Get Hard

By now, I'm sure most of you reading this are aware of the controversy surrounding Get Hard and its less than savory content. For those untrustworthy of the media and wary of overly-sensitive audiences at SXSW, I can say Get Hard is full of tasteless homophobic and racist jokes that feel completely out of touch and out of place in the contemporary climate of heightened social awareness.

Despite the uproar over the mistreatment (or perceived mistreatment, as some might argue) of the race and sexuality topics, we all know comedies are constantly attempting to push the envelope for laughs. Is this an excuse for the one-note joke that fuels the film's plot, or some of the machismo "jokes" that portray homosexuality as some disgusting counterculture? Not at all. However, without the controversy lies a comedy begging for laughs that, ultimately, it never delivers.

[youtube id="l5lojEIitNw"]

Get Hard

Director: Etan Cohen

Rating: R

Release Date: March 27, 2015

James King (Will Ferrell) is a rich businessman convicted of tax evasion and sentenced to a 10-year prison sentence despite never committing any wrongdoing. Worried that he won't survive prison, he turns to the owner of the carwash he frequents, Darnell Lewis (Kevin Hart), for help after he wrongfully assumes the latter has spent time in prison. Sensing an opportunity to make easy money, Darnell goes along with the facade, entangling James in various hijinks in an attempt to make James hard. Such scenarios include turning James' mansion into a makeshift maximum security prison, complete with James' maids and workers taking on roles as prison guards, Darnell introducing James to his gangbanger cousin and his crew, and a sexual encounter with another man at a gay bar.

The film's title, Get Hard, is enough to determine whether or not you'd enjoy this film. Does the sexual tension behind the title make you laugh at the thought of Kevin Hart attempting to help Will Ferrel "get hard"? If so, this film is for you. And really, what was to be expected of a film with such an obvious joke truly summarizing the film's tone and direction? It's one thing to be so obtuse with a film's subject matter -- it's another thing to take the premise and truly satirize it and provide conscientious, thoughtful commentary on such issues like racism, class disparity, and gay-straight relations. Instead, Get Hard goes for the obvious jokes that, to be honest, can't even be considered jokes due to their inherent lack of humor.

But again, I'm not the target audience for Get Hard, and as has been made apparent since the film's premiere at SXSW, neither was Austin's SXSW audience. That's fine, as I'm sure there will be Will Ferrell and Kevin Hart fans will flock to Get Hard and laugh at all of the sexual innuendos behind the name, gag in unison with Ferrell as he expresses his disgust over fellating another man, and chalk up all of the controversy surrounding the film to overly-sensitive types that "can't get a joke." For the rest of us, we'll just await the next Judd Apatow film for our Hollywood comedy needs.

White God

Audacity is the primary strength of White God, Hungarian director Kornél Mundruczó's political parable about a revolt of dogs against humanity, which is why the film opens with such a striking series of images: the stillness of an empty Budapest, a girl on a bike being chased by hundreds of strays. The wall of teeth and fur inspires a sense of horrified awe. It's a nightmare; something out 28 Days Later and a nature-run-amok movie (e.g., The Birds).

The film then flashes back to show how we came to that point. The technique is structurally off-putting to me whenever it's used, but Mundruczó understands the power and importance of those images. Not only are they striking (White God's marketing is built on these shots of canine revolution), they're the heart of the film. That's why as White God progressed, it felt as if the potency of that opening scene was diluted.

For that, we have the humans to blame.

[iframe id="https://www.youtube.com/embed/kIGz2kyo26U" align="center" mode="normal" autoplay="no" maxwidth="825"]

White God (Fehér isten)

Director: Kornél Mundruczó

Rating: R

Release Date: March 27, 2015

The dog that leads the eventual stray uprising is Hagen (played by two dogs, siblings, Bodie and Luke). He belongs to 13-year-old Lili (Zsofia Psotta), the daughter of divorced parents who must go stay with her father (Sandor Zsoter) for a while. In her father's building, residents who have mixed-breed dogs have to pay a tax, which leads to Hagen getting left on the side of the road to fend for himself.

The sequences with Hagen are fantastic and exhibit some of the best canine acting since Samuel Fuller's White Dog, which used the reformation of an attack dog to explore racism as a learned behavior. (Coincidentally, one of the dog handlers on White God is the daughter of the handler from White Dog.) On his first day alone, Hagen ponders the corpse of another stray, pawing at it as if trying to stir the dog awake. He fails and ruminates in a way that's all too human. Recognition dawns in his dark yet contemplative eyes, in the arch of his spine, in the angle of his ears and forepaws. Hagen's journey is a rough one, leading him from one abusive master to the next, sold and traded and devalued with each subsequent transaction.

So much can be read into Hagen's story. His first day or so is handled like a recreation of the immigrant experience, unmoored, startled by a new world, ushered into unfamiliar rules and customs. One smaller stray acts as a kind of guide for Hagen, showing him where other strays congregate and the harshness of animal control. When Hagen goes from master to master, the imagery recalls narratives of sexual slavery, sweat shop work, underground fights, and prisons. Mundruczó's done such smart work to anthropomorphize the dogs and the situations. Rather than narrow focus to a specific kind of victimization, a multitude of human miseries can be read into these situations. The dogs function as the embodiment of the downtrodden in general—the poor, the weak, the disenfranchised, the undocumented, the discarded—and the world is merciless to them.

Hagen's story is more than enough to carry White God as a film. Yet Mundruczó continually cuts back to a less engaging domestic drama and coming-of-age tale involving Lili and her father. The human stuff all seems rote rather than lived in, and marks a strange tonal shift from the raw, high-stakes political observations on Hagen's side of the story. Lili and Hagen felt more perpendicular than parallel, and almost every time White God cut back to the humans, I felt less engaged with the film. It's as if the master class held their pets back.

There's also an issue of the last third of White God, which marks another major shift in tone and focus. By then we've returned to the dog uprising shown at the beginning, and the film begins to feel less like The Birds and more like The Birds II: Land's End. The political dimension is still there and the imagery recalls, briefly, the London Riots and The Arab Spring, but it feels like the film has gone from a parable to a horror movie. Mundruczó even has a kind of slasher movie vibe in a few of the dog attacks on their human oppressors.

White God is a fascinating watch and ultimately aims high even though it's all over the place. Yet like some movies in which certain parts hit me harder than others, I'm left thinking about the film conterfactually—many "what if's" that outweigh what's there. Mainly, I wanted more of that sense of anarchy hinted in the opening scenes; more meat for the metaphor, less restraint of the beasts. The revolution will not be sentimentalized (at least not totally), but maybe it was just a little bit anesthetized.

The Boy

The Boy

Director: Craig William Macneill

Rating: N/A

Release Date: March 14, 2014 (SXSW)

Say what you will, little kids can oftentimes be the creepiest, most frightening people in the world. Their understanding (or misunderstanding) of basic social interactions is funny at times, but possesses a somewhat sinister nature. How many times have you seen children, both in media and in everyday life, do or say something that, if done by an adult, would be met with caution and concern?

The relationship between children and dark impulses has become fodder for many horror/thrillers over the years. The Boy represents a return to the trope, presented as a slow moving film that's meant to build tension and rankle unease and discomfort amongst audiences. However, the slow pacing of the film ultimately disservices the film.

Ted (Jared Breeze) is a nine-year-old boy living at a lonely highway motel owned by his father, John (David Morse), in 1989 following the departure of his mother. With his father facing depression, Ted is free to indulge his thoughts, which partially stem from the practice of luring animals into the road to be slaughtered and turned into John for a quarter. As his desire to make more money increases, so do the animals, resulting in a car accident that leaves the driver, William Colby (Rainn Wilson), stranded. The two form a bond of sorts, with both William and Ted hiding dark secrets within themselves. Ted's growing fascination with death comes to a head in the film's climax that will leave audiences stunned.

Despite a climactic ending, The Boy takes far too long for the payoff, which may disappoint viewers. Furthermore, Ted's evolution in his creepiness can make audiences uncomfortable with the levels of creepiness on display. Fans of psychological thrillers will love where writer/director Craig William Macneill takes the film, but the best of praise will be held for Breeze and his depiction of Ted. His ability to balance and hide Ted's sinister and devious thoughts without being a cartoon-like caricature of the trope.

As a rumored first part in a trilogy, some excuses could be made for some characterization/pacing that plagued the film. The payoff could mean a tighter, more focused sequel, but as it currently stands, works against the film on its own. The Boy is a very solid debut by Macneill and will attract a small cult following to be appreciated by horror cinephiles.

Fresno

Fresno

Director: Jamie Babbit

Rating: N/A

Release Date: March 14, 2015 (SXSW)

Fresno features a stellar cast of Natasha Lyonne (Orange is the New Black), Judy Greer (Archer), Aubrey Plaza (Parks and Recreation), Fred Armisen (Portlandia), and more that allures comedy lovers into not missing it. And with a plot that features Lyonne as an optimistic presence in her recovering sex addict and cynical sister played by Greer, the formula for a solid indie comedy is all but assured, right?

Read on and find out.

Shannon (Greer) is a recovering sex addict living and working with her younger sister, Martha (Lyonne), who takes her job as a hotel maid very seriously and is doing everything in her power to assure Shannon's successful recovery. However, after Shannon's relapse with a guest at the hotel ends with his death, the two decide to dispose of the body by bringing it to a pet cemetery for incineration. However, when the cemetery owners, played by Armisen and Fargo's Allison Tolman, blackmail them for $25,000, Shannon and Martha must come up with the money quickly in outlandish ways.

Fresno subverts the typical formula by making Shannon almost completely unlikeable save for her quick wit and other quirks, making her an anti-hero of sorts. It's an interesting take on the plot that allows Greer to play up the ungrateful, unrepentant type to let her comedy shine. However, the script and writing for the film is very flat and one-dimensional, despite some funny scenes set up, like robbing a sex shop and a rap-themed Bar Mitzvah.

In short, Fresno isn't very funny, save for some small exceptions. It's a shame, too, because the cast is made up of some really hilarious actors, yet they weren't given the proper material to truly show off their talents. In a nutshell, Fresno feels like a vehicle for Greer and Lyonne that unfortunately suffers from a flat or two.

Champs

With this generation's new "megafight" between Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather coming in May, boxing is at a pivotal point in time where the future of the sport can return to the same heights it once experienced many years ago. Champs is a documentary that not only revisits the '90s heights of the sport in which heavyweight champions like Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, and Bernard Hopkins were three of the sport's most storied fighters... for both good and bad reasons.

Rather than follow the typical fare of most documentaries, writer/director Bert Marcus frames the documentary around the three boxers to examine the pratfalls of financial success for athletes who may not be the best equipped to handle the limelight, racism and poverty that pervaded the sport, and the very fact that boxing still goes unregulated with no true safety parameters set for its athletes. However, was Marcus successful in crafting a documentary that aims for bigger goals? Read on and find out.

[youtube id="yF1qq3fEYAM"]

Champs

Director: Bert Marcus

Rating: N/A

Release Date: March 13, 2015 (in theaters, On Demand, and iTunes)

As previously stated, Champs contextualizes the career trajectories of Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, and Bernard Hopkins with the socioeconomic issues that plagued them. While backgrounds of each boxer are examined in Champs, they aren't the focal point, but instead reference points to support the film's main goal of illustrating how the sport helped them escape the trouble they grew up with, just to face some of the same issues within their chosen fields.

Marcus focuses on this irony, but rather than be condescending, he illuminates the problems and issues that were present in hopes of bringing awareness. Furthermore, he compares the problems that plagued boxers with the same issues that are present right now in regards to boxer safety, sport regulation, etc. By taking this route for the film, Champs becomes not just a documentary set on a specific time, but one that compares and contrasts the past with the present through a sport that was once the country's largest.

The increased focus in direction and tonality is matched by feature film-levels of production quality, heightening the bar for the typical sports documentary, let alone documentaries in general. The documentary is also helped by direct assistance from Tyson, whom also produced and helped get in touch with some of the insiders interviewed. The way the film is presented, the majority of its audience will predictably come from boxing fans, but will also benefit those interested in modern social issues, which is a well-balanced product for a documentary that transcends the typical sports doc.

While I'm unfamiliar with Marcus' previous documentaries, Teenage Paparazzo and How to Make Money Selling Drugs, I'm confident if the rest of his filmography, both past and future, is anything like Champs, audiences will be drawn to them. His focus on telling captivating narrative to bring positive change to social issues matched with a high level of production quality is certainly Marcus' strongest skill with Champs, and even those unfamiliar with boxing and/or the modern climate of American sociology will be drawn to it.

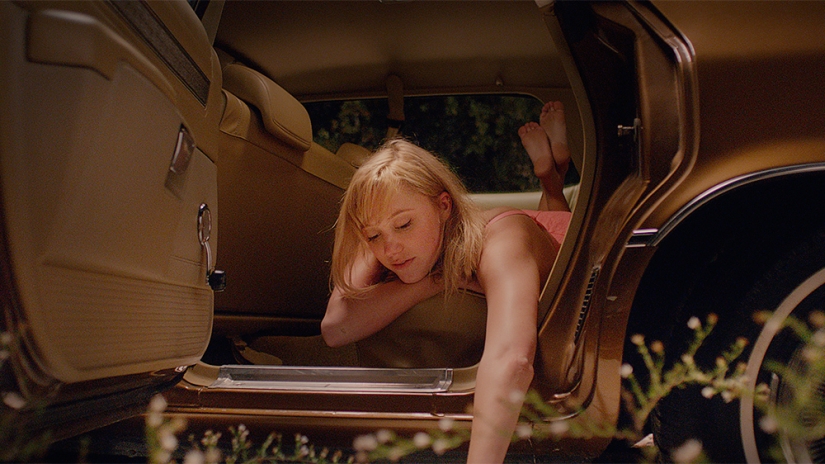

[Review] It Follows

It Follows belongs in the pantheon of great suburban horror films like Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street. It's an impeccably crafted movie that haunts as much as it unnerves. What lingers isn't just the paranoia established from the outset or the constant sense that our heroes' lives are in danger, but something far more thoughtful.

Writer/director David Robert Mitchell uses 1980s genre tropes to examine teenagers as the cusp of adulthood. Many of the characters are obsessed with becoming adults or at least appearing mature, and yet they're also afraid to leave the comforts of youth and suburbia. To dig deeper into this material, Mitchell does advanced math with one of the most simple horror movie equations: "sex = death".

[youtube id="9tyMi1Hn32I"]

It Follows

Director: David Robert Mitchell

Rating: R

Release Date: March 13, 2015

Jay (Maika Monroe) hooks up with a guy named Hugh (Jake Weary), which wasn't such a good idea since he's the latest link in a chain of doomed sex partners. After having sex, the most recent partner becomes stalked by a supernatural presence that shambles mutely forward. Think a zombie or Michael Myers from Halloween. If the presence catches up with you, you die, and the previous sex partner is stalked next. All you can do is pass it on; sex is a kind of transmittable death sentence.

It sounds silly on the surface, and this sort of set-up might lead to exploitation territory in other hands, but Mitchell focuses on the characters and how the immanent threat of dying enters their sheltered lives. Like Jennifer Kent's The Babadook, It Follows is concerned with emotional stakes rather than just cheap scares, which is thanks to both the screenplay and the cast. By getting the audience to invest in this group of teenage friends and care about Jay's well-being, the horror is more palpable.

In slasher movies, sex usually signified a sin that needs to be punished or the horrible repercussions of pleasure, but there's more to sex in It Follows. Sex is both a rite of passage into adulthood and a kind of memento mori. In this film, "sex = death" is not a puritanical equation about the virtues or pragmatism of teenage virginity, but rather an acknowledgment about the inevitability of both sex and death in everyone's lives. Sex, like death and like the presence that's after Jay, is an unstoppable force.

All the rich metaphorical material would be mere garnish if Mitchell hadn't made a film that's so well put together. It Follows is shot with care, augmented by its original synthesizer score (a la classic John Carpenter) and the menacing sound design. In the opening shot of the film, we're given an extended take from a fixed spot on the street of a suburban neighborhood, panning to catch someone helpless and possibly insane. Something's not right in the world we've entered, which defies being pinned to a specific era, and we never exit this timeless, dreamlike state. That opening shot creates a space to deal with the idea of teenagehood, and it also lets the audience know that the adults can't help their children anymore. This confrontation with death is something their kids have to handle on their own.

So many of the images in It Follows are beautiful to look at given the way cinematographer Mike Gioulakis plays with color, movement, and negative space to emphasize the underlying emotions of each scene. Clayton Perry, Christian Dwiggins, and Lauren Robinson of the sound department also deserve high praise, foregrounding the dread even before the film's first shot. It Follows is a great reminder of how effective the most basic formal elements of a movie can be when every choice has a clear sense of purpose.

A bunch of horror and science fiction films of the last decade have tried to get by as successful pastiche and nothing more, as if recreating the past is sufficient. It's usually not. Most people can restate what's already been said, but what gives a work a life of its own is when someone says something original or reconsiders what's been said from different angles. It Follows is brimming with that sense of vitality, which makes everything it says about dying surprisingly potent.

[Review] My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn

"Art is hard." That's the underlying thesis of most documentaries about making movies. The truism is present throughout My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, a one-hour documentary shot by Refn's wife, Liv Corfixen, while he was making Only God Forgives. Refn seems perpetually distraught as he's writing and directing his follow-up to Drive. He spends multiple scenes in his lavish 42nd-floor Bangkok hotel room sulking on the couch, depressed in bed, or pensively looking out the window at the world below. What's on screen is just a snippet of the woe. Cofixen complains behind the camera that Refn doesn't allow her to film when a major crisis occurs.

There seem to be two other threads running through the documentary that are intertwined with the idea that art is hard: "success is damning" and "failure is inevitable." My Life Directed by Nicolas Windin Refn is about how artists interpret failure and the sense that they're failing. How fascinating you find the film depends on how closely you follow Refn's work and your patience for the banal.

[iframe id="https://www.youtube.com/embed/6Rz9SAZQrH0" align="center" mode="normal" autoplay="no" maxwidth="825"]

My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn

Director: Liv Corfixen

Rating: PG-13

Release Date: February 27, 2015

My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn is only kind-of about the making of Only God Forgives. The primary focus is Refn's artistic struggle in mundane settings—hotel rooms, cabs, before screenings—rather than on set. The film opens with Refn so anxious about making a new movie that he asks his hero and friend, legendary cult filmmaker Alejandro Jodorwosky, to do a tarot card reading for him. Maybe the narrative symbolism of the cards will ease Refn's superstitious mind. Candor thrives in these unassuming places. Refn's no longer forced to play leader for a crew and can let his guard down, or at least maintain a haggard-yet-guarded front for Corfixen's camera. When a camera's involved, intimate disclosures only go so far, even if you're married.

Ryan Gosling appears in a few of these off-set sequences. The eye gravitates toward him—star power in action. These scenes with Gosling have a sly, jokey, almost mockumentary feel, which makes them especially entertaining. While Refn explains his ideas about the similarities between violence and sex, Gosling smirks at the camera like Jim from The Office. I wouldn't mind a mini-series starring Refn and Gosling together on the road, sort of like Michael Winterbottom's The Trip with Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon.

Despite a few enjoyable scenes, My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn is only semi-interesting. Even at just an hour long, the material is thin and superficial, less a crafted non-fiction narrative and more a home movie. At worst, it's a glorified featurette for the Only God Forgives Blu-ray. Even fans of Refn might shrug the documentary off. If you aren't familiar with Refn's work or Only God Forgives, you might wonder why that man in a beautiful hotel is so depressed.

Refn comes across too worried and too self-absorbed for the film to be self-congratulatory, and so the documentary avoids becoming a complete vanity project. Yet there's a sense of self-importance that's unwarranted. Only God Forgives may have been low-budget, but apart from the usual on-set challenges, nothing seemed especially noteworthy. Sure, it's Refn's big critical and commercial failure, but he bounces back from it unscathed.

Toward the end, Refn complains that he's wasted six months of his family's life. Consider the Herculean struggles in other documentaries about making movies, such asThe Burden of Dreams, Hearts of Darkness, or Lost in La Mancha. By comparison, Refn's problems, while legitimate and disheartening, seem like temporary frustrations rather than existential struggles for authenticity or the difference between subsistence and going hungry. As the documentary shows, Refn's problems are nothing that a good sulk won't fix.

[Review] All the Wilderness

Indie films in which teenagers have to cope with the death of a close family member or loved one tend to be dark, moody films contrasting the loved one's death with the protagonist's "birth" (or "rebirth"). They're somewhat formulaic and predictable, with adventurous films utilizing the concept into a genre film. Nevertheless, it's hard to argue against how influential the impact of a death has on a teenager at a time when nearly everything in the world will have some bearing on creating who said teenager will become. While All the Wilderness does utilize the concept, the film separates itself from the pack with an entrancing soundtrack, perfect casting in Kodi Smit-McPhee, and cinematography that lends itself well to both Portland's urban and rural landscape.

[youtube id="FjuDhvPiaVg"]

All the Wilderness

Director: Michael Johnson

Rating: N/A

Release Date: February 20, 2015

Still reeling from his Dad's suicide, James (Smit-McPhee) has found himself fascinated with nature and death, occupying his time sketching illustrations of dead insects and animals into a notebook and telling another kid that he knows when he'll die. Worried about her son's development in the wake of the death, James' Mom (Virginia Madsen) makes him visit a shrink (Danny DeVito) weekly, and it's at his office that James meets Val (Isabelle Fuhrman), an alluring girl whom he is immediately drawn to. During one adventurous night in which James explores the "wilderness," he meets Harmon (Evan Ross), a street punk that immediately brings James into his circle. It's through Harmon and Val that James begins to find a new sense of self and identity

Smit-McPhee shines in All the Wilderness, living up to the accolades the actor has garnered in his already storied, but young career. In the wrong hands, James would have been a whiny brat; in Smit-McPhee's hands, rather, he's a multi-layered character inquisitive of his place in the world. The characterization is also thanks to the sound writing and direction from the debuting Michael Johnson. Alongside cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra, Johnson's story and vision examines all sense of the word "wilderness" by comparing and contrasting the vast woods near James' home to the squatter warehouse where Harmon lives and the wild, rebellious night life James is introduced to with the reserved, introverted life James spent prior to meeting Harmon. Accolades must also be shared for the film's soundtrack, which features Sonic Youth, Elliot Smith, and songs from Jonsi and Alex of Sigur Ros; if there were ever a soundtrack that was capable of capturing teenage melodrama that can also capture the atmosphere of a wild forest or city setting, this would be it.

All the Wilderness will appeal to indie film darlings that can't get enough of coming-of-age films (like myself). As mentioned earlier, Smit-McPhee continues to show growth and talent at a young age, and it's only a matter of time before he finds stardom (outside of his recent casting as Nightcrawler in the upcoming X-Men: Apocalypse). Writer/director Michael Johnson also shows promise with a strong debut.