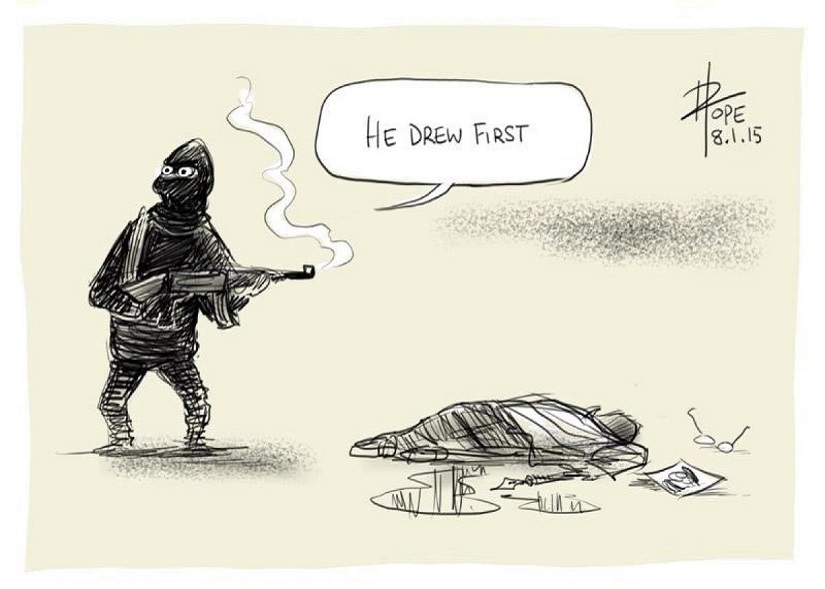

It’s been just over two weeks since the horrific attacks on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris, long enough for the initial surges of sadness and anger to die down and be replaced by something resembling more considered reflection. There’s been considerable rumination on what the attacks mean for free speech and artistic expression, including by Ruby Hornet’s own Hubert Vigilla, questions which eventually spawned a mini-debate of their own over whether Hebdo’s representation of Muslims could be classed as racist. Elsewhere, many commentators haved raised the West’s perceived responsibility in helping cultivate radicalisation as a result of mismanaged military incursions into the Middle East, notably the 2003 Iraq War.

More recently though, in addition to questions about why the Hebdo murders attracted so much more media attention than the slaughter of two thousand people by Boko Haram in Nigeria, another debate seems to have been gaining traction. This argues that, by the media so consistently using the attacks to raise questions about the West’s actions elsewhere or to questions about the morality of the Hebdo covers at the root of the attacks, a process is taking place whereby the attackers themselves are having the responsibility for the murders lifted from their hands and transplanted into the laps of the culture and society which was attacked.

Despite being linked to recent events, the notion of the media being apologists for terrorist atrocities is not new. Its advocates have recently been linking to this blog post by (now deceased) political theorist Norman Geras, written in response to the London bombings in July 2005, a period when the Iraq War was still in its infancy and the world was still trying to make sense of the political and military landscape created in the aftermath of 9/11.

Geras argues that the pervasive culture in response to the bombings has been one of ‘I told you so’, where every mention of the tragedy of the bombings has to be suffixed with a reminder that it was our actions in the Middle East which must acknowledged as responsible for bringing these horrors to our doorstep. He goes on to mirror such reactions to the shaming of a rape victim rather than the rapist. In his words:

Bob, an occasional but serial rapist, is drawn to women dressed in some particular way. One morning Elaine dresses in that particular way and she crosses Bob’s path in circumstances he judges not too risky. He rapes her. Elaine’s mode of dress is part of the causal chain which leads to her rape. But she is not at all to blame for being raped.

The fact that something someone else does contributes causally to a crime or atrocity, doesn’t show that they, as well as the direct agent(s), are morally responsible for that crime or atrocity, if what they have contributed causally is not itself wrong and doesn’t serve to justify it. Furthemore, even when what someone else has contributed causally to the occurrence of the criminal or atrocious act is wrong, this won’t necessarily show they bear any of the blame for it.

Others have argued that by using the terrorists’ stated motives – blasphemy against the Prophet Muhamed – as a basis for condemning our own behaviour, we are perpetuating what this article by Yasmin Baruchi calls an ‘us versus them’ narrative, playing into the hands of extremist clerics using division as a tool of radicalisation. By debating whether Charlie Hebdo is racist against Muslims and accepting as a starting point that the cover in question was an act of blasphemy, Baruchi argues that rather than healing wounds, it has opened new ones by encouraging the perception that Muslims are mistreated, targeted and disrespected in Western society.

As author Jeremy Duns so succinctly tweeted on January 10th of this year:

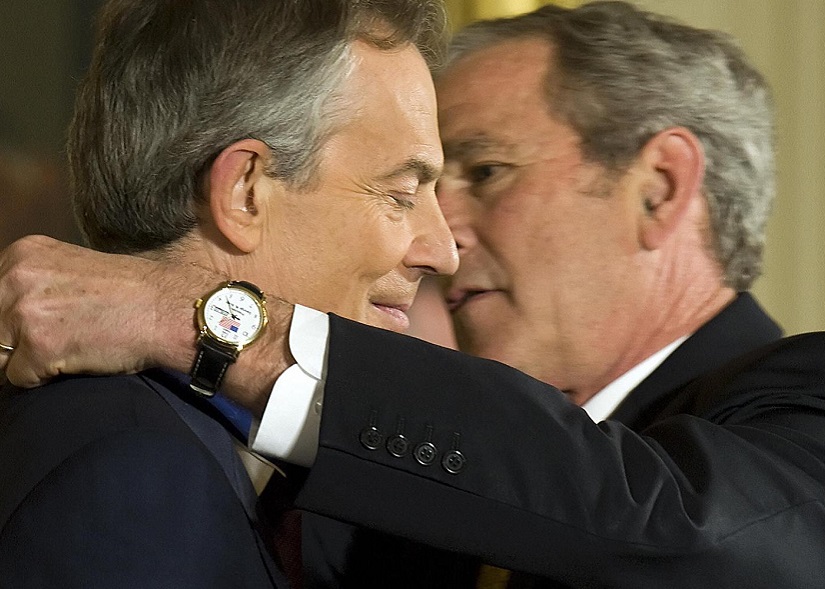

Any fascist can murder cartoonists and simply say they were motivated by Abu Ghraib and somehow Bush and Blair share the blame. Brilliant.

There’s a great deal in these arguments I disagree with. As was my response to Mr. Duns at the time, the danger of adopting these attitudes is that it risks encouraging the view that the West is nothing but a blameless victim, existing outside a cause-and-effect universe where events such as the occupation of a sovereign nation and power vacuum left behind can be given a free pass for possible consequences further down the line – even if those consequences involve our society subsequently becoming victims.

That, too, is where my issue with Mr. Geras’ rape analogy arises. In this instance, the Charlie Hebdo attacks were undeniably a horrific attack on our culture and our society, yet Geras’ metaphor (albeit for a different tragedy) neglects to take into account that such attacks are not isolated incidents but the latest in a long line, as tragic and shameful as the loss of life always is, but also inexorably linked to one another. Before these attacks, there were the myriad atrocities of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as drone warfare in Pakistan. Before that, there was 9/11. Before that, there was the first Gulf War, and so on. This chain goes back a very, very long way, leaving scars inflicted by both sides as far back as history records. A more appropriate metaphor might be gang warfare, where both sides alternate between being the victims and perpetrators of violence.

Geras, Baruchi and Duns are correct in calling out commentators who use these tragedies as a means of gaining backdoor support for their political views in much the same way that extremist clerics do to radicalise their followers. Just as there must be a time for self-reflection, it is equally important to honour the victims with a period of apolitical mourning, when we acknowledge the sadness of more needless death without turning it into propaganda. Considering the long and violent history of conflict between Western and Islamic cultures and ideologies, the media’s readiness to lay the threat of terrorism solely at the door of the Iraq War is undeniably short-sighted: as Salman Rushdie would attest, Islamic extremism is hardly an invention of the 21st century.

I am, however, far from convinced that to make such a case involves morally absolving the Hebdo killers of the entirety of the blame for their crimes. Myopic and politically motivated, perhaps, but reflecting on how a murderer’s background might have led to their crimes is not the same as letting them go free or diminishing their sentence. It is searching for clues as to what led an atrocity to occur and what it might be possible to do to stop it happening again. Perhaps, in the case of preventing terrorism, that means recognising mistakes we might have made in the past. Perhaps it means accepting that sometimes evil exists simply because it can, using outside circumstances as an excuse to justify itself. Humanity’s need to find order in chaos can often be misguided or misappropriated, but if by hook or by crook it ends with one fewer instance of bloodshed on either side, I’d say it’s worth persevering with.