Nintendo confirmed at a press conference this week that their next console, codenamed the ‘NX’, was on the way, with more details set to be revealed in 2016. That the company is working on the Wii U’s successor is hardly a surprise, having been hinted at much several times over, though the fact this news attracted so much attention despite only being revealed as a way of quashing any speculation of Nintendo quitting the dedicated hardware market – having been announced at the same time as the company’s plan to licence its characters out for mobile game development – shows how important a place the company occupies in gaming culture even with the abject failure of their most recent home console.

The Wii U has yet to cross the 10 million global sales mark, having been available to buy since Christmas 2012. By contrast, the company’s previous low watermark for home console sales, the GameCube, sold 22 million units between 2001 and its discontinuation in 2007, while the Xbox One and Playstation 4 have already outsold the U despite launching a year later. Sales of the 3DS have been more stable, shifting a creditable 50m units as of December last year. This pales in comparison to its predecessor, the DS, however, which sold just over 150m across its lifespan and is the top-selling handheld of all time.

The news of Nintendo finally, some would say inevitably, caving into the pressure to move into the mobile arena sent the price of their stock soaring by 29%, yet this represents something of a dilemma for its traditional audience. If the company’s mobile ventures prove successful, as seems likely to be the case – their partners, DeNA, are hugely experienced and successful in the mobile gaming field, while Nintendo’s catalogue of mascots have the kind of global recognition and appreciation which should guarantee a high level of trust and curiosity out of the gate -and they continue to struggle to assert themselves in a dedicate games hardware market where Sony and Microsoft are seen as more contemporary and exciting options by most so-called ‘core’ gamers, what reason is there for Nintendo to continue resisting the urge to dedicate most or all of its resources to mobile game development?

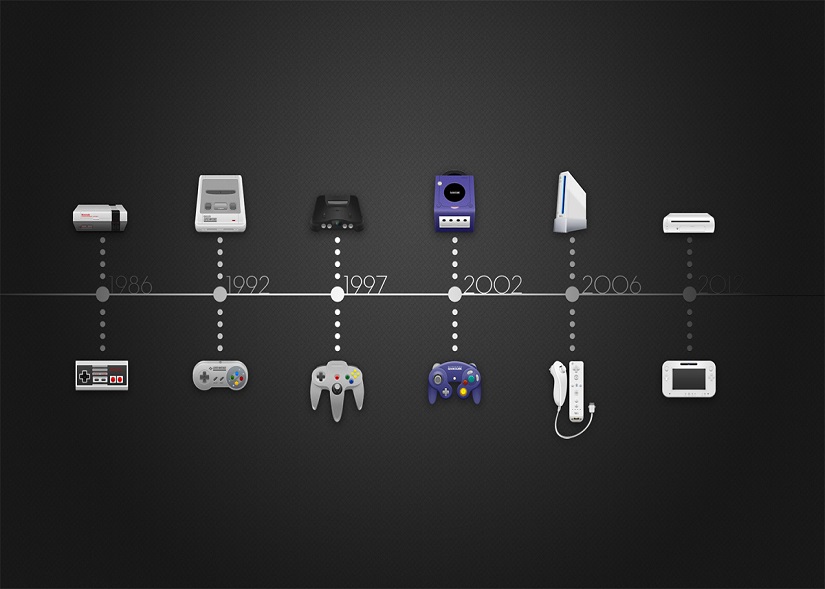

The fact is that, regardless of its recent difficulties, the gaming hardware market would be a very different and less exciting place without Nintendo. After the video game crash in 1983, the company almost single-handedly revived the market with the Nintendo Entertainment System with a business model which, through licencing, guaranteed customers a certain level of build quality in their games. Its successor, the SNES, solidified Nintendo’s place as the dominant force in the market, despite growing competition from SEGA. Their next console, the N64, would lose considerable ground to Sony’s newcomer, the PlayStation, yet despite sticking with outdated cartridge technology, the controller’s use of an analogue stick revolutionised the way games controlled in a three-dimensional space. The Gamecube saw Nintendo’s stock fall yet further, with Microsoft entering the market with the original XBox, but the system’s Wavebird controller revision was the first to offer a wireless connection to its console.

Little was expected of Nintendo’s follow-up system, yet the Wii’s unusual name and innovative yet simple motion controller caught the public imagination and quickly became a bonefide phenomenon. Unfortunately, the console’s unreliable motion-sensing technology, combined with outdated hardware (offering only standard definition output against the XBox 360 and PS3’s HD) and a combination of third parties flooding the market with low-quality games to get in on the rush while Nintendo struggling to fill gaps in their release schedule, meant the brand quickly soured for much of the company’s long-term fanbase.

This led to the Wii U, a console mired in confusion and compromise from its unveiling, at once offering more traditional controls to appease disgruntled fans while continuing to confusingly utilise the Wii name, require a bafflingly large number of controller types (gamepad, wii remode, classic controller, etc) and centre around a touchscreen which was often inconvenient to use and has offered little in gameplay terms beyond an always-on map or inventory screen, plus the limited appeal of being able to continue to play even while not using the television.

The PS4’s outstanding sales, undeterred even by a widely acknowledged dearth of worthwhile games in its catalogue, shows how important strong marketing is to a console’s success. Despite its past innovations and the consistently high quality of its games, Nintendo is perceived by much of the gaming market as staid, childish and outdated, heavily reliant on gimmicks where Sony and Microsoft have pushed state-of-the-art (for consoles, anyway) technology and online infrastructure. They are seen to have little to offer anyone without an existing appreciation for a small number of popular franchises, a number increasingly limited to spin-offs of the Mario and Zelda games. Major third-party series such as Call Of Duty, FIFA and Assassin’s Creed have all floundered on the Wii U, with recent iterations missing from the console altogether. The Grand Theft Auto series, meanwhile, has never graced a Nintendo home console.

If Nintendo are to succeed, it would seem they need to stumble upon another zeitgeist-defining innovation in the same vein as the Wii’s motion controls while simultaneously offering a level of technological power at least in the same ballpark as its competitors. That need to find the next big innovation is itself somewhat problematic, though, not least because of the unlikelihood of even a company as inventive as Nintendo making the proverbial lightning strike twice, but also because the company’s current association with gimmickery means offering anything but a standard dual-analogue controller is likely to be greeted with immediate suspicion.