imitiation of the original, though, Ghost Protocol director Brad Bird takes the philosophy of M:I II and makes the movie that movie should have been. There's no nonsense about Scottish doppelgangers, disquisitions about heroes and villains or ridiculous showboating here. Instead, the fourth entry in the series has nothing more on its mind than delivering two hours of relentless entertainment. It succeeds admirably.

Perhaps the most telling difference between this and M:I II is that where Woo's movie came across as an extended Tom Cruise ego trip, Ghost Protocol delights in how much physical damage it can inflict on its star. Bird turns Hunt into Wile E. Coyote, a figure whose absence of personality matters not in the slightest when the real pleasure is watching him get pulverised on a semi-regular basis. This in turn makes him quite a bit more likeable than the two previous movies, if only because his sheer persistence in the face of constant physical trauma becomes amusingly, morbidly admirable. Rarely has even the boldest action movie climax been so unashamedly Looney Tunes-esque as the ridiculous showdown in a high-tech car park, culminating in Hunt driving a car down a straight drop of several floors to the concrete ground.

The plot is so thin as to barely exist. The IMF team is framed and disavowed following the destruction of the Kremlin, for which responsibility lies with Kurt Hendricks, a man determined to start a nuclear war for reasons no-one can entirely fathom. Hendricks barely appears at all, to the extent I'd mostly forgotten there even was a main villain for most of the movie's running time. Bird uses plot as little more than a loose framework around which to build a set-piece delivery machine, churning out one action sequence after another with little interest in developing the narrative in any meaningful way. Where that might be problematic in lesser hands, Bird shoots each sequence with such freewheeling energy that it's a joy just to be taken along for the ride. Making his live action directorial debut off the back of Pixar's The Incredibles and Ratatouille, there's a clear cartoonish influence on the way he gleefully abandons reality in search of squeezing every drop of entertainment and comedy value out of each frame.

The Burj Khalifa sequence, the apex of the series' love of vertical action, is the most thrilling of the lot and among the most astounding movie set-pieces of the decade so far. Benefiting enormously from Cruise's devotion to performing every stunt himself, Bird delights in evoking the vertiginous heights Hunt is manoeuvering above. Having Hunt climb the side of the world's tallest building isn't enough, of course, so the movie throws in a number of terrific visual gags surrounding his malfunctioning adhesive gloves and a variant on the fulcrum technique used for a skyscraper break-in in the last movie, here employed in an insane attempt at returning to the hotel room from whence he came and naturally faceplanting a window on the way. Anyone who missed seeing it in IMAX should be kicking themselves, but it is shot so well as to work almost as effectively on the small screen. After the overblown blue-and-oranges of M:I3, Robert Elswit's cinematography puts a strong emphasis on bringing out the colour and vibrancy of each location. Ghost Protocol is frequently gorgeous to look at and captures the distinctive identity of each destination in a way Woo and Abrams so comprehensively failed at.

What anchors the movie is the strongest team dynamic of the series to date. Simon Pegg returns from M:I3 and is given far greater prominence as the movie's comic relief gadget maestro. With Ving Rhames' stalwart Luther held back until a cameo at the end, Jeremy Renner and Paula Patton are the newcomers making up the rest of the team. Renner is wonderful as Brandt, a grumpier, more reluctant version of the Ethan Hunt from the first movie and something approaching a voice of sanity in a world gone utterly bananas. His chemistry with Pegg and Cruise is immediately endearing, even if his links to Hunt's past feel a little shoehorned in. Paula Patton's Jane Carter gets a slither of backstory, immediately making her the series' best developed female character. While Patton isn't an especially strong actress, she looks believeable tough - her kicking off her heels before going into battle is a small, badass wonder - and rocks a cocktail dress to brain-melting levels of hotness.

The movie's approach to continuity is interesting, although not altogether successful. The reveal that Brandt was on the security detail assigned to protect Hunt's wife, Julie, when she was ostensibly killed just sort of sits there, serving little purpose until a faintly sweet coda in the final scene. The question of what actually happened to her is brought up a number of times and drags the pace down each time. I appreciate the movie not simply ignoring its predecessor's potentially difficult resolution, but a shorter, sharper explanation would have been more than sufficient. A callback to the manner in which Hunt is taken to see Max in the first movie is a fun if nonsensical nod, but can't help but feel disappointing when the imperious Vanessa Redgrave fails to turn up. That Hunt instead turns out to be making a call to the man he freed from a Russian prison (to the tune of 'Ain't That A Kick In The Head', no less) in the first act pays off that foreshadowing reasonably well, but if you're going to tease one of the series' most vivid characters, you'd damn well better deliver. Much better is how the movie's final line is used to slyly set up the events of Rogue Nation, which will have a hell of a job on its hands if it's to raise the bar on Ghost Protocol's stupendous action extravaganza.

Series Recap - Mission: Impossible 3 (2006)

Following the widely-derided Mission: Impossible 2, the series remained dormant for a full six years before JJ Abrams, then best known for his work on TV spy series Alias, was brought onboard to try and resurrect it. Star Tom Cruise was also in need of a vehicle to win back his place in the heart of moviegoers, having undergone a series of PR disasters after unceremoniously firing his agent in 2004. Despite still being a draw at the box-office, with such successes as Minority Report, The Last Samurai and War Of The Worlds under his belt, his star's public persona was seen as increasingly alienating, with his close support of Scientology becoming ever more pronounced.

There's a clear sense in Mission: Impossible 3 of drawing back from the garish excesses of the second movie to something more intimate and character-driven. Having recently married Katie Holmes and with a child on the way, one suspects that public cynicism regarding the authenticity of Cruise's family life may have played some part in the direction that M:I3 was taken. That may give you some clue as to how well it turned out.

Anyone familiar with Alias will immediately recognise why Abrams was brought onto the movie. The plot bears a number of resemblances to motifs employed repeatedly throughout the series, most notably opening in media res and featuring a protagonist struggling to keep his professional life as a spy separate from his personal life. Following his escapades spanking Dougray Scott around in Australia, Ethan Hunt is, in fact, no longer an active field agent but an instructor. His protégé, Lindsey Farris (Keri Russell, playing against type), is kidnapped while investigating an arms dealer, Owen Davian, who is trying to get his hands on a mysterious weapon known as the Rabbit's Foot. Hunt has also found himself something approaching a steady home life, though his fiancée, Julie (Michelle Monaghan), is entirely unaware that his real job is considerably less mundane than the post she believes he's holding down at the Department of Transportation.

If that's seems like a lot of backstory to get through before the plot even begins, you'd be right. The movie starts with the series' most powerful cold open, in which Davian holds a gun to Julie's head and threatens to kill her if Hunt doesn't tell him the location of the Rabbit's Foot by the time he's finished counting down from ten. This short sequence packs in a huge amount of information without betraying the intensity of the scene. While gripped by the sight of the normally cool-headed Hunt descend into pleading desperation as each of his negotiating tactics fail miserably, we're subconsciously absorbing small details (Hunt having someone extremely close to him under threat, the value of the Rabbit's Foot, Hoffman as the villain, etc) to be expanded upon later.

Unfortunately the effortless power of that opening scene doesn't expand to the rest of the film. The plot is heavily streamlined in order to keep things moving, which wouldn't be so bad were so much essential information not left missing or underdeveloped. We have no idea how Hunt and Julia met or why they're attracted to each other beyond physical appearance, or even who they really are as people. Knowing so little about the two characters makes investing in their relationship a real mission: impossible (badum tish) as neither is given the slightest bit of depth either individually or as a couple. Monaghan's natural sweetness almost pulls it off on her end, but Cruise has never seemed more robotic or unnatural. The scene in which Hunt throws a party to meet Julie's family shows him descending into outright creepiness, as he starts reading people's lips and injecting himself into their conversations. As mentioned previously, playing romance has never been Cruise's strong point and the straight-faced nature of his scenes with Monaghan make the uncanny valley of his performance as Likeable Human Male all the more pronounced.

The spy stuff is more interesting by default, but still feels strangely hollow. The heavy use of colour grading in any scene set in an urban or industrial environment overemphasizes the blues and oranges to such an extent that the movie often has the look of a particularly offputting DVD cover. Abrams' direction is acceptable, but while it's a relief not to endure any more of Woo's tiresome flourishes, his inexperience on film is painfully obvious. He shoots with the technical precision required on television, but fails to establish any sense of grandeur. The entire movie feels like a (remarkably expensive) feature-length series finale, only becoming truly cinematic in the terrific sequence in which Hunt's convoy, carrying the captive Damian, is assaulted by air while crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. The narrative streamlining also makes it difficult to invest in the plot, as keeping the nature of the Rabbit's Foot secret means there's no sense of the scale of the threat in question. Simon Pegg's Benji postulates a theory about it being the anti-God, but the suggestion is so over-the-top, and immediately dismissed by the character himself, as to be nothing more than empty hyperbole. The intention is obviously to keep the focus on the personal stakes for Hunt after Julie is kidnapped, an admirable goal which flounders due to that relationship being similarly underwritten.

What does work is Philip Seymour Hoffman's performance as Davian. Rather than going full-on with boorish villain theatrics, Hoffman takes an unexpected road by imbuing Davian with a chilling, sociopathic stillness. He may not be the most physically dangerous antagonist Hunt has faced, but he's aware that the morality restricting the actions of Hunt's team makes him effectively invincible. His calmness is a sinister reflection of his absolute confidence and amorality, making him a grippingly atypical foe for the genre. Also fun is the set-piece in which Hunt breaks into the Vatican, which features a number of strong visual gags (and a mesmerising effect in which Hunt's Hoffman mask seemlessly transforms him into Hoffman) and an interesting location missing from the factory/skyscraper infiltrations which make up two of the movie's other major set-pieces. It's just a shame Hunt's team suffers the depth deficiency which diminishes all the movie's major characters, though there's at least a genuine sense of friendship between Hunt and his three-time partner Luther (Ving Rhames), while Maggie Q is just natural enough in her performance as Zhen Li not to disappear as thoroughly as Jonathan Rhys Meyers' Declan, who is notably solely for his terrible Irish accent.

The movie rediscovers its verve a little for the Shanghai-based climax, but even then struggles to elevate itself to heights above forgettable adequacy. True, that's a huge step-up from M:I II, but hardly the sort of recommendation needed to revive a series struggling for relevancy in the wake of the hugely successful Jason Bourne movies and Daniel Craig's soon-to-be-lauded debut as James Bond in Casino Royale. Fortunately, the fourth entry in the series, Ghost Protocol, would find in Brad Bird a director capable of marshalling the series' disparate tones into something more enjoyable and distinctly its own. Check back tomorrow for the final entry in our series recap.

Series Recap - Mission: Impossible 2 (2000)

While Brian De Palma's Mission: Impossible was a financial and criticial success, questions about its hard-to-follow plot were seemingly taken to heart when producers Tom Cruise and Paula Wagner sought to redirect the sequel away from the original's atmospheric blend of summer blockbuster and old-school action thriller and into more unashamedly spectacular action territory. The hot action director at the time was John Woo, coming off the back off a number of successful American ventures after establishing his name with the likes of The Killer and Hard Target in his native Hong Kong.

The kindest thing that can be said about Mission: Impossible 2 is that it's sort of interesting for being a movie which bears virtually no resemblance at all, in plot, characters, tone or visuals, to its predecessor. Cruise's character may be once again called Ethan Hunt, but to all intents and purposes, the protagonists of the two films manage to be completely different men despite both being largely blank slates in terms of personality. Woo's melodramatic style, matching heightened action with ludicrously hammy symbolism and near-abusive quantities of slow motion, certainly has its lurid charms when expressed in full, self-mocking regalia - see the wonderfully barmy Face/Off - but is made instantly insufferable by being used as a misguided tool to enhance the cool factor of its star.

Every frame of Mission: Impossible 2 reeks of pandering to megastar Cruise's ego. Woo's camera is never shy of zooming in at just the right time to remind the audience of the actor's toughness, rebelliousness, sensitivity, or just for one more look at that sexy, sexy Tomface. Having been more intellectual than fighter in the previous movie, Hunt grew his hair into an Aaron Carter mop in the interim and realised thinking was for dorks. After all, why strain the ol' brain when the possibility exists to instead thump someone in the face with a flying kick, or engage in a little motorbike foreplay with the Scottish doppelganger with whom you share a girlfriend? To describe the movie as substance-free is an insult to things which don't exist. It's so monumentally vapid and self-involved that it makes existing things want to disappear until it's all over.

The small moments of irony which do sneak through are among the movie's most enjoyable, although that's not saying much. It could be suggested that Woo was trying parody a certain kind of overwrought, star-driver blockbuster, but even if true, the few moments in which the satire registers are greatly outweighed by its extensive pandering to that same formula. Villain Sean Ambrose, played with all the toughness of a wet flannel by Dougray Scott, is supposed to be the anti-Ethan, but Ethan himself is such a non-entity that Ambrose himself just comes across as a preening, petulant pronk. His two moments of success both come in mocking Ethan, once describing how the hardest part of imitating him - more on that in a moment - was having to "grin incessantly for fifteen minutes" (more a jab at Cruise than Hunt) and later in contrasting his own 'kill first, think later' approach with Hunt's eagerness to perform "some aerobatic insanity before [risking] a single hair on a guard's head". It's worth noting that this is the first movie in which Hunt is shown performing anything like aerobatics, and while he was undeniably something of a pacifist in the first movie, here his approach is every bit as driven by guns and fists (steady) as Ambrose.

Leaving aside Scott's flaccid performance, what little sense of danger Ambrose might have possessed is dissipated the moment he's shown to be so blindly lovestruck by his ex-girlfriend, Nyah, that he willingly invites her into his lair despite it being such an obvious trap that he himself notes the contrivance of the whole scenario. The risk doesn't matter, he explains to his bodyguard, Stamp (played by Richard Roxburgh), because he knows she's a snitch and will get rid once he's bored of having sex with her. If that doesn't sound like an altogether honourable way of handling a female character, it's as good as it gets for poor Thandie Newton. The first scene positions Nyah as a master thief, only for those skills (bar one instance of straightforward pickpocketing) to be consciously discarded in favour of making her the rope in a tug of war between hero and villain over who gets to have sex with her. Like many 'strong female characters', she does all the sassy posturing supposedly proving her an equal to the menfolk - although if that were true, she wouldn't be required to prove it - only for the narrative to reduce her to a brainless plaything for Scott and Cruise, whose career-long inability to convincingly play romance is emphasized to a painful degree here with such clunking lines as "My God, you're beautiful". I do like her name though - Srta Nyah Nordoff-Hall - so that's something.

Let's also talk about the face masks, a fun little gimmick in the first movie but used incessantly here. The plot starts off with Ambrose 'doubling', needlessly, for Hunt, then continues in that vein throughout, with everyone seemingly having a mask of everyone else just in case it happens to come in handy. Yes, it's supposed to emphasize Ambrose and Hunt being the same person on opposite ends of the moral compass - much like the pathogen and antidote making up the movie's Macguffin and described by Dr. Nekhorvich, their Einstein-y creator, as villain and hero - but such symbolism doesn't follow through when you have Hunt imitating Nekhorvich and Stamp as well. What's that supposed to symbolise? Instead it functions as lazy shorthand to engineer some decidedly unshocking twists into a plot which could not be more rote if it tried: Ambrose wants to loose the Chimera virus on Sydney to increase the value of the shares he owns in the company manufacturing the antidote.

Sydney also makes a resoundingly dull location, having so little identity on-screen that the best settings the movie can muster up are a racetrack, a skyscraper and a bunker, with a remote sheep farm thrown in for good measure. The city dominates the movie's running time, but there's so little sign of any local history, unique architecture or culture that a very brief excursion through Seville offers infinitely more flavour in a tiny fraction of the time. It's a hollow location for a thoroughly hollow movie, a stark contrast in every way to its complex, compelling predecessor. Action movies don't need to be intelligent or even make a great deal of sense, but do need to offer something more than an excuse for the star to posture and prance about the place trying to remind everyone of what a badass he thinks he is, even when the embarrassing transparency of the act is immediately apparent to everyone forced to endure it.

It's no surprise M:I II (yes, that's the official abbreviation) marked the start of a downturn in Cruise's career, to the extent that when the series' second sequel was released a full six years later, his deteriorating public image was seen to have a negative impact on the movie's marketing. Check back here for my coverage of that movie tomorrow.

Series Recap - Mission: Impossible (1996)

Ahead of the release of Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation this Friday, I'm going to be looking back at the four previous installments in the series to chart the evolution from one film to the next and see how well they individually hold up. The M:I movies are especially interesting in this regard because where most action blockbuster franchises settle into a bland uniformity once the sequels start churning out, each entry in this series is most notable for how different they all are from each other. Even the Bond series, which over its fifty-odd year history has reinvented itself time and time again, does not come close to the tonal disparity existing between each new M:I release.

The original, directed by Brian De Palma, remains my favourite and the most tonally distinct of the four to date. Where John Woo's sequel, which I'll cover tomorrow, turned the series' focus almost exclusively to big-budget action, De Palma's Mission: Impossible is more interested in plot and atmosphere than large-scale shootouts or big action set-pieces. True, the climax in the Channel Tunnel is as enjoyably loopy as anything which would follow, but the film leading up to it channels the intricately plotted Cold War spy thrillers of the '70s rather than the typical blockbuster fare of the time.

The plot starts off with a mission to retrieve a leaked list of undercover agents going horribly wrong, leaving Ethan Hunt the only surviving member of his team. Under suspicion of being a traitor, Hunt sets about following leads to uncover the person who really betrayed him. At the time, the movie was mockingly referred to as Mission: Impenetrable for its convoluted storytelling, possibly one of the reasons why subsequent entries in the series have kept plotting to a bare minimum. De Palma's film has its share of twists, but isn't especially difficult to follow for anyone paying attention. There are perhaps a few too many ancilliary details introduced around the margins, but the plot unravels for the most part in fairly straightforward fashion.

If anything, that slight overcomplexity feeds nicely into the spirit of the genre that the film most closely emulates. The '70s saw the thriller genre become heavily politicised, reflecting the paranoid escalation of the Cold War and the sense that even one's own government was not to be trusted. The heroes of the time frequently found themselves questioning old loyalties and struggling to comprehend the far-reaching implications of the situations they found themselves in. Hunt starts out as the quintessential company man, loyal to a fault to his mission and his team, yet finds himself having to collaborate with an arms dealer, Max, and steal from CIA Headquarters, in the movie's exquisitely tense signature scene, the very list he was initially assigned to protect. In other words, to prove his innocence he has to do exactly that which he was wrongfully accused of doing in the first place.

That level of moral complexity is something the series abandoned immediately afterwards, which is a shame since it elevates the material so compellingly here. De Palma has great fun playing with the tropes and visual stylings of the genre, creating a rich atmosphere which adapts to the changing mood of the narrative. The first act, in Prague, is drowning in Third Man-esque shadows as Hunt finds himself alone, in constant danger and straining to make sense of a puzzle for which he seems to be missing all the crucial pieces. As he is forced to compromise his old certainties to make progress, the dominant colour scheme shifts from deep black and blues to greys and browns, emphasizing the new world of moral murkiness that the movie inhabits. As his plans start to come together for the third act climax, so too does the movie become more boldly colourful.

De Palma's love of genre cinema made him a perfect fit not only for emulating the style of old-school thrillers, but subverting it as well. Turning Jim Phelps, the only character to carry over from the TV series, into the villain was one hell of a ballsy move, not to mention an immensely controversial one at the time, but plays brilliantly into the movie's themes of shifting loyalties and political cynicism. Casting Vanessa Redgrave as arms dealer Max was similarly inspired. Redgrave turned what could have been a rote and uninteresting supporting character in the hands of a man into something far more devilish. Just as James Bond's boss, M, had recently been recast as a woman in GoldenEye (1995), the female Max reflected the growing influence of women in all areas of society, while also subverting the femme fatale trope so beloved of the genre. Max is sensual and slyly predatory, using flirtation as both a tool to achieve her ends and a mask to cover her ruthlessness. She's exactly the sort of boldly defined supporting player that later movies have so noticeably lacked, especially with Redgrave, a character actress par excellence, finding just the right level of dry wit to leverage the movie's sometimes over-serious tone.

Max's experienced, manipulative sensuality exists in stark contrast to the youth and relative sexlessness of Tom Cruise's Hunt. Even across four movies, Hunt has never found much by way of personality, but that blank slate quality works in his favour here by stripping him of much of the overblown machismo blighting so many action heroes then and now. Cruise's portrayal skews closer here to the Jeremy Renner character from Ghost Protocol: a highly competent field agent whose primary skills are in analysis rather than action. Indeed, he barely kills anyone until the movie's end. This intelligence is emphasized in one of the movie's most inspired scenes. Phelps, having returned from the dead, recounts a falsified version of how he survived his apparent assassination at the beginning of the movie. Hunt vocally accepts the story, all while mentally mapping out what really happened and confirming Phelps as the traitor. It's an audacious piece of narrative trickery in which De Palma sets dialogue and visuals against each other to simultaneously advance the plot and enrich our appreciation of Hunt's talents.

While the series would certainly go on to have its share of successes, that this early subversive streak and focus on atmosphere and plot were so thoroughly abandoned is a great loss. Mission: Impossible is not a perfect film by any means, but is a more faithful and interesting adaptation of its source material than all which would follow, while also being unafraid to subvert it to create its own big screen identity. Cinema could do with more heroes like this early Ethan Hunt, a more intellectual, even slightly nerdy version of the generic action man he would turn into for the following movie.

Cartel Land Shows Why the War on Drugs May Be Unwinnable

Released last week, Matthew Heineman's documentary Cartel Land has been roundly lauded for its harrowing, on-the-ground chronicle of the Mexican drug war. Heineman trains his lens on two vigilante groups. One is the Arizona Border Recon (ABR), a small militia-like force that patrols the Arizona/Mexico border led by veteran Tim "Nailer" Foley. The other is a much larger Michoacan vigilante organization known as the Autodefensas, led in charismatic fashion by physician Jose Manuel Mireles. Both Foley and Mireles were driven to create their groups by a sense that their respective governments weren't doing enough to confront drug cartels head on. While Foley and Mireles never meet face-to-face in the film, Heineman joins then narratively to compare and contrast these two faces of vigilantism.

Danger is palpable throughout much of Cartel Land, a testament to Heineman's embedded approach and his commitment to it. The camera is there in the thick of shootouts and drug raids south of the border, and we're given ample access to the inner workings of the Autodefensas, both good and bad. Heineman also tags along with Foley in tense and often silent stakeouts to spot border crossers who are purportedly drug mules and/or drug smugglers. (The Arizona Border Recon was originally founded to stop illegal immigrants; the Southern Poverty Law Center considers the ABR an extremist group. Make of that what you will.)

In Manohla Dargis' mixed/negative review of Cartel Land at The New York Times, she said that for all of Heineman's bravery behind the camera, he needed to exercise more of directorial point of view about the war on drugs and vigilantism. Heineman has a point of view, though I think it's quietly articulated in his comparison of the ABR and the Autodefensas, and also the overall narrative trajectory of Cartel Land. The point of view, as it seems to me, is that vigilante groups are ill-suited to address the greater challenges posed by the war on drugs, and that the war of drugs may ultimately be unwinnable (unless you're a drug cartel).

[youtube id="6JD7hPM_yxg"]

As vigilantes, Mireles and Foley seem to embody different heroic ideals in order to propel and even legitimize their groups. Mireles is like some romantic revolutionary of old, coming from the common folk and armed with a compelling personal narrative, the proper face for a populist uprising. Watch him make a speech to a crowd besieged by drug violence, see him interact with fellow members of Autodefensas--there's the air of the charismatic leader, the sort of person who attracts followers through lofty rhetoric and force of will. Mireles' second-in-command is more like Santa Claus than Che Guevara, and he doesn't have nearly the same amount of respect or command of the group. Foley, by contrast, seems taken by the Wild West idea of the cowboy and the gunslinger, even citing old-time notions of vigilantism as a way of justice and making it a way of life. (The spirit of the open frontier may be something inherent in the ideologies of most militia or paramilitary groups.) In that regard, Foley and the ABR posse are the only law left when the fellas with tin stars can't get the job done themselves.

These vigilante and revolutionary ideas are potent fuel for a movement, but they can become complicated by the compromises required to put ideas into meaningful action. That makes up the meat of Cartel Land's second half. We first watch the Autodefensas make major strides against the Knights Templar drug cartel in individual raids, but the purity of the group begins to falter as it becomes bigger and better known. Mireles becomes a media figure for the movement, and as a consequence he and his family are placed in real danger by drug cartels looking to retaliate or to strike first before the Autodefensas get to them. Power grabs within the Autodefensas, malfeasance by its members, abuses of power, and increased interest by the Nieto government in co-opting the movement mean that the Autodefensas may be destined to fail regardless of those initial good intentions.

Foley's group, by contrast, always remains small in scale, and Foley himself never becomes the face of a movement for the media. The operation is small, manageable, and seemingly incorruptible in that regard, but its size means a limited impact on the drug war. The ABR don't seem to win battles in the war on drugs. They don't even necessarily win skirmishes, for that matter. It's unclear what lasting effect they have, if they're a stone thrown in a lake making ripples, or just hail dropping in a pond and vanishing.

If governments and large institutions are ineffective or ineffectual, and if vigilante groups are either hobbled by growth or limited in impact, what solutions are there to the drug war? Similarly, if there's a constant demand for drugs, and if cartels will fill their ranks with new members and new leaders when one of their own is incarcerated and killed in order to meet that demand, is the drug war even worth fighting in the current way it's being fought?

Heineman doesn't present any solutions, but that's not a mark against the things Cartel Land does so well, which is to say its embedded journalism. Documentaries aren't always meant to answer questions. If they can, that's great, but like good philosophers, the primary role of a documentary filmmaker may be to ask the right questions, or to reframe the questions we've been asking, or to reconsider the underlying reasons we ask the questions that we ask.

Eric Kohn points out something important in his Cartel Land review at IndieWire. The film opens with Heinemen watching masked men cook meth in the nighttime. The meth cook says he knows that the drugs will harm people when they're smuggled over the border. That admission seems to acknowledge that the cartel violence in Mexico claims innocent lives and he knows it's just part of the trade. Later in Cartel Land, we hear some of these stories. There's one about babies being murdered, and one about laborers killed at a lime farm because the landowner didn't pay a cartel protection money.

"But what are we going to do?" the meth cook asks. "We come from poverty."

Good question.